Shades of the Prison House: a history of incarceration in the British Isles

Harry Potter

Boydell Press, £25

★★★★★

Prison reformers such as John Howard, Elizabeth Fry, Joshua Jebb and Jeremy Bentham personified the passion to tackle the age-old conundrum of what constituted a perfect penal environment. This is the leitmotif in barrister Harry Potter’s tour d’horizon of incarceration in the British Isles. But Potter’s account, rooted in legal and official reports, letters and treatises, is not just about those charismatic reformers. He also scales the walls of Newgate, Pentonville and Broadmoor to unlock their secrets.

Above all, this is a human story, an often brutal depiction of being immured down the ages, from Anglo-Saxon times (600-1500), through the ‘experimentation with imprisonment’ (1750-1863) and the ‘age of enlightenment’ (1895-1965) to ‘safe and secure?’ (1965-2018).

A perennial concern has been the mental health of inmates. This was crystallised in the building of the red-bricked Victorian Broadmoor, designed by Jebb, as ‘an asylum for the criminally insane’. Broadmoor’s notorious inmates, such as ‘Yorkshire Ripper’ Peter Sutcliffe and ‘Stockwell Strangler’ Kenneth Erskine, might take a chilling hold on the reader’s imagination, yet Potter offers a different perspective. For Broadmoor’s approach ‘was far from the coercive methods of restraint used in Bethlem and elsewhere’, instituting a regime of ‘moral management’. This encompassed ‘strenuous exercise’, ‘steady occupation’ and ‘sustaining meals’, underscoring Broadmoor’s motto of mens sana in corpore sano (a healthy mind in a healthy body).

Curiously, the first full-time prison psychologist was not appointed until 1946, following a report by forensic psychiatrists William Norwood East and W.H. Hubert. They advocated that a special penal institution should cater for ‘abnormal and unusual types of criminal’. The psychiatric unit at Wormwood Scrubs was the first prison in the world to conduct group psychotherapy, as well as being the precursor to similar units at Holloway, Wakefield and Feltham; a psychotherapeutic prison was built at Grendon Underwood in Buckinghamshire.

Elsewhere in ‘The Nutcracker Suite’ – one of the book’s most absorbing chapters – Potter describes attempts in the Special Unit at Glasgow’s Barlinnie prison to adopt a therapeutic ethos, replacing ‘solitary confinement and brutality with arts and crafts’. One of the unit’s most famous guests was Jimmy Boyle. Branded by the press as ‘Scotland’s most violent man’, Boyle had been sentenced to life for a gangland murder. He went on to become a ‘celebrity criminal’, a sculptor whose work was exhibited at the Edinburgh Festival. As Potter observes, ‘[the unit] gave too much stress to the artwork of killers and too little concern for the anguish of their victims’.

This desire to alleviate the lot of prisoners has been reflected down the ages. Quaker Elizabeth Fry – here dubbed ‘Angel of the Prisons’ – visited Newgate prison in 1813. Aghast at the squalid conditions for women prisoners, with ‘drinking, gaming, fighting and swearing universal’, Fry was convinced ‘that the women could be helped to help themselves’. At Newgate she established the first school in British penal history; an ‘Association for the Improvement of the Female Prisoners in Newgate’ was also set up. Fry, ‘the very embodiment of enlightened prison reform’, called for the creation of a women-only prison (Grangegorman in Dublin would become the British Isles’ first in 1837).

John Howard’s interest in prisons was piqued by the fee system at Bedford county gaol, where ‘even those acquitted were detained until they had paid their fees’. This sparked 38 tours of the British Isles and seven on the continent, where he visited and revisited prisons collecting a tranche of data. His drive resulted in ‘two salutary enactments’ involving the removal of discharge fees and measures to counter gaol fever; he paid for the legislation to be printed.

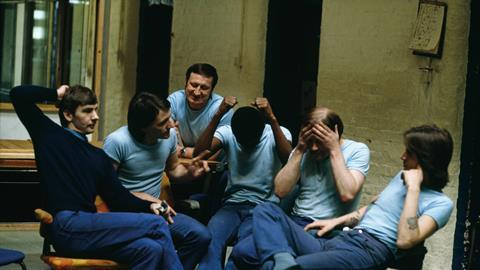

Potter is excellent too on the bricks and mortar. The design of Jebb’s Pentonville or ‘The Model’ (built between 1840-1842) rested on the idea ‘that a totally controlled environment could produce a reformed and autonomous individual’. One of the most sinister aspects of Pentonville was ‘that silence was all-pervasive in this well-oiled machine’, testimony to a regime that housed inmates in separate cells and insisted on them wearing masks while exercising (see illustration, below) so no communication with other prisoners was possible.

Jeremy Bentham toiled for 16 years on a ‘far-reaching penological experiment’, a ‘complete utilitarian legal system’ known as a ‘Pannomion’. He envisaged that ‘rational punishment’ would be imposed in a ‘Panopticon’, thus achieving ‘the greatest apparent suffering with the least actual suffering’. But his utopia would have been a ‘sterile desert, unfit for human occupation’, said one writer. Bentham ‘bitterly regretted’ the rejection of his project.

This powerful, superbly written history – replete with illustrations – offers some coruscating conclusions. Potter asserts that ‘the reality is that in the wider prison estate far more inmates are made worse than are made better. And this to protect the public!’

Nicholas Goodman is a sub-editor at the Gazette

No comments yet