The desire to look after, grow and ultimately pass on hard-earned assets is just as strong whether you have millions in the bank or only a small nest egg – and that puts private client practitioners centre stage. While Brexit and the snap general election have caused a hiatus in estate planning for high-net-worth international clients, and battles over wills are making headlines, other issues such as coping with mental incapacity and protecting digital assets after death apply to everyone.

So how are practitioners responding to the challenges – and what are the career prospects in a practice area that touches on the most critical stages of our lives?

This year is the 20th anniversary of the Law Society’s Private Client Section, which will be celebrated at its annual conference on 30 June. The keynote speaker is Baroness Butler-Sloss, who will consider how proposed changes in the law might affect assisted dying over the next five to 10 years.

This is an important milestone for the section, which has grown to more than 2,000 members, ranging from sole practitioners focusing in their region on wills, probate and lasting powers of attorney, to those working internationally in wealth management and estate planning for the super-rich.

While some clients come in and make wills and you never see them again, you develop very longstanding and satisfying relationships with others as you help them and their family.

Gary Rycroft, Joseph A Jones & Co

So what does ‘private client’ actually mean? The key cornerstones are: wills, probate, tax planning, elderly client, trusts, mental capacity and estate administration.

‘We have always wrestled with this term “private client”,’ says Gary Rycroft, chair of the section’s advisory committee. ‘We started life as the probate section but that was never satisfactory as it was always about more than probate. While private client doesn’t mean anything to people in the real world, we have yet to find a term which encompasses everything in a neat way.’

Away from the glamorous world of successful entrepreneurs, high-profile sports people and celebrities, private client work can seem like the ‘dusty end’ of the law – but you would be very much mistaken, Rycroft says.

A partner at Lancaster high street practice Joseph A Jones & Co, Rycroft specialises in will drafting, trust and estate administration, lifetime planning for high-value and complex estates, and, increasingly, family inheritance disputes.

‘It’s an endlessly fascinating area of law because of the myriad ways people live their lives, with you guiding them through their trials and tribulations,’ he says. ‘That is the appeal for me. While some clients come in and make wills and you never see them again, you develop very long-standing and satisfying relationships with others as you help them and their family navigate their lives.’

Rycroft’s firm only deals with private client and property and its target market is within a 45-minute drive of the office. While there are some sizeable estates, including among the nearby farming community, most are worth less than £2m.

As an indication of private client’s breadth, it is a key sector for Withers, which has 680 lawyers, 18 offices globally and a client list of 51% of the most recent Sunday Times rich list, up from 45% last year.

‘It is a real privilege being a private client lawyer,’ says Withers partner Ceri Vokes. ‘As their trusted adviser, I am involved in both legal and non-legal issues. It may be a family matter that can better be settled as it arises rather than by excluding someone from a will, or it may be about setting up a charity or a prenup for one of their kids.’

She works mainly for new money entrepreneurs, sports people – she helped Jürgen Klopp on his move to Liverpool – charities and international families. Alongside tax and trust planning, there are issues around endorsement deals, image rights and, increasingly, digital assets.

There is the added bonus that, whatever is happening in the economy, private client work rides out the peaks and troughs because the need to plan your affairs does not stop, prompting some of the big firms that closed down their private client departments a decade or two ago to reconsider.

‘Those who stuck with private client are reaping the benefits,’ says Mishcon de Reya associate Stuart Adams, ‘with a lot of very wealthy people coming to the UK needing advice. We are very busy and expanding in both the quantity and quality of work.’

Private client work also plays a key role in the make-up of Veale Wasbrough Vizards, which has growing teams in its Bristol, London, Birmingham and Watford offices. ‘We are a full-service firm and if we didn’t offer private client services, it would leave a very big hole,’ says partner Michael Knowles.

So what are the key issues on practitioners’ desks?

On the contentious side, there has been a surge in disputes over wills, trusts and family inheritance as well as a big increase in elder financial abuse.

The case dominating the headlines this year was the decision in Ilott v The Blue Cross, the RSB and RSPCA [2017] UKSC 17 – the first time a claim under the Inheritance (Provision for Family and Dependants) Act 1975 Act went before the Supreme Court. The row centred on Melita Jackson’s decision to leave her £486,000 estate to the three charities and nothing to her estranged daughter, Heather Ilott. The judge at first instance ruled Ilott was entitled to £50,000 for the provision of reasonable maintenance. However, the Court of Appeal increased this to £143,000 to buy the property she was living in and a further £20,000 to supplement her state benefits.

The charities appealed and, after a decade of litigation, the Supreme Court ruled in their favour, saying the Court of Appeal had erred in its application of the law and reinstating the original £50,000 award.

The case prompted some ‘extremely hysterical’ headlines about the principle of testamentary freedom, says Professor Lesley King, a consultant with the University of Law who writes on wills and probate for the Gazette.

Traditionally, people have seen tax avoidance as legal and tax evasion as illegal, But there is now a moral dimension to consider. What was previously seen as legitimate planning to reduce the amount of tax payable is now seen as anti-social.

Ceri Vokes, Withers

However, the judgment itself was a ‘bit wishy-washy’, she says, and did not give any real guidance to trial judges trying to weigh the competing claims of charities and family members.

‘In a sense it couldn’t,’ she asserts, ‘because every case is different and different factors apply. However, the court acknowledged that, while charities don’t have “needs” in the way individuals do, they are dependent on their legacy income to carry out their purposes which are for the public benefit. So, if they are the chosen beneficiaries of the testator, those bequests should not lightly be set aside.’

So what advice should practitioners now give family members or charities when a will is in dispute? ‘It’s very hard,’ she says. ‘All you can do is form your own value judgement and go for the strengths of your case and hope the trial judge takes the same view.

‘The Supreme Court decision absolutely won’t stop these cases. What it might stop are the appeals. The court made it clear that, because the trial judge has to make a value judgment on the competing claims, an appellant court shouldn’t interfere with that decision unless the judge has got it completely wrong.’

Roman Kubiak is head of the contested wills, trusts and estates department at Cardiff firm Hugh James. His team has doubled in size to six since he joined five years ago and he is looking to recruit.

‘There has been a huge rise in enquiries from five or 10 a month five years ago to around 50 a month,’ he says. ‘They cover a broad spectrum, from our bread-and-butter will and Inheritance Act disputes to a growing number of disputes around trust administration and lifetime disputes over powers of attorney or deputyships.’

He highlights a significant change around the question of testamentary capacity: ‘With an aging population, cognitive impairment is an issue. But advances in science and medicine have made it possible to assist people in making decisions, so courts are increasingly loath to set aside wills on the basis of the testator’s lack of capacity.

‘Instead, they are favouring setting aside wills on the grounds that the person didn’t know or approve it. The Mental Capacity Act has played a huge part in this.’ Kubiak is also seeing in Court of Protection cases judges starting to shy away from the general rule that the protected party (‘P’) pays the costs of an action. It is a useful message, he says, that there is no ‘carte blanche’ to use P’s assets to fund a family feud.

He highlights other key cases of 2017, including Roberts v Fresco [2017] EWHC 283, which confirms that claims under the 1975 act cannot be continued by relatives after the claimant’s death; and Patel v Patel [2017] EWHC 133, which flags up the forensic routes available to practitioners who suspect a will has been forged.

The recent unreported decision in British Red Cross and others v Werry and others should also act, he says, as a reminder to practitioners that, in certain cases, a settlement or order can be set aside on the contractual principle of common mistake.

With so many disputes, Kubiak is seeing mediation playing an increasingly important role. While some clients and practitioners remain ‘sceptical’, he is a ‘big fan because it often achieves a far quicker resolution as well as saving financial and emotional costs’.

On the non-contentious front, practitioners have had their hands full with the uncertainty around Brexit, the proposed probate fee hike, fiendishly complicated calculations around the new residence nil-rate band (RNRB), changes to ‘non-dom’ status and new EU anti-money laundering regulations.

The Private Client Section held a cross-border conference in March. Adams, a member of the section’s advisory committee, says one issue for practitioners here concerns Brussels lV. This rule effectively says that, where clients are UK nationals and resident here, they can elect that UK law will apply in relation to the succession of assets, such as a holiday home, rather than local law.

‘I don’t think this will be undone by Brexit,’ he says. ‘We never signed up to the legislation but it will remain in force. It may still be advisable to make wills in the different jurisdictions. But consideration should be given to incorporating this special election because Spain, for instance, which did sign up to the legislation, will still have to recognise the wishes of an English will.’

Generally, practitioners say Brexit has created more work as clients worry how it will affect them.

On the probate front, relief that the huge hike in fees fell away with the snap general election is tempered by a belief that the proposal will come back – though probably on a sliding scale rather than as an ‘invidious stealth tax’, Rycroft says.

It had led to clients rushing through their probate applications to beat the May deadline, he says, and risked sparking aggressive selling of lifetime trust arrangements by the unregulated market.

Practitioners have also been having to get to grips with the new RNRB, which came into effect on 6 April.

‘Clients want you to predict what will happen but it is so hard to tell,’ Knowles cautions. ‘Catering for the possibility that someone might want to downsize or move to a nursing home, for instance, involves incredibly complicated calculations. It will have to be simplified whoever gets in after the election.’

Alongside national changes are global pressures to increase transparency and regulatory compliance and crack down on anything that smacks of tax evasion.

The chancellor announced in the March budget that advisers could face fines of up to 100% of the tax their client avoided if an HMRC investigation finds the scheme they helped create falls foul of the rules.

‘In a practice like ours,’ Adams says, ‘we don’t do racy schemes that sail close to the wind. But those who do stretch things may change the way they advise clients.’

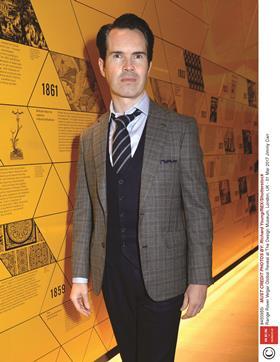

For the last three or four years, Vokes says, clients have been more worried about the reputational implications of being caught up in a tax scandal, having watched comedian Jimmy Carr (pictured) and singer Gary Barlow strung up by national newspapers.

‘Traditionally, people have seen tax avoidance as legal and tax evasion as illegal,’ she says. ‘But there is now a moral dimension to consider. What was previously seen as legitimate planning to reduce the amount of tax payable is now seen as anti-social.’

Over the summer, HMRC is putting in place online reporting facilities to meet the requirements of the fourth EU Anti-Money Laundering Directive to register not just the settlors and trustees of a trust with tax consequences but also the beneficiaries.

The furore over the leaking of the Panama Papers prompted proposals that these registers should be open to anyone who can demonstrate a legitimate interest, such as an investigative journalist, to improve transparency.

However, King says practitioners should ‘give a vote of thanks’ to the European data protection supervisor who issued an opinion in February strongly criticising the proposed amendment. ‘This made the point,’ she says, ‘that the amendment was disproportionate and contrary to the general principles of data protection that you can’t arbitrarily use information provided for one purpose for another.’

DON’T LET YOUR DIGITAL LEGACY CRASH

It is no longer enough to plan who will get your car, house or savings after your death – what happens to your Facebook profile, the thousands of photographs held in the cloud, the money in your eBay or PayPal accounts, your online share portfolio?

With so much of our professional and personal lives now conducted online, Ian Bond (pictured), head of trusts and estates at Black Country firm Talbots, says it is vital practitioners discuss with clients what should happen to their digital estate.

With the Wills Act dating back to the first year of Queen Victoria’s reign and the Administration of Estates Act to 1925, Bond says the current law does not provide the necessary guidance and structure to address digital assets.

He has been involved in drawing up guidance which will be published by the Law Society this summer. He says practitioners must keep pace with technological and encryption developments so they can help clients who want to die ‘tidily’ identify who actually owns any digital assets and ensure the right people have access.

There is no single definition of a digital asset, says Bond, who would include in the list crypto currencies, such as bitcoins, cloud storage, digital music, videos and photos, social media accounts, email accounts, domain names and websites, gaming accounts including avatars, and blogs.

While some may be very valuable – a bitcoin or an avatar can be worth thousands – it may be that the sentimental value of others is of even greater importance. Ownership has also changed, as a famous actor reportedly found when he wanted to pass on his huge iTunes library and discovered it was only licensed to him during his lifetime.

So, what happens if someone dies and their devices cannot be accessed or there is no paper trail of bank statements or share certificates? How far does the practitioner’s duty go in trying to trace the deceased’s digital assets, because they could face potential negligence challenges by beneficiaries if something is missed?

Bond says practitioners need to educate their clients at the will-making stage to set up legacy contacts with Facebook and Google (for example) so a named person can access their accounts after their death.

Clients also need to compile a digital assets log, stored safely so it does not become a goldmine for fraudsters.

However, issues may still arise because digital assets are often held on shared servers, with providers in a different country storing data in many jurisdictions. It may be unclear whose laws will apply, leaving each provider sitting in final judgement on the fate of the assets.

Bond also flags up the risk that family members who do know online account details could transfer money before notifying anyone of the person’s death to avoid probate fees or inheritance tax.

He says practitioners should advise clients that they might be committing an offence under the Computer Misuse Act if they do and, if practitioners are concerned about any behaviour, they may need to protect themselves by making a suspicious activity report to the National Crime Agency.

The key, he stresses, is to check what is stored on any device or in the cloud before passing it on to a beneficiary.

Bond looked after the estate of Empire of the Sun author JG Ballard. ‘We were given his laptop by his family,’ he recalls. ‘When we searched it, we found two unpublished manuscripts which were later published in an anthology, creating royalties for his beneficiaries. While not everyone is JG Ballard, you never know what might be on someone’s devices.’

What is clear, says Bond, is ‘we don’t yet have the right answers. We need to highlight best practice so the more people share stories and problems, the more we can all learn’.

On a broader note, private client lawyers are increasingly having to deal with issues around capacity, prompting the Law Society to develop an accreditation scheme for those involved in health and welfare issues under the Mental Health Act 2005.

It is also prompting some innovative ideas. Philip Goldberg is managing director of Leeds-based Minton Morrill, whose Court of Protection team looks after clients who have come to them through a clinical negligence claim. ‘We must see our clients once a year,’ he says, ‘so we are using Skype and webcams to keep costs down for clients. This is not about taking detailed instructions but assessing that their needs are being catered for. Our clients find it novel and engaging. We could even buy someone an iPad just for this purpose which would still save money because of travel costs.’

Society unveils accreditation scheme

Applications open this August for the Law Society’s new Mental Capacity (Welfare) Accreditation, which is designed to ensure vulnerable people have access to expert independent representation in court hearings. Solicitors, barristers and chartered legal executives who advise on health and welfare matters under the Mental Capacity Act 2005 can apply to be either an accredited legal representative (ALR) or an accredited practitioner.

Rachel Hawkins, the Law Society’s product manager responsible for accreditations, says that, while both are recognition of the practitioner’s expertise, only ALRs can be appointed by the court to represent a protected party in court.

The first step, she explains, is a mandatory two-day training course provided by City Law School, which will cover black letter law through case study work. It will also cover the Court of Protection (Amendment) Rules 2015 and the impact of the Transparency and Case Management pilots on daily practice.

The next step is to submit the application form, which will be followed by an interview; a case study to test knowledge and experience of health and welfare matters; and for ALRs, a further assessment to provide feedback on a mock client interview. Reaccreditation is required every three years.

More information can be found on the Law Society website

With so much on the agenda, what are the career prospects like?

Withers recruits around 11 trainees across the firm, with four in private client. Vokes, who doubles up as training partner, says the firm will also be launching a solicitor apprenticeship scheme in September for school-leavers.

The opportunity for progress is wide, she says, with a good work/life balance. With three children under seven, she works fixed hours – ‘I walk out of the door at 5pm’ – and one day a week from home and keeps clients happy by working when her children are in bed.

However, Rycroft is concerned that, away from the bright lights, aspiring lawyers are not coming into private client work. ‘There is a real issue on the horizon in terms of skills,’ he says. ‘Some big hitters are retiring in our region and I am not sure the next generation is coming up who have the same knowledge. But that does open up some real opportunities.’

Knowles says some other practice areas may appear ‘more glamorous – if they mean staying up all night at meetings, I am quite happy not to have to do that’.

But having a good work/life balance comes at a price. ‘You might not make the headlines in terms of highest-earning lawyers but it is a profitable area of law for firms so you should be remunerated appropriately,’ he says.

And the pay-off for your hard work? ‘You develop highly transferable skills and, if you fancy retiring to the West Country, you can carry on working there much more easily than if you are an international corporate lawyer.’

For more details, please go to the Law Society Private Client Section.

Grania Langdon-Down is a freelance journalist

No comments yet