The low down

A recent photograph of our Supreme Court judges, taken after the retirement of Lady Hale, proved a lightning rod for criticism of judicial diversity. All had been barristers, all were white, 10 had been to Oxford or Cambridge and there were more blue neckties in the photograph than women. But change takes time, defenders of the status quo suggest – look at the pipeline, they add, and you will see a more diverse group on a journey towards the higher courts. Lord Sumption famously suggested 50 years of gradual improvement would deliver a Supreme Court bench that was 50% female. But the pipeline does not run smooth. Several judges have instigated their own discrimination claims and a recent report by Justice was scathing. Yet some supporters of a more diverse bench are asking: are some of the barriers to entry self-imposed?

Among judges, ‘racism both direct and indirect is still prevalent, especially among the senior judiciary as they come largely from a social stratum of society where they have little or no contact with ethnic minorities save as defendants, clients or witnesses’. So wrote Peter Herbert, chair of the Society of Black Lawyers (SBL), and a Crown court recorder and immigration judge, in a written submission to court in 2019.

Herbert is suing the Ministry of Justice for race discrimination. Part of his claim relates to disciplinary action taken against him by the Judicial Conduct Investigations Office. He was accused of implying in a speech that an Electoral Commission decision on Lutfur Rahman, the former mayor of Tower Hamlets, was racist.

A four-strong disciplinary panel, headed by a senior High Court judge, Mrs Justice Laing, and including two members of Indian heritage, was convened. The panel’s reasoning included an assertion that even if the implication was inadvertent, Herbert’s offence was particularly serious because he was ‘a predominant BME human rights lawyer’ speaking to ‘listeners who were predominantly BME people.

‘As a prominent BME lawyer and part-time judge [he] should have taken particular care,’ the panel concluded.

The panel was indicating that Herbert’s views were likely to command particular respect because of his characteristics and those of his audience. Herbert is of African heritage and his comments about Rahman had been made to a predominantly Bengali audience. It is unlikely that ethnicity would have been mentioned, he maintains, had he been a white judge speaking to a white audience. He argues that assumptions about ‘BME people’ and the way they all think are implicit in the panel’s analysis.

‘The panel would never have dared write that the speaker’s behaviour was exacerbated because he is “a prominent Jewish human rights lawyer addressing a predominantly Jewish audience”,’ Herbert tells the Gazette.

I just didn’t think that the judiciary was looking for people like me. There was no JAC and no initiatives to attract solicitors

Tan Ikram, district judge

The MoJ failed in its attempt to have this part of Herbert’s claim struck out. But it succeeded in respect of a different head of claim – that by appointing a disciplinary panel that did not include a black African member the MoJ had subjected Herbert to ‘unwanted conduct related to race’.

It will come as a surprise to many that Herbert’s case, listed for hearing this September, is one of several claims by judges concerning discrimination in the pipeline.

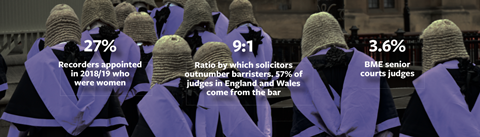

Collectively they seem to speak to wider questions over diversity and representation in the judiciary. A report from the human rights charity Justice published last month confirmed that despite decades of initiatives to widen the pool from which judges are drawn the vast majority remain – particularly at senior levels – white, male and from a bar background.

In the two years since Justice’s last report, the chances of appointment have improved for women. However, the small number of female judges overall, combined with likely retirements in the coming years, mean that, in Justice’s words, ‘progress is fragile’. The same period has seen the number of ethnic minority judges in the senior courts fall. Despite outreach efforts leading to an increase in applications, these have not led to more appointments.

While the statistics for BME judges are poor, within that group they are even worse for black judges. All four of the serving ethnic minority judges in the senior courts are of Asian origin, as are all of those said to be ‘in the pipeline’. To date there has only been one judge of Afro-Caribbean origin in the High Court or above – Dame Linda Dobbs, who retired in 2013.

In 2017, Justice recommended that ‘targets with teeth’ should be imposed on selection bodies, with monitoring, transparency and progress reporting to the Commons Justice Select Committee. This call is reiterated in its latest report.

Herbert agrees. ‘They are long overdue and have worked in other parts of the justice system,’ he says. ‘All BME, female and candidates with a disability who pass the access suitability test should be given interviews.’

He is also an advocate of race training for appointment panels as well as judges. ‘My practical experience is that race and gender mentors who [meet with] employment tribunal judges once a month do impact on behaviour and practice.’ By contrast, ‘theoretical discussions one or two days a year produce a momentary bounce of insight that rapidly disappears’.

Last year, lawyer MP David Lammy heavily criticised the judicial appointment system, telling the Justice Select Committee: ‘Had we stuck with the old tap on the shoulder, we would have more diversity today than the £10m situation we set up, with a whole load of forms and a whole load of systems that still seem to weed out ethnic minority candidates’.

The Judicial Appointments Commission (JAC), which Lammy described as ‘complacent’, has had only two people of Afro-Caribbean origin on its 12-strong panel of commissioners since it was set up in 2006 and currently has none – although it does have four BME commissioners, including chair Lord Kakkar.

Like Herbert, Lammy’s recommendation as part of his 2017 review of the judiciary was to introduce targets to achieve an ethnically representative judiciary, a proposal the government rejected. Lammy has since said he regretted that he did not recommend quotas; shadow attorney general Shami Chakrabarti has backed their introduction.

‘Recruit from beyond independent bar’

‘The task of judging is difficult and demanding, and the range of cases in which judgments must be made is extremely broad. The quality of those judgments will be vastly improved as a result of the different perspectives brought to decision-making by those with different characteristics and life experiences. We have taken evidence from several judges who have lamented the absence of judicial colleagues from different social and ethnic backgrounds, with whom they can discuss particular aspects of a case before them. The narrow demographic of the existing judiciary inevitably leads to a narrowing of experience and knowledge. Ensuring a diverse range of perspectives requires looking beyond appointments primarily from the independent bar and recruiting individuals with diverse professional backgrounds – solicitors, chartered legal executives, academics, and government and in-house lawyers. Not only do these pools tend to be more diverse in terms of ethnicity, gender and social background, but their different training and practical experience will also result in valuable cognitive diversity.

‘The consequence of not recruiting from a wide enough pool is necessarily that the institution is not benefiting from the best available talent. As Lord Neuberger has asked: “why are 80 per cent or 90 per cent of judges male? It suggests, purely on a statistical basis, that we do not have the best people because there must be some women out there who are better than the less good men who are judges.”.’

Judicial Diversity Update Report 2019, Justice

Sumption assumptions

Proposals for affirmative action were derided by Lord Sumption in 2012. He said an emphasis on personal experience would lead to the fragmentation of the judicial function, with ‘countless sub-groups, each with their own particular and equally relevant experience’ requiring consideration.

‘It leads to an attitude of mind which treats appellate courts as a sort of congress of ambassadors from different interest groups,’ he said. ‘I cannot be alone in regarding this as a travesty of the judge’s role.’ Sumption did, however, accept that there was ‘a widespread feeling that an undiverse bench lacks legitimacy’. But, he added, it was unclear whether the public would prefer faster progress towards a diverse judiciary if it required the partial abandonment of selection on merit.

While Justice believes that ‘diversity is integral, not contradictory or secondary, to merit’, some within the legal sector remain to be convinced.

‘It is highly patronising to suggest that BME people will respect the judiciary more if it has more BME judges,’ says Andrew Tettenborn, a professor of commercial law at Swansea University. ‘BME people, like everyone else, are perfectly capable of telling the difference between a competent and an incompetent judge.’

Tettenborn believes the current rules concerning appointments aimed at increasing diversity are likely to result in more ‘safe’ appointments. ‘There’s a danger that intellectual and political diversity is being reduced,’ he says. ‘There’s an unwillingness to take risks.’

Any applicant who expresses an opinion at interview out of line with guidance in the Equal Treatment Bench Book (which Tettenborn has previously described as espousing a ‘particular metropolitan morality’) has ‘the chances of a snowflake in hell’ of getting the job, he says.

An academic who has more time for ‘what you hear in the Dog and Duck in Ashford than precious Islington ethics’, is, unsurprisingly, no fan of targets for an ethnically representative judiciary.

District judge Tan Ikram’s family came to the UK from Pakistan in the 1960s. Unable to afford to sit the Law Society’s course, he self-studied for the Bar Final Examination, which earned him entry to a firm of solicitors. His journey to the bench was not straightforward, but in hindsight he feels the barriers were self-imposed.

‘I just didn’t think that the judiciary was looking for people like me,’ he says. ‘There was no JAC and no initiatives to attract solicitors. I didn’t see judges of south Asian heritage on the bench.’

Yet he does not support the idea of quotas: ‘Dealing with people and the demands of workload requires a multitude of skills. Appointment must be on merit and be seen to be such. The public must have confidence that the judges are there because they were selected on the basis of being the best for the role.’

That said, he adds, more could be done in fine-tuning what ‘best’ means: ‘More also needs to be done to ensure that under-represented groups arrive at the starting line for selection with equal opportunity for appointment.’

Many senior solicitors are unaware that they are eligible to become judges. Many do not want to start at the bottom of a career ladder when they have reached the top of their profession

Alexandra Marks, deputy High Court judge

Similarly, Alexandra Marks, a deputy High Court judge and former partner at Linklaters, does not subscribe to the idea that there is a ‘female’ point of view that must be represented. ‘I realised the fallacy of that at my firm many years ago.’ Ordered to come up with maternity provisions for the partnership deed, the 12 female partners produced ideas ‘as varied any other group of a dozen people’, she relates.

Rather than targets for particular groups, she feels that more solicitor judges would do most to increase the diversity of the bench. Solicitors form a much more diverse branch of the legal profession than barristers and efforts to increase numbers of judges recruited from outside the bar are expected to lead to greater diversity overall. However the proportion of non-barrister judges across all courts has fallen by 3% since 2014, mainly due to departures.

The Justice report states that solicitors’ success rates in competition for the two key feeder roles to senior appointment – recorder and deputy High Court judge – continue to be bettered by those of barristers, sometimes by a factor of 10 or more.

‘There are lots of reasons why so few senior solicitors become judges,’ Marks says. ‘Many are still unaware that they are eligible. Many do not want to start at the bottom of a career ladder when they have reached the top of their profession.’

Some may be put off by the pay – or at least the conditions of work. Judges often work in shabby, poorly maintained buildings with little support, especially for ‘fee-paid’ judges (those who sit only 15-30 days per year). Others find their firms are unsupportive of taking time out of the office to sit, especially in blocks of one or two weeks at a time (as required for many fee-paid posts).

‘But even those who are keen to become judges are, I think, seriously disadvantaged when it comes to appointment,’ Marks says. Few of them know other solicitors who have successfully applied, so have limited scope to ‘benchmark’ themselves. Also, while there is no doubt that solicitors’ skills are highly transferable, the lack of hands-on court experience is a disadvantage.

According to Marks this is not, as is commonly thought, because advocacy skills are sought in the selection process. ‘Much more subtly, it is the understanding of the protocols, use of language, choreography of trials, and behaviour in court, which give candidates credibility and “polish”. Many solicitors feel completely at sea in that environment,’ she explains.

She encourages any solicitor interested in applying to the judiciary to become a member of the Law Society’s Solicitor Judges Division: ‘Over 300 of us who are already solicitor judges are very happy – on the basis of our own experiences – to offer support and guidance to solicitor would-be judges.’

The new Pre-Application Judicial Education Programme funded by the MoJ, and supported by the Law Society and other professional bodies, is designed to help potential applicants better understand the judge’s role and how to prepare for it.

The role of our judiciary is under closer scrutiny than ever. One point not contested by critics or supporters of the current system is that it matters greatly who is appointed to judicial posts. Arguably, it has never mattered more.

Melanie Newman is a freelance journalist

No comments yet