Many have questioned the price tag of the new super-exam – but there are more serious concerns, about the impact it could have on access and the threat of a ‘two-tier’ profession

The University of Leicester is as keen as any leading academic institution to ensure it is not issuing PhDs of a dubious standard, so it is willing to pay external examiners to pay proper attention to theses that typically weigh in at 100,000 words. These are the product of a candidate’s close focus on a specialism that took at least three years; the external examiner, an academic, is paid £175 and up to £250 travel expenses.

Cost

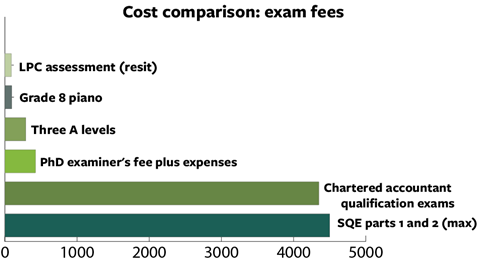

Exams that professionals sit in order to qualify appear expensive by comparison. A chartered accountant currently spends £4,350 on exam fees, and as the Gazette reported on 12 November, the Solicitors Regulation Authority estimates that the total cost of the Solicitors Qualifying Examination, taken in two parts, will be up to £4,500.

SQE 1, which will test legal knowledge through a series of computer-based assessments, will cost between £1,100 and £1,650 (there is also a written element). Fees for SQE 2, which will test practical legal skills, will range from £1,900 to £2,850.

Whereas most higher education institutions price the cost of exams into students’ academic fees, the SQE will be run and assessed by Kaplan, an independent external organiser, to underline its objectivity.

Kaplan includes in the exam fee ‘preparation and administration of the actual exam papers’, so this is not just a fee for marking papers and assessments. A spokesperson for Kaplan tells the Gazette that setting questions and tasks ‘would be done afresh for each round’.

Kaplan won the eight-year appointment in a competitive tender. But as the SRA again postpones the introduction of SQE – to 2021 – concerns about aspects of its contents and assessment methods remain unanswered.

How has the SRA devised an assessment brief for SQE 1 that will cost candidates £1,100-£1,650? SQE 1 is billed as testing ‘legal knowledge and will be an academic exam’. It will be taken around the time of graduating from a degree or equivalent. Under the SRA’s current proposals, this does not have to be a law degree.

Controversially, this is the stage that makes heaviest use of computer-based assessment, including multiple choice questions, but at the upper estimate costs six times as much as a PhD examiner assessing a highly individual thesis.

SQE 2 looks to make more intense demands on examiners, as the intention is to test issues such as skills in client interviewing and providing advice. This will be a practical skills exam to be taken, most likely, after two years of work experience. Hence, perhaps, the higher price-tag of up to £2,850.

‘The fees announced [amount to] a great deal of money,’ says Alan East, academic lawyer and chair of the Law Society’s Education and Training Committee. ‘I’m concerned that there are currently no funding mechanisms available to help fund the SQE. The legal profession must be open to everyone and there should never be barriers based on cost.’

A masters degree from East’s own Coventry University costs around £10,000 a year – which includes tuition, supervision and final assessment. To have SQE 1 and 2 weigh in at almost half that total strikes many as over the top – though it is roughly equivalent to the exam fees for a chartered accountant.

The Society and its Junior Lawyers Division (JLD) are also concerned about cost. A Society spokesperson points out: ‘There is as yet no funding mechanism to provide loans for SQE assessments.’ This means that ‘any fees will have to be self-funded by candidates or firms, which would disadvantage students with less financial means’.

Two tiers or helpful flexibility?

Should the SRA be at loggerheads with a body that has the moral authority of the JLD? You would think not from the SRA’s reasoning for the SQE. The idea of a single exam is not just to control the ‘quality’ of those entering the profession, but to do so in such a way as to allow multiple (including cheaper) routes. If you can pass SQE 1, the argument runs, it should not matter if you got great marks by reading a ton of law in a public library while juggling caring commitments, or if you stumped up £10,000 or more on time at an established law school.

As an SRA spokesperson tells the Gazette: ‘SQE aims to address the problem of the need to pay large, up-front costs – up to £16,700 for a Legal Practice Course (LPC) – with no guarantee of a training contract or becoming a solicitor. Some aspiring solicitors find they cannot progress, while others are put off trying to qualify altogether.’

Indeed, for those who travelled a ‘gilded’ route into the legal profession – top university to training contract, secured before law school – hearing the experiences of those with a more difficult journey can be humbling. SQE, the argument runs, removes hurdles by being less prescriptive.

‘Gaining the skills and knowledge to pass SQE 1 and 2,’ the SRA adds, ‘can be made while working, potentially as a paralegal or through the apprenticeship route.’

Alan Milburn, the former cabinet minister whose work on social mobility shaped the debate and policy response of the professions to social mobility challenges, was clear that having ‘multiple entry points’ to a legal career was critical to achieve better outcomes.

Viewed this way, the SQE is of a piece with legal apprenticeships and the ability to prove ‘equivalence’ of relevant experience to an undergraduate degree – a return to the days when, as a few who reached the top of the profession showed, a lawyer could rise via workplace experience and serious swotting for the old Law Society exam.

The SRA is also keen to rebut any suggestion that banks will not lend candidates the funds to go through the new system. ‘We’ve spoken to the banks about career development loans,’ a spokesperson tells the Gazette. ‘At this time, there’s no reason to think that bank loans would not be available in the usual way.’

The new system will create savings, they add: ‘The [SRA’s] education and training [team] also wanted to make the point that the cost of the Professional Skills Course has not been factored in to potential savings. They think it’s around £1,500 or so. This is usually a cost borne by employers during the period of recognised training, and therefore a cost that could be offset by SQE.’

So what is there to mind? The frontline regulator is certainly not hell-bent on setting back the clock on access to the profession – its intention is quite the opposite.

And yet the JLD, whose committee includes people who had a long route into law and some who are paralegals on what they hope is a journey to the roll, remains sceptical about the SQE proposals as they stand. Chair Adele Edwin-Lamerton was one of the Law Society’s first social mobility ambassadors, and has written about the way a difficult home life affected her ability to meet what looked like essential criteria to secure a training contract.

She does not feel SQE cost concerns have been addressed: ‘£4,500 is a significant amount of money for an examination only and, at present, loans aren’t available to fund taking an assessment,’ she told the Gazette earlier this month. ‘This will hugely affect those from lower socio-economic backgrounds or those who don’t have an employer willing to cover the cost.’

At issue, despite SRA assurances, is the fact that neither funding nor loans are traditionally available for a course with no exam attached – or an exam which has no preceeding course.

Edwin-Lamerton (and others) worry that ‘the two-tier education that will emerge is already apparent’. But why?

There is a fear that principles around liberalisation are not suited to a professional environment – that flexibility and transparency do not necessarily lead to a system that is genuinely open and accountable. In an uncertain environment, there is a retreat to the traditional, and the tried and tested. Viewed this way, the SQE could increase the cachet of traditional blue- chip routes to law.

To be sure that future employers can ‘read’ the quality of your achievements and abilities, candidates who are in a position to do so reinforce the prejudices of those hiring by retreating to old certainties. Or, perhaps more likely, legal employers who are unsure of what the SQE can tell them about the sort of candidate they are getting have an unspoken requirement that a good law school and good A-levels – not the SQE – is the reassurance they need.

If either of these scenarios proves to be the case, the SQE has provided false hope to candidates, and added as much as £4,500 to the cost of qualification – on top of (not instead of) fees for a traditional law school.

Other concerns remain, not least related to whether multiple choice questions – for SQE 1, 680 over three exams – can test legal knowledge to a satisfactory standard. But this is one aspect where critics note there is not yet enough information to make a judgment. Are critics ignoring the consistency in assessment that has sometimes been found lacking in the current system?

Given that we do not (and cannot) know, the delay until 2021 for the SQE’s introduction and an 11-year transition for those who have already started on one of the old routes to qualification are welcomed by all. As East says: ‘I am keen for the SRA to take the time it needs to get the SQE right and allow time to ensure the assessment methods work.’

No comments yet