A clutch of ‘gig economy’ cases and the abolition of tribunal fees are keeping employment lawyers busier than ever. But the civil justice system is struggling to cope, hears Marialuisa Taddia

THE LOW DOWN

Employment tribunal claims have soared in the 13 months since the Supreme Court declared the fees payable by claimants for lodging claims and having them heard unlawful. But the benefits of this landmark judgment have been stymied by the severe shortage of judges and administration staff in employment tribunals. Solicitors tell of tribunal phones ringing off the hook and judges emailing determinations on Sunday evenings. Despite the bottlenecks, the end of the fee regime has been a major boost to employment lawyers acting for respondents. In addition, a series of ‘gig economy’ cases is prompting employers to rethink their business models – bringing serious legal headaches. But the biggest change of all could be Jeremy Corbyn reaching 10 Downing Street.

Demand for employment law advice has bounced back, fuelled by the reinstatement of free access to employment tribunals and the ‘gig economy’.

Fees for lodging claims and first substantive hearings were introduced in July 2013. But in a landmark judgment four years later – backing a claim by trade union Unison – the Supreme Court declared the charges to be unlawful and quashed the Fees Order.

The court further ruled that the fees were indirectly discriminatory on the basis that they placed women at a particular disadvantage, since a higher proportion of women would bring discrimination cases. Sex discrimination cases fell by 83% in the year following the introduction of fees.

Fees led to a dramatic decline in claims – the number of single cases received per quarter was 68% lower between October 2013 and June 2017 than in the year to June 2013; the average number of multiple cases received per quarter also fell (by 75%) over the same period.

Referring to the impact fees had on legal practice, James Davies, divisional managing partner of Lewis Silkin, says: ‘Like many other firms, we continued to grow, but we grew at a much smaller rate than we had previously or are doing now.’

Since the Supreme Court’s ruling the number of claims has soared. Statistics for January to March show a 118% rise in single employment tribunal claims compared with the same quarter in 2017. After the introduction of fees, the average number of single claims was 4,300 per quarter, but since these were scrapped single claim receipts more than doubled to 9,252 in January-March 2018.

‘We haven’t quite seen the full impact of that because the tribunal system is not set up to deal with the increased number of cases,’ Davies stresses, referring to ‘very significant backlogs in the tribunals’. Indeed, the level of claims is not back to pre-July 2013 levels: in the year to June 2013, the tribunals received, on average, just under 13,500 single cases per quarter.

The impact of scrapping fees on solicitors depends on the type of client. Richard Nicolle, a partner at Stewarts specialising in high-value and complex disputes, says: ‘From our perspective, the fees were never really a major impediment to work. We tend to act for senior execs, bankers and lawyers so fees were never really an issue.’

Nicolle argues that claimant solicitors at the lower end of the spectrum are unlikely to be affected much either, since many individuals for whom the fees would be a deterrent are litigants in person: ‘For those firms who predominantly act for respondents, of course, their clients will be having a lot more claims because lower-value employees will now be bringing claims they wouldn’t otherwise have done on relatively small sums.’

James Williams, partner in the employment and pension teams at Hill Dickinson, says that in sectors such as hospitality and retail, where the type and monetary value of claims reflect relatively low wages, ‘those claims fell away to pretty much nil – but they are now back. If you are a bartender and you are not paid your wages, worth a few hundred pounds, it is now worth bringing that type of claim, whereas it wasn’t probably worth the bother if you had to stump up fees to start the proceedings’.

Hence the necessity ‘to find cost-effective solutions to deal with the smaller cases that are coming back; you need different business models,’ Davies says. Like other City firms, Lewis Silkin acts predominantly for employers. Davies points to the firm’s low-cost centre in Cardiff and rockhopper, a low-cost, fixed-fee HR and employment law service for respondents, which is provided by a team of lawyers primarily working from home.

Launched four years ago, about the time when the fees were introduced, ‘it was pretty slow to take off, because of low demand’, Davies explains. ‘But now there is a dramatic increase in demand from clients as bigger companies want a cost-effective way to do their tribunal cases.’

There have been other benefits from the abolition of fees. With the dramatic reduction in claims, particularly at the smaller end, it had become difficult for newly qualified and junior lawyers to acquire the necessary skills and experience.

Those junior lawyers cut their teeth in an understaffed tribunal system that is struggling to cope with the surge in claims. ‘The biggest impact [the scrapping of fees] has had is on the management of cases,’ says Jon Heuvel, employment and discrimination partner at Shakespeare Martineau. ‘The tribunal process has slowed down dramatically.’

As Kayleigh Leonie, an employment solicitor at start-up TandonHildebrand explains, the reduction in claims led to a similar reduction in staff within the ET. Judges were reallocated to other branches of the civil judiciary and those who retired were not replaced. ‘The problem is that you still have the same level of resources but the claims have absolutely skyrocketed,’ she says. Outstanding caseload increased by 89% in January to March compared with the same quarter in 2017.

Leonie adds: ‘Some tribunals don’t even answer the telephone. Urgent applications are taking weeks. In some circumstances they are not even being dealt with before the matter gets to a final hearing.’

Nicolle notes that tribunal staff are working longer hours to plug the gap. He recently received an email with a notice of dismissal of claim on a Sunday evening.

Yet across the board, few employment lawyers bemoan the Supreme Court’s decision. ‘Notwithstanding the fact that we are predominantly a respondent firm, it’s probably the right result,’ says Williams. ‘When the fees were introduced, the success rate of claimants remained pretty much constant. It just went to show that it wasn’t deterring vexatious litigants, which was its purpose; and it wasn’t really raising very much revenue for the tribunal service, which again was another rationale. All it really did was act as an obstacle to justice.’

The government has committed to refund people who paid fees. Between October 2017, when the refund scheme was launched, and 31 March 2018, the government paid out £6.6m of the £33m owed.

Gig economy

Williams says ‘the era of substantial changes to employment law on an annual basis has long since passed’ and that recent changes have derived from judgments of either the Supreme Court or the Employment Appeal Tribunal (EAT).

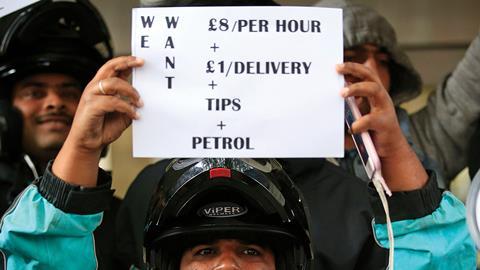

That is especially true of cases relating to the ‘gig economy’. Last November the EAT upheld an employment tribunal ruling that classifies Uber’s drivers as workers rather than self-employed – meaning that they should be entitled to holiday pay, rest breaks, the minimum wage and protection from discrimination. Uber has since appealed to the Court of Appeal with a hearing scheduled for October.

In another landmark case in June, the Supreme Court ruled that a plumber classed as self-employed was in fact a worker (Pimlico Plumbers Ltd and another (Appellants) v Smith (Respondent)); while last November the Central Arbitration Committee (CAC), the government body that deals with union recognition and collective bargaining cases, ruled that Deliveroo’s riders are not workers, but self-employed, meaning that they did not have a right to collective bargaining with the company. However, in June the High Court gave the Independent Workers Union of Great Britain permission for a judicial review of the CAC decision.

Heuvel observes: ‘It’s that whole shift around the changing facet of what a traditional employee looks like which is exercising businesses. They are struggling to work out contractually how to engage with people, procedurally how to deal with terminations, and financially what to pay people. It is resulting in litigation because of the uncertainty.’

As the law plays catch-up, Williams identifies ‘a clear incentive for those working in the gig economy on contracts that presume [them] to be self-employed to bring these types of claim, because there is a significant reward for them if there is a finding, for example, that they are entitled to holiday pay’. Williams notes that it is not just a question of determining individuals’ employment status, but also how they are taxed – whether under PAYE or as self-employed.

‘One would expect there to be at some stage a joined-up set of regulations that deal not only with workers’ rights and employees’ rights, but also with taxation,’ he adds.

HIRING SPREE

In response to a swelling caseload in employment tribunals, the Judicial Appointments Commission (JAC) is seeking 54 salaried judges across England and Wales. A recruitment campaign, the first in more than five years, was launched on 18 June and closed on 2 July.

Candidates were eligible to apply if they had five years’ post-qualification legal experience, including as a solicitor or barrister of England and Wales, or as a fellow of the Chartered Institute of Legal Executives.

Shakespeare Martineau partner Jon Heuvel describes the judicial hiring spree as ‘the largest ever invitation for salaried judges’ and argues it is ‘a unique situation’ in that for the first time the lord chancellor has opened the role to candidates without previous judicial experience. Employment judges may be appointed on a salaried (full-time or part-time) or fee-paid basis. The usual route to becoming a salaried judge was to be a fee-paid judge first but to fill vacancies the JAC had to cast its net wider.

The full-time-equivalent salary will be £108,171, plus a £4,000 top up ‘salary lead’ and allowance for London-based judges. Part-time options are available – at a minimum of 50% in blocks of at least four weeks at a time. Part-weeks won’t be possible ‘due to the length and complexity of cases’.

Heuvel highlights the growing number of cases concerning the inclusion of overtime, commission and bonus in the holiday pay of employees or workers who work irregular hours. The EAT’s decision in March in Brazel v The Harpur Trust involved a part-time music teacher who worked term-time only on a zero-hours contract; the EAT confirmed that the established practice of paying 12.07% of annualised hours as holiday pay is not always the correct method, and that it may need to be calculated differently. ‘People who have term-time employees are now panicking about the impact of this particular case,’ Heuvel says.

The EU General Data Protection Regulation has also kept employers and their trusted legal advisers occupied – for example, Lewis Silkin has a specialist team which handles workplace data privacy issues, including cross-border data flows; background checks and vetting; and complaints to the Information Commissioner’s Office.

Mandatory gender pay gap reporting, introduced in April last year for organisations with more than 250 staff, is also generating instructions. ‘It requires a lot of work with employers,’ Davies says, to help them identify and tackle any pay inequalities. Firms have also cottoned on to the ‘Me Too’ international movement against sexual harassment and assault, particularly in the workplace. Lewis Silkin has launched a service, ‘#aLastingChange’, which is designed to raise awareness of women’s workplace issues, such as sexual harassment, dress codes, maternity leave and return. The aim is to help clients ‘implement procedures to ensure they have the right model for the workforce of today’, Davies says.

‘Employers’ responses have changed,’ he adds. Whereas in the past they would try ‘to get rid of the problem now they want to find out what happened, and work out how they can do something about it’.

Brand awareness and social media play a big role in these and other developments in employment law. ‘The ability to communicate widely and quickly has changed things. Employers’ first concern is managing the reputational damage from issues that arise in the workplace and less “oh we are going to face a legal claim and how much is it going to cost us”,’ says Davies.

What about Brexit? The UK is already among the lowest-ranked Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development countries on employment protection legislation.

For this reason, Davies says, there is not ‘a huge appetite for significant change in employment law. There may be tweaks at the margins – [for example to the Agency Workers Regulations, Working Time Regulations and TUPE] – but whatever happens I don’t think employment law will fundamentally change.’

Nicolle points out there is a question over pursuing appeals against Supreme Court decisions to the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU). According to July’s Brexit white paper, there is ‘a commitment that UK courts would pay due regard to EU case law in only those areas where the UK continued to apply a common rulebook’; and it acknowledges the ‘role of the [CJEU] as the interpreter of EU rules’.

Davies, though, identifies a bigger event for employment lawyers, if it comes to pass. ‘Jeremy Corbyn is more likely to have a significant impact on employment law than Brexit,’ he points out. ‘I am not saying for good or for bad. There is likely to be a much greater priority given to collective employment rights which is going back to the pre-Thatcher days.’

Marialuisa Taddia is a freelance journalist

No comments yet