Earlier this month, I was privileged to attend CodeX – the Stanford Center for Legal Informatics – FutureLaw Conference at Stanford Law School. As David Curle, director of market intelligence at Thomson Reuters Legal, wrote in his report of the event: ‘CodeX FutureLaw is one of the few places where the lawyers and the technologists can meet and get excited about innovation’ (see tinyurl.com/kb623ar).

Participants and attendees included legal IT luminaries from across the profession, corporate legal departments, law schools and technology businesses.

The keynote speech by Professor Gillian Hadfield of USC Gould School of Law covered the principles for reinventing law in her book, Rules for a Flat World. Why does law need reinventing? Because at the top end of the market 70% of corporate clients do not recommend their primary law firm; and at the bottom end of the scale, legal services are too complex and expensive for ordinary people to access. Professor Hadfield offered five steps to change:

- Change the conversation

- Don’t leave it to the lawyers

- Change the rules

- Catalyse and fund research

- Invest in legal innovation

As Curle observed, FutureLaw’s central theme was ‘don’t leave it to the lawyers’. Technologists, process engineers, data scientists, government and professional bodies, corporate institutions and law schools need to be involved in providing better value and broader access to legal services.

Another recurrent theme was innovation; perhaps law needs redesigning rather than reinventing.

CodeX and legal innovation

CodeX presented legal innovation as new platforms – rules-based systems and chatbots; new processes like predictive analytics and artificial intelligence (AI); and new people – providers of new legal services and technology, and future lawyers (current law students and maybe robots).

And it did not avoid the fundamental challenges. Judy Perry Martinez, chair of the American Bar Association (ABA) Presidential Commission on the Future of Legal Services, and special adviser to the ABA Center for Innovation, outlined the commission’s findings:

1. The traditional law practice business model constrains innovations that would provide greater access to, and enhance delivery of, legal services.

2. The legal profession’s resistance to change hinders additional innovations.

3. New providers of legal services are proliferating and creating additional choice for consumers and lawyers.

Unsurprisingly, given the fast-follower culture in legal IT, innovation is following the same pattern as AI. Almost every week brings media coverage showcasing another firm’s ‘innovation’ efforts which follow the same pattern: establishing an innovation department or committee and one or more innovation roles; introducing or investing in AI; and getting involved with start-ups and/or forming an alliance with a law school around legal technology training.

There are, of course, some genuine innovators: legal AI pioneers such as Berwin Leighton Paisner in the UK and BakerHostetler in the US – and new law firms and legal services providers. They develop groundbreaking products and services without the burden of legacy systems, processes or people. But the traditional partnership structure and culture is still a barrier to change. The answer perhaps is redesign rather than transformation.

Design anthropology

As design anthropologist Charles Pearson wrote: ‘Technology is cultural and all software is baked with certain values and premises’ (see tinyurl.com/l8zyblv). Paresh Kathrani, senior law lecturer at Westminster University, recently observed that law is a social endeavour and legal technology, particularly AI, needs to reflect that – perhaps by following Pearson’s example at Adobe, where he specialised in user-centric design based on ethnographic research for the Photoshop product team.

Examples of design-led legal IT include the chatbots that have previously featured on these pages. One of my CodeX highlights was Joshua Lenon’s critique of chatbots and the responses by chatbot creators Joshua Browder of DoNotPay (who is studying computer science at Stanford), Artem Goldman and Andrey Zinoviev of Visabot, and Kevin Xu of Hilbert Technologies (and a Stanford Law student), whose principal purpose was to provide legal services for those least able to access or afford them.

Lenon, who is lawyer in residence at practice management system supplier Clio, highlighted issues, including geography, choice/consequences and evidence that could ‘unintentionally deny people’s rights’. It was clear from the responses that this can be addressed by design supported by ethnographic research to improve user experience (UX). Xu focused on representing information visually – ‘start with the people, not the bot’. Browder’s DoNotPay is based on a decision tree: ‘One answer can eliminate multiple possibilities, bringing clarity to inarticulate responses.’

Although the principles of design thinking often run contrary to the legal business model – for example, it would be challenging for most corporate law firms to embrace the concept of fast failure – involving them in product development is bringing some of the benefits to legal IT.

Jan Van Hoecke, CTO at legal AI vendor RAVN, brings ethnographic research into the development process by releasing products early. ‘We give clients access to prototype versions to see how they interact with the software and adjust it in response to feedback,’ he explains. ‘We cannot do this with every law firm, but some were willing to help create and refine RAVN’s self-service module before its general release.’

‘The key is to communicate with our client base during the development process, asking them what they want and giving them an idea of what’s technically possible,’ adds CEO David Lumsden. Another critical success factor is to engage the right mix of firms and users in the product development process, particularly when it comes to legal AI which involves a variety of users across the firm.

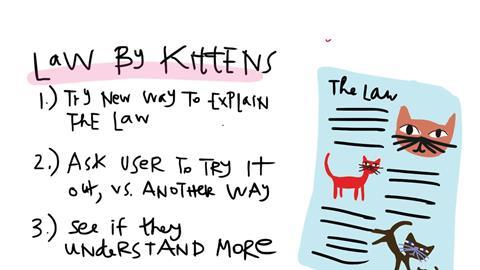

Design is even more important when the user is the client. CodeX featured an inspiring presentation by Margaret Hagan, director of Stanford Law School’s Legal Design Lab, on how design can make legal services usable, useful and engaging. Hagan explained how creating standard mark-up schema produced more effective search results and clearer, more easily navigable websites to extend access to actionable information and advice. She explained the process of combining design and ethnographic research to ‘link the folksonomy with the ontology, so the way people phrase their problems link to how providers model it’ as ‘Law By Kittens’ (above).

Rebranding death

We want to build the first consumer brand for death and cross the chasm into consumer culture in an area where people don’t want to shop around

– Dan Garrett

Farewill is an automated will-writing start-up in London. Its founder and CEO Dan Garrett trained at the Royal College of Art. He was inspired to move into legal while working as a product designer in geriatric care in Japan, when he noticed that patients at the end of their lives were uncomfortable discussing their wishes.

Garrett designed Farewill to transform our perception of death – at least the legal processes around it. He was inspired by John Maeda, global head, computational design and inclusion at Automattic: ‘Design is a solution to a problem.’ For example, Airbnb tackled the difficulty that most people are not comfortable staying in a stranger’s home by building trust into every aspect of their brand and every customer interaction, thereby changing the hospitality industry. ‘People have been writing wills online for 20 years, but there is no universal consumer brand because, before Farewill, will-writing services did not use design to overcome the perception that it is a difficult, lengthy process. We put a great effort into making our website user-friendly and we used focus groups to help us optimise the wording, the page design and the ability to move between sections. On the marketing side, our direct approach includes live chat. We don’t skirt around the issues.’

Farewill’s brand promise is a quick, cost-effective way of making arrangements around death and changing them ‘when life happens’. Garrett’s plan is not to apply the same business model to other legal services, but to supplement the will-writing service with funeral and probate services. ‘We want to build the first consumer brand for death and cross the chasm into consumer culture in an area where people don’t want to shop around,’ Garrett says. ‘To this end, we have created a bold brand and designed products that are accessible, affordable and user-friendly.’

Avoiding extinction

We give clients access to prototype versions to see how they interact with the software and adjust it in response to feedback

– Jan Van Hoecke

Mitch Kowalski’s presentation at Coventry University reiterated the powerful message in his prescient book, Avoiding Extinction: Reimagining Legal Services for the 21st Century, which features a fictional law firm run as an agile business incorporating modern management, cost-efficient processes and cutting edge technology, and embracing diversity. Kowalski presents this from two perspectives – the external reader, who is assumed to be familiar with the legal services market, and a fictional corporate client whose legal counsel is struck by the differences between this new legal business model and their traditional panel firms. Like Martinez at CodeX, Kowalski identified the traditional legal practice model as the main barrier to innovation and anticipated the need to redesign this via what he terms the ‘great legal reformation’. He reiterated Hadfield’s point that ‘lawyers are only a piece of the puzzle’ and that firms’ clients are driving the sector to change.

However, a series of online polls by Craig Webb a partner at Brethertons, who hosted the event, indicated that most firms were underprepared for the ‘great legal reformation’ in terms of investment and commitment. This led me to consider whether compartmentalising ‘innovation’ into appropriately titled departments, roles and events is the traditional law firm’s way of positioning itself as innovative in order to promote business development while avoiding the main challenge – redesigning the legal business model to address the demands of corporate clients and extend access to affordable legal services. But this is a big ask, requiring a combination of tech know-how and ethnographically supported (re)design to create/automate the right products and processes, and effective communication to drive through operational and cultural change.

The author thanks Professor Roland Vogl and his colleagues at CodeX, and David Gilroy at Conscious Solutions

1 Reader's comment