Global efforts to achieve equality for women at the top of the legal profession are struggling to get results. Melanie Newman finds out what is going wrong – and what is working

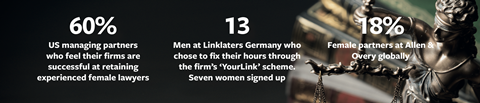

Today, many, if not most, of the large international law firms carry statements on their websites proclaiming their commitment to equality and diversity. But the figures tell their own story: just 18% of Allen & Overy’s global partners are women; for Linklaters and Clifford Chance, the figure is 20%. They are not atypical.

Many firms also have goals and strategies aimed at increasing their numbers of female partners. But it is easier said than done, and if evidence from the US applies to other jurisdictions, even those with policies have no reason to be complacent. A recent survey of lawyers at the 500 largest US law firms found a large ‘perception gap’ between managing partners and their female staff about their firms’ efforts to retain and promote experienced women.

The 2019 Walking Out the Door report by the American Bar Association (ABA) and legal consultancy ALM Intelligence found 60% of managing partners felt their firm had ‘been successful at retaining experienced women lawyers’. Three-quarters of male lawyers agreed with the statement; less than half of female lawyers did.

Replies to other questions also strongly suggested that women do not view their firms’ efforts to achieve sex equality in anything like as positive a light as the firms’ leaders and male colleagues.

What explains this perception gap? ‘It may be that managing partners and senior men are unaware of the actual statistics,’ the report suggests. An alternative – and perhaps more likely –explanation is that managing partners and senior male lawyers have different expectations, or criteria for assessing their firms’ success in retaining and promoting female lawyers.

The report also looked at law firm initiatives aimed at increasing numbers of senior female lawyers and found wide variation in their management, funding and formality. Women’s views of these policies’ effectiveness in improving career progression and retention also varied.

At least three-quarters of women felt working from home, clear consistent criteria for promotion to equity partner, and a formal part-time policy for partners were effective policies. By contrast, just 42% felt the same about sexual harassment training and implementation of the Mansfield Rule. The latter, when used, requires at least 30% of candidates whom US law firms select for significant leadership roles to be women, LGBTQ+ or BAME.

‘On-ramping’ programmes, which are designed to help women re-enter the law after a career break, were even less well regarded, with only 37% of those surveyed perceiving them as effective.

‘Simply putting policies into place and giving lip service to the goal of diversity appears to have little impact,’ the report concludes. ‘Enacting policies is a basic first step, but it is not enough. And while large firms have developed policies designed to address the gender gap, there is significant variation in the nature of these policies, how well they work in practice, and whether the policies are implemented consistently and equitably over time.’

Stephanie Scharf of Chicago firm Scharf Banks Marmor, one of the report’s authors, told the Gazette firms should not expect a single ‘silver bullet’ policy to deal with the problem of female attrition.

‘Each firm has to look at its specific culture and needs, devise a strategy on those bases for advancing women into senior roles, and use the policies that best fit their strategy,’ she says.

However, she adds that many US firms are poor at accommodating needs outside the workplace and lack policies for flexible and part-time working.

Düsseldorf-based Dace Luters-Thümmel, secretary general of the European Women Lawyers Association (EWLA) and a sole practitioner with expertise in EU law, recalls that, a decade ago in conservative parts of Germany, female lawyers returning to work after maternity breaks were given secretarial jobs or forced to take part-time roles.

‘You could not convince anybody that you really wanted to work full-time, as nobody could imagine it,’ she says.

Times have changed, she admits, driven partly by Germany’s aging demographic. Amid shrinking numbers of young lawyers, firms cannot afford to exclude female talent.

‘But who knows what would happen if the labour market were to change again?’ she adds. Luters-Thümmel is not convinced that men’s attitudes have changed dramatically. Her solution was to set up her own firm and she believes this may continue to be the best option for some women.

One firm in Germany that has tried to accommodate its lawyers’ needs outside the office is Linklaters. Two years ago it introduced YourLink, which enables all full-time lawyers to fix their hours – to an average of 40 hours per week – and gives them flexibility over when to work, in return for a substantial pay cut. Once staff have completed their agreed hours for the day, they are not expected to check their emails; colleagues are discouraged from contacting them and are required to fill in where necessary.

On paper, it sounds like a policy that would be welcomed by mothers of young children. At least one of the scheme’s female members would have left the firm to go in-house had it not been on offer. But when the Gazette asked Linklaters Germany for more details about take-up, the answer was unexpected: it has proved more popular with men than women.

‘We currently have 20 lawyers – seven female, 13 male – who are working within the YourLink model,’ says Simone Heil, a press spokeswoman for the firm. Participants are using their additional free time to play sports and pursue other interests, as well as look after children. Just three of the scheme’s participants are working part-time. Twelve lawyers have swapped into the scheme while eight joined it on starting at the firm.

YourLink may be proving a useful recruitment tool, but whether it will address Linklaters’ dearth of female partners in Germany is moot. According to the firm’s 2019 worldwide diversity report, just 15% of partners in the firm’s five German offices are women. YourLink participants are also ineligible to become partners at the firm, although it is possible for them to become managing associates or counsel.

‘Partners are required to develop client relationships, spot business opportunities, and anticipate and respond to clients’ needs,’ Heil says. ‘This is only possible with an extremely flexible and entrepreneurial approach, which needs to be pursued before becoming a partner. Hence, it is not realistic to move directly from the YourLink model to the partnership.’

However, she adds that it is possible to work in YourLink for a while, switch to the classic track and then become a partner.

Moving the numbers

Ten recommendations from Walking Out The Door: The Facts, Figures, and Future of Experienced Women Lawyers in Private Practice by Roberta D Liebenberg and Stephanie A Scharf

1. Develop a strategy, and set targets and a timeline for what you want to achieve.

2. Measure and track the status of metrics such as attrition, promotion, work assignments, compensation and bonuses.

3. When a senior female lawyer leaves, conduct an exit interview. Collate the findings over time.

4. Senior partners should be assigned an initiative or area of improvement for which they are personally responsible and must be held accountable if measurable progress is not made.

5. Ensure that there is a critical mass of female partners on key firm committees, particularly those that make decisions concerning the advancement of lawyers to partner and equity partner positions and appointments to leadership roles.

6. Firms should consider adopting the Mansfield Rule, which sets an aspirational goal of having at least 30% of candidates for significant leadership roles be women, LGBTQ+ or BAME.

7. Assess the impact of your firm’s policies and practices on female lawyers.

8. Implement implicit bias and sexual harassment training for all partners.

9. Increase lateral hiring of female partners.

10. Provide assistance and support to lawyers with family obligations, such as childcare programmes, concierge services and flexible working, to make a work-life balance more achievable.

Across the border in Vienna, Austria, Dorda shows how much further flexible working can go. Francine Brogyányi is the part-time managing partner of the firm, which in 2016 made ‘female empowerment’ a division alongside human resources, finance and marketing.

‘We had seen a lot of good women leaving before they became really senior,’ she says. ‘It was difficult to find out exactly why but the feeling we got was that they didn’t really believe they could have a family and be a lawyer or partner.’ There were two aspects to that, she adds: ‘Working hours and not enough role models.’

The firm’s answer was to allow all its lawyers to reduce their output, defined as billable hours, by up to half for any reason and to work from home some of the time. This ‘of course’ leads to a fall in hours worked. Hours worked are also more flexible. Echoing Linklaters’ experience, more men than women took up this offer, but it has, nevertheless, had an impact on both recruitment and retention of women: half of the firm’s senior associates are women, up from 25% before the change.

The move has yet to impact partner statistics, however. Brogyányi is the only female partner out of 20, but she believes improvements are only a matter of time. ‘Three of the partners are part-timers. We are showing the women coming up that it is possible to reach partnership and not work 100% at the firm.’

In this time of crisis – Austria currently has more than 2,000 coronavirus cases and travel restrictions in place, so most lawyers have been forced to work from home – the investment is paying off, Brogyányi believes. ‘We are already used to people being unavailable at certain times. I really do think it’s made the transition easier.’

Dorda also runs networking, training and mentorship programmes. The latter involves women who are leaders in their fields outside private practice giving talks and tips, as well as internal mentoring.

Katharina Miller, the president of EWLA and founding partner of boutique Madrid firm 3C Compliance, is keen to emphasise the role the four Spanish women lawyers’ associations have played in raising awareness and creating mentorship networks. For example, the Barcelona bar association – which has changed its name to Abogacía, the female gendered version of the word ‘lawyer’ in Spanish – introduced an equality certification system in 2019, based on law firms’ policies and implementation.

‘Half of the articles in the bar magazine are written by women,’ Miller adds. ‘The bar also offers a course for women lawyer leaders and organises at least one event a year on gender equality. Other bar associations are now following this example.’

The Madrid bar started a sex equality survey last year and dedicated an entire issue of its magazine to the subject.

Still, there is a long way to go. ‘I can feel more awareness between women lawyers but I cannot say the same for our male colleagues,’ Miller says. ‘I think they feel threatened and don’t understand what “our problem” is now that there are so many women at universities and in the legal professions.’

Italy is home to some examples of good practice as well. Portolano Cavallo has adopted a head-to-toe approach to sex equality, both internally and with clients. More than half its lawyers are women and so are 44% of its partners, while seven of its 13 practice areas are headed by female lawyers.

Partner Antonia Verna says the firm has always supported women’s professional growth ‘in a spontaneous way’ without top-down injunctions.

‘We pay maternity leave for three months as standard, we allow women unpaid maternity leave without any adverse effects on their careers, we incentivise part-time and home working, and we provide all our associates, including trainees, with the tools to work from home,’ she says. In addition, partner meetings are arranged around the availability of part-timers, and meetings and conference calls are avoided in the late afternoon when children are coming home from school.

‘This has never affected our relationships with the clients, who appreciate our respect for work-life balance,’ Verna says. Portolano also operates a company-wide collective bargaining agreement [of a type] aimed at improving conditions for law firms nationally.

The success of a policy in a country may vary with practice area, with some disciplines requiring particular measures. Katherine Bueti is a founding senior partner at criminal law firm Bueti Wasyliw Wiebe in Winnipeg, Canada, and immediate past-president of the Law Society of Manitoba. She tells the Gazette attrition of women happens in her field at an earlier stage than in civil practices.

‘Women start to drop out after seven years in general, but in criminal law it’s a lot sooner,’ she says. There is only a handful of female defence lawyers with 15 years’ experience, she adds. ‘Even those with 10 years’ experience are hard to find.’

As in the UK, legal aid rates for defence work in Canada are woeful. ‘There has been no rate increase in Manitoba for a decade,’ Bueti says. ‘There is no work-life balance. The working hours are obscene.’

The work also takes its toll, she adds, and while prosecutors, witnesses and jurors are offered mental health counselling, ‘the defence lawyers don’t get it’. These issues affect both men and women but in Bueti’s experience many of the female lawyers struggle to cope if they are or become mothers. ‘The men in these positions often have a spouse at home, whereas a lot of the women don’t – a high volume of the junior lawyers are single mothers,’ Bueti says. ‘It is incredibly taxing for them.’

In India, there are far fewer senior women in litigation than in non-contentious work. Zia Mody, managing partner of AZB & Partners in Mumbai, has been outspoken about the difficulties and mental strain on female counsel, who have to perform before predominantly male audiences and judges.

The solution has to be bespoke, she says: ‘There is no one policy that can make it work for all. This is when the leadership has to step in and listen. And HR has to be flexible in problem-solving to retain this incredible pool of talent.’

Mentoring is also important, she adds. However, she points out that most mentors are men, because there are few women in top positions and they tend not to initiate conversations about flexibility. At the same time, women are sometimes reluctant to ask for what they need. ‘Women must understand that if you don’t ask, you don’t get,’ Mody adds.

'Women are everywhere over-mentored and under-promoted'

Christina Blacklaws, Law Society president 2018/19

In another decade, managing partners of legal firms may have a better idea about what is likely to work. The International Bar Association (IBA) has plans for an ambitious research programme aimed at discovering exactly that.

Sara Carnegie, the IBA’s director of legal projects, tells the Gazette: ‘The proposed project is still under discussion and not 100% agreed – and certainly not financed as yet – but the ambition is for a nine-year study, with checks carried out on the data every three years.’

The plan is to study women in private law firms, in-house, public sector legal and the judiciary in up to 15 countries. Carnegie explains: ‘We would look to monitor seniority. How many women work at a senior level in those places? What specific mechanisms, training or efforts are being made to improve gender equality?’

The research may also involve studying one woman from each sector in each country. ‘This would allow more of a deep-dive approach, but again, has yet to be decided in terms of whether it is viable or desirable,’ she adds.

Around the world, there are good intentions on equality and initiatives aplenty. The challenge for the legal profession is to move beyond the situation where, in former Law Society president Christia Blacklaws’ words: ‘Women are everywhere over-mentored and under‑promoted.’

Melanie Newman is a freelance journalist

2 Readers' comments