As the government grapples with the intellectual property rights of businesses post-Brexit, uncertainty is hitting patent activity in the courtroom, writes Marialuisa Taddia

THE LOW DOWN

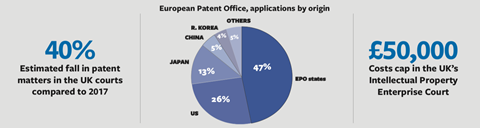

Abraham Lincoln thought intellectual property rights added ‘fuel to the fire of genius’. IP rights underwrite the value of brand, design and innovation, so it is small wonder that, in this regard, the UK government wants to enjoy the benefits of the EU’s IP regime post-Brexit. Even as it negotiates its exit, the UK is busy implementing new EU measures on trade marks, patents, design and disputes. But uncertainty is having a chilling effect on IP activity in the UK. Patent matters in the UK courts are estimated to be 40% down on the same period in 2017, while businesses that decide uncertainty means their IP must be registered and protected in both the UK and the EU 27 are bearing the extra costs of dual registration. There is a feeling among IP lawyers that ‘common sense will prevail’, but time is running short.

Brexit is top of the agenda for intellectual property lawyers. As Gordon Harris, Gowling WLG’s global co-head of IP, says: ‘The thing that is keeping us occupied, and awake at night, isn’t a development, but the fact that there hasn’t been one.’ Brexit is ‘a new product line, a new revenue generator, but one we would happily do without,’ he adds.

Intellectual property laws, including trade mark and designs, are harmonised across the EU through directives and regulations, and clients and their lawyers have benefited from this.

The UK, while extricating itself from the bloc, is seeking to remain engaged with European law and regulation. Examples include the new Trade Marks Directive 2015, which will be implemented into national law in January 2019. In April, while UK-EU talks were ongoing over the Brexit deal, the UK government committed to be part of a pan-European patent court in which the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) will have the ultimate say in questions of European law.

The world’s leading brands are among the best financial performers. ‘We know that strong brands that are protected and governed properly add value to businesses, and are a catalyst for growth,’ said Rick Sellars, creative director at Interbrand, speaking at Eversheds Sutherland’s IP branding conference in October.

But the implications of Brexit for brand owners are potentially significant because it particularly affects EU trade marks (EUTM) and registered community designs (RCDs). At present these rights are both granted by the EU Intellectual Property Office (EUIPO) in Alicante – and they cover the entire EU. On exit, they will no longer have effect in the UK. As Catherine Wolfe, a partner at Boult Wade Tennant, observes: ‘Brexit is going to have a huge impact and it is already being felt on a daily basis. The EUTM is a pan-EU right where appeals are made to the Court of Justice in Luxembourg, so it is absolutely at the sharp end of Brexit issues.’

The profession was ‘pleased’ with the draft transition terms of 19 March 2018 that ‘provided clarity and also spoke of an ongoing status quo until 31 December 2020’, Wolfe says. ‘Unfortunately, that was under the rubric of “nothing is agreed until everything is agreed”, and the political climate has grown hotter since then.’

In July, the UK government gave further reassurance to business that, on exit, existing EUTMs and RCDs will be ‘cloned’ into equivalent UK rights ‘automatically and for free’. This was reiterated in the technical guidance issued by the Department for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy (BEIS) in September. ‘This provides great comfort for the majority of cases – [as] there are many more registrations than pending applications,’ Wolfe says.

Also reassuring is the special nine-month priority period from the date of exit for pending EUTM and RCD applications to file for the same protections in the UK.

‘However, we still have no guidance in relation to ongoing contentious issues at the EUIPO, such as revocations, invalidations and oppositions. Possibly, contentious issues will be allowed to remain at the EUIPO until they are completed, but this is not certain,’ Wolfe says. ‘For this reason many are now choosing to file in parallel at the UK Intellectual Property Office (UKIPO) and at the EUIPO, because that is the only step available to be Brexit-proof. As the soonest possible Brexit date of 29 March 2019 approaches, that becomes increasingly attractive.’

As a result, Wolfe and other trade mark practitioners have been very busy. As British businesses seek pan-EU trade mark protection before Brexit, there are ‘many more filings than usual, and as a corollary there have been more oppositions’.

Peter Brownlow, partner in the IP group at Bird & Bird in London, says: ‘If we have a deal, everything will stay as it is until the end of 2020, so there will be quite a long time to deal with things. But if there is no deal, everything will happen on the 29 March, and it is not a very long way off. We have been telling our clients that they should file both a [EU] and UK trade mark,’ which the firm does at a discount, Brownlow says.

Brexit has potentially significant implications for the so-called ‘exhaustion’ of IP rights – be they patent, trade mark or copyright – whereby right-holders are prevented from restricting the sale of goods that have been placed on the market in the European Economic Area without their consent. The UK is currently part of a regional EEA exhaustion scheme, and rights are considered ‘exhausted’ once they have been put on the market anywhere in region with the rights-holder’s permission. If the UK leaves the EU without joining the EEA, the doctrine will cease to apply in the UK.

According to BEIS technical papers setting out the contingency plans for a no-Brexit deal on 24 September: ‘The UK will continue to recognise the regional exhaustion regime from exit day to provide continuity in the immediate term for businesses and consumers’ and so there will be ‘no change to the rules affecting imports of goods into the UK’. This means that ‘parallel imports’ of goods, such as pharmaceuticals, can continue from the EEA (parallel imports are non-counterfeit goods which are imported into a country where their IP rights have already been ‘exhausted’).

SHOPPING AROUND FOR A FLUID EXPERIENCE

Businesses can have three-dimensional trade marks, following a recent judgment from the Court of Justice of the European Union. The court found that a retail store layout is registrable provided the representation is capable of distinguishing the goods or services of one undertaking from those of another, particularly when the layout of the store departs significantly from the norm or customs of the economic sector concerned, Eversheds Sutherland’s principal associate Kate Ellis told the firm’s 2018 IP branding conference.

‘As a retailer, you can use your store layout as a consumer experience,’ she said. The ruling followed a reference from the German federal patent court in the Apple Inc. v Deutsches Patent-und Markenamt (the country’s patent and trade mark office) registry proceedings. But it remains to be tested whether or not Apple can enforce the trade mark registration of the layout against others.

A growing use of ‘fluid’ trade marks – whereby brands are recasting their static logos with different colours and moving shapes to establish a ‘two-way conversation’ with consumers – is also prompting new approaches to trade mark registrations. Take Absolut’s various bottles or Google’s constantly changing doodles. Ellis’ advice to brand owners is to ensure they ‘register the underlying key variants’ of the mark.

Trade marks are being used as a tool to direct traffic to websites and as a result they have become much more valuable business assets than they were, say, 20 years ago, says Peter Brownlow of Bird & Bird. One consequence is the rise in litigation around ‘co-existence agreements’ between two trade mark owners who agree to use similar marks, but subject to limitations such as different geographic areas.

But BEIS warns: ‘There may be restrictions on the parallel import of goods from the UK to the EEA’ – which means that businesses would need to check with EU right-holders if consent is needed.

‘Any goods first put on the market in the UK will not be able to be exported to Europe without the trade mark owner’s permission so that will affect distribution agreements, supply chains and retailers as well,’ Brownlow warns.

As a rule, infringement of an EUTM entitles the owner to remedies across the whole EU but, Brownlow says: ‘The UK courts will no longer have jurisdiction over any infringements happening outside the UK in the EU, and so you won’t be able to get a pan-European injunction anymore.’

He adds: ‘If someone is infringing your trade mark in a number of member states, one of which is the UK, you will have to bring two actions – one covering the new EU and one covering the UK.’

But UK courts are already adapting to the needs of users. Take the Intellectual Property Enterprise Court (IPEC), whose multi-track has a limit on damages of up to £500,000, and where costs are capped at £50,000 and hearings are limited to two days. ‘They won’t have any disclosure unless it is specifically ordered, and there will be no cross-examination. It is a very streamlined and quick procedure and very well managed,’ Brownlow says. The High Court’s Shorter Trials Scheme (STS) became permanent from 1 October 2018 in the business and property courts nationwide (cases are heard within 10 months of the date of issue of the proceedings and judgments are handed down within six weeks of the hearing), he points out. STS deals with the next level up before litigants reach the High Court.

‘We are seeing the UK, as a forum for enforcement, becoming more competitive and offering a lot more flexibility than you would get if you went to other European jurisdictions,’ Brownlow adds.

Even as withdrawal discussions continue, new EU law continues to shape the regulatory environment for IP.

Under the Trade Marks Act 1994, to be registered a trade mark must be capable of graphical representation. Since last October this is no longer a requirement, which is good news for non-traditional trade marks such as colours and sounds. These and other reforms come from the EU in the shape of a new trade mark regulation, in force since last October, and the 2015 Trade Marks Directive, which member states must implement by 14 January 2019. Despite Brexit, the UK government has said that it will implement the directive.

In a notice issued in September, BEIS claimed ‘only a few areas’ of UK patent law derive from EU legislation. And indeed IP experts say patents will be ‘generally unaffected’ by Brexit. European patents are granted by the Munich-based European Patent Office (EPO) which is ‘not an EU institution’, Rupert Bent, a partner in the IP and media group at Eversheds Sutherland, explains. The 1973 European Patent Convention (EPC), which created the EPO and governs patent laws across Europe, sits outside the EU. It includes non-EU members such as Switzerland, Turkey and Norway. As Bent puts it: ‘The EPO creates a single grant procedure such that once a patent is granted by the EPO it is effectively converted into a bundle of national patents.’ Therefore an EPO-granted patent that is effective in the UK now will be valid post-Brexit, he said.

But further complications surround the implementation of the unitary patent, and the Unified Patent Court (UPC) which was due to start at beginning of 2017 (see p6, News). This could lead the UK to withdraw from a pan-European system that will allow businesses to use a single patent (rather than a basket of national patents) and a single court to protect their rights, similarly to EU trade marks and community designs.

The UPC enjoys wide support among business and lawyers. In February, Law Society president Joe Egan wrote to IP minister Sam Gyimah to urge the government to ratify the UPC agreement, or UPCA, and in April the government did so. The UKIPO said: ‘The unique nature of the proposed court means that the UK’s future relationship with the Unified Patent Court will be subject to negotiation with European partners as we leave the EU.’

The court is an odd creature in that the agreement to establish it is governed by the EPC, a non-EU treaty. Yet it is not open to states outside the EU (25 EU countries have signed it; Spain, Croatia and Poland have not). Furthermore, the unitary patent system is established by EU regulations. Therefore, as Harris puts it: ‘The UPCA is an agreement under the aegis of the EU.’ In fact, article 21 of the agreement says: ‘Decisions of the Court of Justice of the European Union shall be binding on the court.’

As Harris notes: ‘It is going to be highly problematic because the ultimate court of appeal for issues arising out of the unified patents is going to be the CJEU.’

In September, BEIS said the UK will have to ‘explore whether it would be possible to remain within the Unified Patent Court and unitary patent systems in a “no-deal” scenario’. But that was in September, and at the time of writing the government claims it is close to a deal, and that there could be a longer transition period. With those opposing such an extension drawn from across the political spectrum, this is in doubt.

Lawyers believe that pragmatism will likely prevail, not least because one of the most important divisions of the UPC – which will handle pharmaceutical and life sciences disputes – will be housed in London’s Aldgate Tower. The start of the new system is now expected at the end of next year, according to EPO, pending ratification by Germany, which has been held up by a court challenge. So it is likely that UPC will come into force during the transition period, Bent says, giving the UK time to renegotiate its participation in it, as the agreement was signed in February 2013, well before the Brexit vote.

About two-thirds of patent trials in the UK concern life sciences, Harris estimates. ‘I have absolutely no doubts that if the UPC goes [ahead] and we remain part of it, the UK profession in its widest sense will do very well.’ For now, the participation (or not) of the UK in the new system ‘is causing an enormous degree of uncertainty’, and the number of patent matters filed in the UK courts has dropped by about 40% so far this year, he estimates.

With a full-blown patent action in the High Court likely to cost over £1m, businesses are ‘hanging on in the hope that the new court does open its doors so that they can use that,’ Harris says. It will be cheaper for businesses as they will be able to enforce patents through a single court.

Another example of the UK at the same time distancing itself from and yet becoming closer to Europe is the Supreme Court judgment in Eli Lilly and Company v Actavis UK Limited and Others [2017] UKSC 48.

‘It has introduced a concept very familiar to American and European lawyers, but new to the UK, called the doctrine of equivalents,’ Harris says. This means patents can be infringed not just by adopting a literal reading of the words of the patent claim (which sets out the scope of the legal protection granted by the patent) but ‘by items which are effectively equivalent, doing the same thing, albeit by slightly different means’.

The judgment has made a ‘big difference’ to the way Harris’ firm advises clients and to some ongoing cases. It has also introduced the need to review ‘freedom to operate’ opinions, ‘where a client comes to you and says, am I okay to do this?’ That means testing a possible infringement of another party’s patent.

During the referendum campaign, those arguing for a ‘leave’ vote insisted the UK could retain many benefits of EU membership post-Brexit. In intellectual property, that argument is about to be tested.

Marialuisa Taddia is a freelance journalist

1 Reader's comment