In the face of stiff competition from international rivals, can the Commercial Court maintain its pre-eminent position?

The Michaelmas term starts in the Commercial Court on Wednesday with a new judge – Mr Justice Flaux – in charge of steering it through some potentially choppy waters, as rival international court centres eye any opportunities to compete for business.

Some issues have yet to show their hand, such as the impact the Jackson costs budgeting principles may have on high-value, complex litigation, given the cap was only raised to £10m in April.

The Ministry of Justice has also thrown into the mix controversial proposals for hugely ‘enhanced’ court fees. As the Gazette went to press, the MoJ was still ‘considering’ the responses to its consultation but there are indications it may pull back because of the potential damage it could cause to the competitive position of UK courts.

In the meantime, Flaux begins his new role with a checklist of concerns flagged up by practitioners in a review of the court earlier this year.

Commercial silk and part-time High Court judge Khawar Qureshi QC was asked by the lord chief justice to look at the court’s strengths and weaknesses and identify issues to be addressed. He surveyed 39 law firms and five chambers, and found the judiciary and quality of decisions were considered second to none.

But the views of a significant minority that costs are too high, case management and disclosure are unsatisfactory, and the use of IT before and during trial falls far short of ideal will give Flaux plenty of food for thought.

Drawing on the survey results, Qureshi also cautioned that a degree of ‘complacency’ had emerged about the position of the court as a forum of choice.

That is a trap Flaux is determined to avoid, using his experience on both sides of the fence. A commercial silk with 7KBW, his practice was split between commercial litigation and commercial arbitration. Since his appointment to the High Court in 2007, he has sat regularly as one of the 15 designated Commercial Court judges.

His appointment was greeted with enthusiasm, with one practitioner commenting: ‘He is very proactive and I can’t think of a better judge to be in charge of the court list.’

Anecdotal evidence suggests, says eDisclosure consultant Chris Dale, that Flaux is ‘rather more alive to the commercial imperatives of clients and their lawyers than some of his judicial colleagues, knows that “active management” implies something proactive, and that technology has moved on a bit since he was a pupil. We shall see’.

What is clear is the need for a steady hand, particularly given the important role the court plays in helping maintain the UK’s position as the leading centre for international legal services.

Since 2008/09, the number of claims issued in the Commercial Court has exceeded 1,000 a year. Its jurisdiction is wide, extending to any claim relating to the transaction of trade and commerce, as well as arbitration and competition matters.

What stands out is that there was a foreign party involved in 81% of the 1,100 claims issued during 2013/14 – up from 72% in 2008/09 – and in 48% of cases all parties were from outside the UK.

Research into its usage by communications consultancy Portland found the most common nationalities came from the US, Russia – the 2012 Berezovsky-Abramovich trial alone was reported to have generated £100m in legal fees – Kazakhstan, Switzerland, the United Arab Emirates, India, the British Virgin Islands, Panama, Bahrain and Germany.

The court’s international image was given a modern twist with the opening of the prestigious Rolls Building in 2011. But lack of IT and limited Wi-Fi have long been cited as major shortcomings, comparing badly with the commercial courts in Dubai and Qatar. A viable ‘e-working’ solution cannot come soon enough for practitioners (see box below).

The quality of the judiciary is high and clients feel they get a fair hearing in a relatively timely manner. Those are London’s great strengths

John Bramhall, London Solicitors Litigation Association

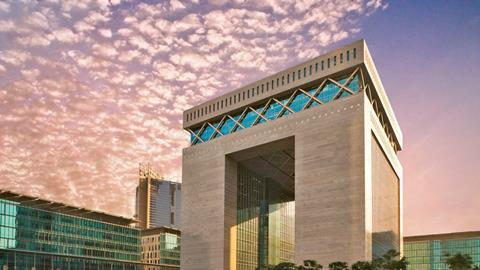

Tony Guise, chair of the Commercial Litigation Association, canvassed members’ views on the competition for London’s crown. ‘There is a real danger Singapore and/or New York will steal a march – and let’s not forget the DIFC Court in Dubai [pictured],’ he says. ‘One member takes the view Singapore has the work now and it won’t be letting go any time soon. With the rise of the far east as a market, he believes Singapore will become the premier jurisdiction for dispute resolution in five to 10 years’ time. Confidence placed in London’s pre-eminence by way of dispute resolution clauses is, in his view, misplaced.’

John Bramhall, chair of the London Solicitors Litigation Association, believes London still has the edge. ‘The Commercial Court continues to attract large numbers of international clients who respect our systems, our law and our judiciary,’ he says. ‘It may not necessarily always be the cheapest place to resolve a dispute but the quality of the judiciary is high and clients feel they get a fair hearing in a relatively timely manner. Those are London’s great strengths.’

Flaux will be keeping an eye on whether work which would otherwise come to London is going elsewhere.

While he acknowledges nothing can be taken for granted, he is confident of the Commercial Court’s strengths.

‘The Singapore court is very much feted, but I don’t regard it as competition as such because it is essentially dealing with far-eastern cases, most of which wouldn’t have come here anyway,’ he says. ‘They might have arbitrated here but, given Singapore is also a well established arbitration centre, the reality is that area of work is self-contained.’

He points to discussions about an English-language court in Hamburg but says that is still in its early stages.

‘The DIFC Court is staffed almost exclusively by retired Commercial Court judges so I must be a bit careful what I say,’ he says with a smile. ‘It’s a pretty good set-up but it largely deals with Middle East cases – a dispute between a Delaware-registered company in the US and a German company isn’t going to be litigated in Dubai.’

He does not view arbitration as competition. ‘Rather, we complement each other in terms of our role supervising arbitration applications and enforcement,’ he says. ‘Historically, a lot of contracts contain London arbitration clauses and they aren’t suddenly going to say “we would rather litigate in Singapore or Dubai”.’

Flaux has seen no signs of demand for the court falling away. Indeed, earlier this month the Law Society predicted that the UK legal services sector would return to pre-financial crisis rates of growth, with reports from practitioners of a continuing surge in disputes work.

There are always the core areas of work in terms of shipping, and insurance and reinsurance, as well as the disputes arising out of the 2007 crisis, the judge says.

‘Derivative disputes of one kind or another are very much the flavour of the year,’ he notes. ‘I have only just started in this role but I have a sense that the Russian oligarch cases have rather run their course. But moves to impose sanctions on Russia are likely to create their own area of litigation.’

The London legal system has certainly shown itself remarkably adept at providing a platform to resolve disputes arising out of situations no one could have foreseen, argues litigator Graham Huntley, founding partner of Signature Litigation and a member of the Commercial Court Users’ Committee.

‘Some things are being done better in other places but I have yet to be convinced they are so much better that it is making them more attractive than London,’ he says. ‘But it would be disastrous if we became complacent.’

While there are pressures in terms of costs and technology, Huntley says success is not down to individual factors but the interaction of the physical structure of the court, the quality of the judicial process and the resources put into the system – including the level of co-operation from parties – so it can function at its best.

But will judges be able to do the best job they can if costs budgeting issues start to eat away at judicial time and resources, as they have in other courts?

‘It will be a pain for us and for judges who don’t really want to deal with these detailed aspects,’ Bramhall says. ‘But, in theory, it shouldn’t be difficult because we should already be keeping clients informed of the ongoing costs.

‘Back in the real world, however, there is a major difference between those two processes. It is frustrating being forced down the costs budgeting tick-box approach because what you always know is that, however good an estimate you make, you will be wrong. That is the one certainty in life. How that will play out as to how often and how receptive the court will be to you going back again and again, time will tell.’

What is helpful, Bramhall says, is that the recent appeal decisions around Mitchell ‘have restored a level of sanity to the process – though I am sure there will still be major issues’.

An approach that makes costs more predicable must be a good thing, says Kenny Henderson, London senior associate with US firm Covington & Burling. ‘The Jackson reforms are less appropriate for complicated disputes where parties are less sensitised to costs, and it is important that any changes don’t make the court a less attractive jurisdiction. But I have sympathy with the court and the MoJ trying to balance those sometimes conflicting objectives.’

Building credibility

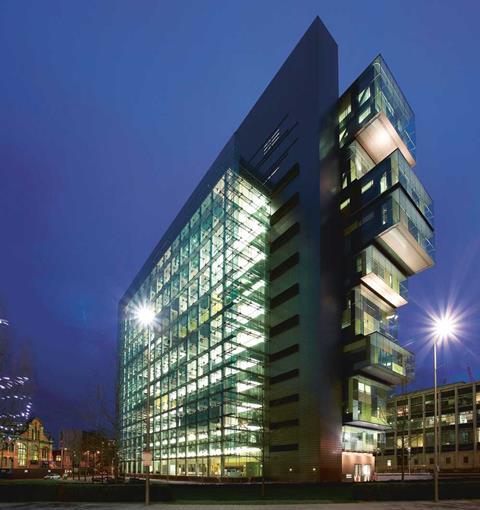

The Rolls Building, home to the Commercial Court since 2011, is the largest specialist centre for the resolution of financial, business and property litigation in the world.

However, describe it as a ‘state-of-the-art facility’ and the response from Commercial Litigation Association chair Tony Guise is cutting: ‘Maybe – if we were still in the 20th or even the 19th century’. He points out that the building has been without a modern IT system since a £10m upgrade attempt was cancelled in 2012. All filings still have to be made on paper.

With three super courts, 31 court rooms and 55 break-out rooms, the £300m building brings together the work of the Admiralty and Commercial Court, the Technology and Construction Court, and the Chancery Division of the High Court. Around 7,000 claims are issued each year in the building, with about 1,200 listed for hearing, generating just under £5m of income.

In May, the MoJ announced it had awarded a contract for an e-working solution – Thomson Reuters’ C-Track – at a cost of about £5m. Assuming no hiccups, its introduction across the building’s different jurisdictions should be completed by the end of 2015.

‘In an ideal world,’ says Mr Justice Flaux, ‘we would have started with e-filing of documents leading through to paperless trials. But I don’t think you can blame the building – we are where we are. Bear in mind that we have several thousand cases on the go at any one time, so you need a much more sophisticated system than in a smaller court centre. The private initiative used in a number of Commercial Court trials of electronic bundles is working well and I do think paperless courts will be feasible in my lifetime.’

For Guise, the Rolls Building is a ‘nice environment’ to work in with some ‘amazing art’ but its courts compare unfavourably with those at the Manchester Civil Justice Centre (pictured). ‘Staff are very helpful,’ he adds, ‘but major problems remain that were there on the day it opened: no online access to the court file; paper files being lost; poor public Wi-Fi; and too few counter staff.’

A Court Service spokesperson says it is keen to improve Wi-Fi provision and will decide what to do once it has seen the results of trials in other courts.

And while some commentators believe the courts service missed a trick by not offering space for alternative dispute resolution, others argue that loss was outweighed by the benefits of bringing more of the court system into the building.

Flaux has yet to experience a case which requires costs budgeting. ‘All I can say is I am glad that it has come in after some of the glitches have been ironed out in the other courts,’ he says. ‘I don’t think it will be the nightmare burden some fear.

‘The approach I adopt is that these cases are being run by experienced City firms with sensible solicitors and counsel, and if they say “we need to spend X on disclosure and Y on experts” then who am I to contradict them? But there has to be an overall controlling mechanism to stop cases running out of control, because then parties can’t settle because the dispute becomes about the costs.’

He believes the Commercial Court has a ‘distinct advantage’ over other courts because judges manage their own cases: ‘I am very keen on docketing, providing there are the resources. Parties prefer to have one judge dealing with the case even if it means having a case management hearing outside London if the judge is out on circuit.’

He is also ‘very much alive’ to taking steps to limit disclosure. One suggestion in the Qureshi report was to use the Redfern schedules used in international arbitration. But Flaux cautions: ‘My experience at the bar was you could spend more time arguing about them than if you did it in the standard way. But the burdens imposed by the disclosure exercise are something all judges have in mind and control of disclosure demands robust case management.’

In August, the MoJ increased court fees based on cost recovery, despite objections from the Law Society, the City of London Law Society and the senior judiciary, who made it clear they did not support government policy that the justice system should be self-financing.

The question now is whether the MoJ will actually take the next step in imposing the ‘enhanced’ fees, which would result in the cost of issue and hearings going up under one option from £2,960 to more than £20,000.

The MoJ argued there was a ‘strong case’ for setting fees above the cost of proceedings for parties who can afford them and benefit from litigating here, to reduce the net costs of the courts to taxpayers. However, its impact assessment was slated by the independent Regulatory Policy Committee as unfit for purpose.

‘It is unacceptable for the state to try to make a profit from its citizens’ misfortunes,’ says Stephen Denyer, the Law Society’s head of City and International. ‘We are also very concerned that these enhanced fees would make London a less attractive jurisdiction internationally – the fees may seem paltry against the sums involved but other jurisdictions are likely to seek a competitive advantage through lower costs.’

As part of its consultation, the MoJ commissioned a comparative analysis of the costs of court services in the key rival centres to London. It found that it was substantially cheaper to pursue a business dispute here than in Singapore, Australia or Dubai, particularly in longer cases, because the courts here do not charge a daily hearing fee. However, the fees charged in New York and Delaware are already lower than here.

‘After a great flurry, the enhanced fees issue seems to have gone quiet,’ Flaux says.

‘It will depend on how wide the government opens its mouth frankly. People would stand possibly slightly higher issuing fees, but any other sort of fee system would be potentially worrying. It seems the government is shying away from daily user fees, which have all sorts of hidden traps, but any significant change could be seized on by competitors as an indication that our system is too expensive.’

The cost of litigating is already causing enough concern, according to Qureshi, chair of lobbying organisation TheCityUK’s legal services and dispute resolution group. ‘We need to grapple with this issue or our system may lose its edge and that will be a matter of great regret,’ he says. ‘It won’t affect my generation but it will affect the generation to follow.’

He wants to canvass the idea of costs assessment being split off entirely, above a defined level of costs claim, and dealt with by costs judges alone on an expedited basis, with more information than is currently provided to a judge undertaking summary assessment. He also suggests introducing a random selection of ongoing and concluded cases where a dedicated costs judge could call in all of the billing material.

‘I recall during the early part of my career spending days in front of a taxation master arguing about the minutiae of costs after a heavily fought commercial case ended and not enjoying it one bit,’ he says. ‘But its transparency effect was significant.’

Flaux says there is the possibility in a complicated case for a judge to call in a costs judge to assist with the budgeting: ‘Whether that will happen only time will tell. But if we have parties at each other’s throats over costs it will be a learning curve for the judges.’

While practitioners are hoping Mr Justice Flaux will live up to his reputation for being proactive, there was also a plea in the Qureshi report for any change to be kept ‘measured and simple’ to avoid adding to bureaucracy and expense.

So, what are the judge’s plans for the court? ‘My view is that, by and large, if it ain’t broke don’t fix it,’ he says. ‘I can’t see any point in any more sweeping reforms. We have been through all of that and come to a position where the rules work reasonably well, provided they are applied flexibly and provided judges are prepared to exercise their case management powers.

‘A period of consolidation – not just in the Commercial Court but across the justice system generally – will do nobody any harm.’

Grania Langdon-Down is a freelance journalist

No comments yet