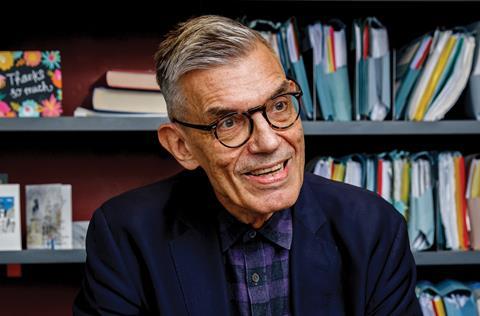

Wesley Gryk gave up a lucrative career as a Wall Street corporate lawyer to take up the mantle of penniless asylum seekers and the rights of lesbian and gay couples. Jonathan Rayner met him

BIOG

BORN

Manchester, Connecticut, USA

EDUCATION

Harvard College and Harvard Law School (graduated 1975)

College of Law (1986-89)

ROLES

Judicial clerk to Constance Baker Motley (1975-76)

Associate, Shearman & Sterling, New York and Hong Kong (1976-80)

Legal adviser, UNHCR (1980-81)

Deputy head, research, Amnesty International (1981-86)

Solicitor, BN Birnberg & Co (1989-95)

Founder and partner, Wesley Gryk Solicitors (1995-present)

KNOWN FOR

Pivotal role in winning legal recognition of lesbian and gay couples in UK law

Harvard Law School graduate Wesley Gryk used to be a Wall Street lawyer. But the rich rewards of prestige and money did not chime with his ambition to make a real difference to people’s lives. And so he chose a quite different career path, electing to work for the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) and Amnesty International. And, since 1995, senior partner of Wesley Gryk Solicitors, his own firm, which acts out of offices in Waterloo, south London. The firm represents a wide range of immigration clients, including asylum seekers and – perhaps more surprisingly – the occasional circus performer.

Rights champion

Looking back on his career, Gryk is most proud of his work campaigning, in conjunction with charity Stonewall, for gay and lesbian couples to have the same immigration rights as married and unmarried heterosexual couples. ‘This was the 1990s, when even Amnesty International didn’t recognise gay and lesbian cohabitation rights,’ Gryk explains. ‘It was a slow process of wearing the Home Office down by arguing that a de facto policy was being created.’

Finally, in October 1997, the Labour government announced an inclusive unmarried partners’ policy for immigration purposes. The new policy, ‘the unmarried partners’ concession’, recognised partners in gay and lesbian relationships. ‘It was the very first legal recognition of lesbian and gay couples in British law,’ Gryk recalls.

This was a significant landmark in the evolution of gay rights. But Gryk has also been targeted by the press and politicians for his work. Wesley Gryk Solicitors was among 21 firms pilloried in 2003 in the tabloid press for costing the taxpayer more than £1m a year in legal aid fees. Was Gryk a fat cat millionaire lawyer? ‘Far from it,’ he replies. ‘We had never made more than £10,000 a year profit by that time, which is one reason I struggled to persuade anyone to join me as a partner.’ Did it hurt to be, albeit wrongly, publicly named and shamed? ‘I was more concerned that some indignant citizen might firebomb our office and injure or kill a colleague.’

As home secretary Theresa May also had Gryk’s firm in her sights. She told the 2011 Conservative party conference that one of the firm’s clients had been granted leave to remain in the UK on the spurious grounds that he and his partner had a pet cat in common. ‘I’m not making this up,’ she told the party faithful. She or her speech writers had got it embarrassingly wrong. She had been corrected on Twitter even before she sat down.

Gryk was born and brought up in Manchester, Connecticut, where, he says, he was ‘educated by the nuns’ at a Catholic high school. His father was a lawyer in a small local practice and Gryk was content to follow him into the law, graduating from Harvard Law School in 1975.

A GLOBAL FOCUS

Since becoming a solicitor in the UK, Wesley Gryk has had the opportunity to take part in several international human rights missions. ‘I was in Iraq for the Saddam Hussein trial,’ he recalls. ‘It was clearly a political trial, but it was important that it was fair. I’m against the death penalty, but believe that perpetrators of human rights violations must be brought to justice.

‘Another mission was to South Korea. There was a military government at the time and we were stopped at the border and searched. We insisted on being searched, for our own safety, in the public eye. One local guy was sent out from a meeting to do some photocopying. He was gone for two hours while the security services questioned him.

‘My proudest achievement, however, was a relatively low-profile mission which I undertook with an Amnesty International researcher. It was in Sierra Leone during the 1990s civil war there.’ Gryk and the researcher applied, initially to no avail, to have access to Pademba Road prison in Freetown. The prison was notorious and held up to 200 individuals without charge or trial as alleged rebels. An average 10%-20% of prisoners held there, it was said, would die as a result of the appalling conditions.

‘On the penultimate day of the mission, we finally got access to the prison and spent our remaining time in the country interviewing and taking brief details of every prisoner. These included some who were so ill they had to be carried by their fellow prisoners to see us. Amnesty International published a report within a few weeks listing every prisoner being held without charge or trial. Shortly afterwards, every prisoner on the list was released.’

He went on to secure a judicial clerkship with Constance Baker Motley, the first female African-American federal judge, appointed in 1966. Such clerkships, unknown in the UK, are much sought-after by high-achieving recent graduates from US law schools. They provide access to the judicial process and are attractive to future employers because the graduate gains not only legal knowledge, but also an insider view of the court system and the ability to consider cases from the court’s perspective.

But perhaps more importantly for Gryk’s future, Motley was a committed civil rights activist. The first African-American woman to argue a case before the US Supreme Court, it was Motley who, in 1962, enabled James Meredith to become the first black student to attend the previously whites-only University of Mississippi. Gryk, perhaps inspired by her example, was to go on to become a staunch defender of the rights of the underdog, in his case representing penniless asylum seekers, lesbian and gay couples with no rights under the law and other powerless groups and individuals.

But we race ahead. After his stint as a judicial clerk, he joined the Wall Street office of global law firm Shearman & Sterling. The firm acts for many of the world’s leading corporations and financial institutions. ‘It is also keen to send trainees on intern ational secondments,’ Gryk notes, ‘which is how I came, after two years in New York, to move to Hong Kong for a year to help a senior partner establish an office.’

Career epiphany

Gryk enjoyed Hong Kong, but he was about to experience a life-changing epiphany. He takes up the story: ‘I’d just seen the 1979 film The China Syndrome, in which Jane Fonda, playing a journalist, saves the world from nuclear disaster. Perhaps it left the germ of an idea in my mind because, when it was time to leave Hong Kong, I asked myself whether I really wanted to return to New York and get back on to the conveyor belt of working hard and becoming a partner. Was that really all I wanted out of life and wanted to contribute?

‘I spotted an advertisement in the Economist magazine for a London-based legal adviser and deputy representative for the UNHCR. I applied for and got the job.’ He stayed there for a year before moving to Amnesty International, London, as deputy head of research. He was there for five years before, ever restless, he decided he would be able to do a better job for victims if he got himself an ‘indigenous qualification’, becoming a UK solicitor.

He enrolled at the College of Law to read for his common professional examination. ‘Those were the good old days when students still got grants,’ Gryk recalls. ‘I had a grant from the Inner London Education Authority.’ Was the course very demanding? ‘I seemed to spend a great deal of my time watching Neighbours on TV.’

Our first clients were very complicated cases that nobody else would take on. There were lots of Somali refugees in the country and we were able to help some of them

Upon completing his studies at the College of Law, Gryk joined BN Birnberg & Co (Birnberg Peirce since 1999), a London firm well-known for its focus on civil liberties and human rights. It was there that he completed a training contract before leaving, after six years, with Barbara Coll to found Wesley Gryk Solicitors in 1995. (Coll, then a paralegal, had not been able to secure a training contract; Gryk was able to offer her one.) ‘We were renting three rooms over a Balti house on the Strand,’ Gryk recalls. ‘The two of us hired a secretary, then busied ourselves organising the furniture while waiting for the telephone to ring. Our first clients were often very complicated cases that nobody else would take on. Fortunately, at least for us, there were lots of Somali refugees in the country and we were able to help some of them.’ The refugees had fled Somalia during its decades-long civil war. There are now more than 100,000 Somalia-born residents in the UK.

Gryk continues: ‘I’d begun to handle increasing numbers of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender matters while at Birnberg and some of these cases also began to arrive in our new offices. We survived.’ The firm has endured and now comprises more than 20 people, including four partners, nine solicitors and six trainees as well as paralegals and support staff.

Legal aid departure

It has not, however, been all plain sailing. In 2004, in Gryk’s own words, the firm ‘flounced out’ of the legal aid system when it became apparent that government cuts ‘were making it impossible to provide the same level of representation to our legally aided clients as to our privately funded clients’. This was a huge departure because for the first decade of the firm’s existence it was primarily a legal aid practice representing indigent individuals.

Has abandoning legal aid changed the firm’s ethos? ‘We have managed to establish a reputation as a firm which does high-quality work for individuals and entities at both ends of the economic spectrum. We give all our clients, from whatever background, the same equally skilled and dedicated attention to their cases. And we train all of our young lawyers to be all-rounders in the field of immigration so that, when approaching a particular case, they are aware of all the immigration law angles that might come into play.

‘We do this by taking a Robin Hood approach, financing our work for the less well-off by charging fair rates to those who are able to pay them.’

We train our young lawyers to be all-rounders in the field of immigration so they are aware of all the law angles that might come into play

Gryk mentioned representing ‘the occasional circus performer’ at the start of the interview to which he returns. ‘I have made dozens of successful applications to Arts Council England for endorsement of Tier One [exceptional talent] migrants. If you are a recognised or emerging leader in the arts, digital technology, humanities, science, engineering or medicine, you can apply to be endorsed by an official body in your field, such as the Arts Council. The visa enables you to live and work in the United Kingdom for up to five years, after which you may be able to settle. You can also bring your family members with you.

‘I’ve acted for a wide spectrum of talented individuals, including classical musicians, pop and rock singers, an orchestra conductor, a film costume designer, theatrical producers, conceptual artists – and circus performers.’

He has no regrets, then, about turning his back on the glittering rewards of Wall Street? ‘None at all. In fact, two of our partners, Alison Hunter and myself, come from corporate backgrounds, having trained in the City and on Wall Street respectively. We both came to our firm determined to bring the same standards of excellence and attention to detail to the representation of ordinary people facing immigration challenges.’

What does the future hold for Gryk? ‘The world is a volatile place at the moment. For instance, youngsters don’t realise how recently more inclusive attitudes and policies towards the LGBT community have evolved. It is great to have been part of those changes, but it could all come crashing down with some of the mad men that are now in power.

‘The result of the referendum on whether or not to stay in the EU tore me to bits. It divided UK society and gave bigots a licence to say horrifying things about immigrants. Brexit has left my clients living in fear of losing their right to remain. Nobody, including the politicians, knows what’s going to happen next. And above all, there is the very real danger of crashing out without a deal.’

Gryk will be 70 next birthday. Has he given much thought to retirement? ‘Retirement? I feel as though we have been writing my obituary and I can now go home and take a long rest! More seriously, I have sold half the building to my partners by way of succession planning. One of the great contributions of my life has been creating a like-minded group of people at Wesley Gryk Solicitors and they will continue the good work.’ He pauses. ‘A client gave me a handmade leather wallet from Pakistan with the inscription in silver: “Robin Hood Wes”. That’ll serve nicely for my epithet.’

Photo credit: Darren Filkins

1 Reader's comment