Councils have cut support for law centres and increased rents, threatening their survival just when people need their services most

The low down

Taken as a whole, the legal sector has weathered the significant challenges of Brexit and the pandemic’s restrictions well. Operational resilience has fused with the rise in clients’ legal needs that accompany any period of disruption and uncertainty. That has produced stellar financial results in the City. But disruption and uncertainty remain for another group of clients. For those who cannot pay legal fees and do not qualify for legal aid, law centres are their only hope of resolving legal problems. The level of these clients’ needs demands that this be a golden age for law centres. Instead, centres are struggling with the level of need, a fall in funding and, in some cases, the conduct of opposing parties that have deeper pockets.

Countrywide, commercial firms are flourishing despite – or perhaps because of – the pandemic. According to the Office for National Statistics, UK legal turnover in March 2021 reached an all-time monthly high of £4.06bn compared with £3.1bn in February and £3.3bn the previous March. This was reflected by stellar rewards in the City, with one magic circle firm’s profits per equity partner nudging £2m, and another paying its newly qualified lawyers £100,000 salaries.

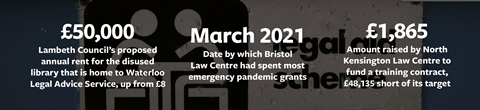

Just a few miles away to the west it is a different story. Last July the UK’s first law centre to open its doors – London’s North Kensington Law Centre – celebrated its 50th birthday. In optimistic mood, it launched a campaign to raise £50,000 to fund a training contract for an ethnic minority candidate from the local area. Today its fundraising platform records donations of just £1,865. A despondent Franck Kiangala, NKLC’s director, tells the Gazette: ‘We still have to raise £48,135 to reach the target.’

The legal sector could hardly be more polarised. To coincide with NKLC’s 50-year anniversary, the Law Centres Network issued a warning on the ‘critical threat to civil justice’ in the UK today.

We’ve got very strict cost control in place which is not necessarily sustainable. I sometimes feel it contradicts with what the client needs

Karen Bowers, Bristol Law Centre

‘The principle of equal access to justice is not reflected in the reality of the current system, which is underfunded, skewed in favour of wealthier individuals and organisations, and ill-equipped for the imminent challenges of a Covid-19 driven recession and its longer-term social impact,’ its report said.

As legal aid firms close and advice deserts expand, it is thanks to law centres and pro bono law clinics that the system is not more skewed than it is. Acting for people for whom both legal aid and privately funded representation are inaccessible, they not only increase access to justice but also help reduce numbers of litigants in person, who can make huge demands on judicial time.

Yet neither the courts nor other lawyers can be relied on to recognise that contribution, as solicitor Simon Bruce has discovered. Bruce, who works part-time as senior counsel at Farrer & Co, also works in four different pro bono law clinics in London including Dads House. He is the sole lawyer there, working with help from law students and alongside other services offered by the charity, such as a food bank. The clinic has neither scanner, photocopier nor software for automatic pagination. This makes the administration of cases more difficult than for the commercial firms which often represent the other side of the clinic’s cases. Firms’ responses to a David v Goliath situation vary, Bruce tells the Gazette.

‘I find that at least half of the law firms are civilised and appropriate with us as a law clinic and some of them are complete and utter sh*ts,’ he says.

In a recent case, his client’s husband was represented by the Liverpool office of national firm Hill Dickinson. As lawyer for the applicant, the burden of preparing bundles for the case fell on Dads House. Bruce explained to Hill Dickinson that the charity could not do so.

‘Do Hill Dickinson wish us to deploy a food bank worker for three hours to go to a copying agency, and for us to spend money donated to help the homeless, on the basis that their client, who apparently pays them thousands of pounds a month in fees, insists on our charitable funds being spent on his divorce?’ he asked. The firm declined to step in.

Bruce then wrote to the judge, who confirmed that he was responsible for the bundle.

He then had the option of coming off the record as the wife’s solicitor, leaving her as a litigant in person, or, he says, using resources from elsewhere in the clinic to produce the bundle. Instead, he wrote to the CEO of Hill Dickinson and the firm did then produce the bundle. ‘But the barrister for the husband spent half his position statement saying that the behaviour of the wife’s solicitor was outrageous,’ Bruce added. ‘I asked Hill Dickinson how long it took to produce and at what cost. They wouldn’t answer.’

The Gazette asked Hill Dickinson, whose website says it is ‘a responsible business with strong ethical standards’, to respond to Bruce’s comments but it declined to do so.

LESSONS FROM LOCKDOWN

With the help of Lottery funding, the Law Centres Network is reviewing centres’ experiences of lockdown to identify lessons for the future.

Julie Bishop (pictured), network director, says people whom Covid had impoverished for the first time in their lives placed new and different demands on the network, while many of their usual stream of users disappeared from view. When centres closed, those whose first point of contact had been in-person or via referral from third parties that had also closed, saw huge drops in clients even after they set up remote working.

‘It’s highlighted that most people come to law centres via an intermediary and the importance of being embedded locally,’ Bishop says. ‘You need to understand the local community and go to where people go.’

To let people know centres were still functioning, one put leaflets in food bank parcels, another set up a service so people could telephone it from a food bank, while others put posters in pharmacies and post offices.

Centres also learned about how to establish a trusting relationship remotely. ‘We noticed that where there was already an established relationship, transferring online was more straightforward than when the first meeting was remote,’ Bishop says. ‘And a huge lesson is the importance of funding tailored to individual needs rather than to an individual act of assistance. Legal aid won’t address the sudden loss of a job.’

Commercial law firms are not known for their willingness to be kind in litigation. Clients who have hired a lawyer in the expectation of dogged pursuit of their interests may not be happy to find them volunteering to help their opponents. But Bruce feels that profitable commercial firms such as Hill Dickinson (and judges themselves) should recognise clinics’ voluntary contribution to justice rather than sticking to the letter of the procedures when dealing with them.

‘A week before the hearing with Hill Dickinson, I was in front of a recorder who thanked me and said the whole justice system would grind to a halt if there weren’t people like me prepared to work pro bono.’

Support from the profitable commercial sector is more vital given the financial pressures on centres. Karen Bowers, chief executive of Bristol Law Centre, says most emergency pandemic grants had been spent by March 2021. ‘This year our forecast legal aid income is actually lower than last year,’ she explains. But the post-pandemic grant-funding environment is much more challenging than it was. The centre has attempted to offset this with more partnership working and triage but is still very overstretched. ‘We’ve got very strict cost control in place which is not necessarily sustainable. I sometimes feel it contradicts with what the client needs,’ she says.

In the north-east, Michael Fawole faced the same March cliff-edge problem. ‘And we have no core funding,’ he explains. The law centre he runs previously received a grant from Newcastle City Council but it was not renewed in 2021. ‘Their own grant was cut by central government and their main concern is responding to Covid,’ he says. A recent name change possibly did not help. It changed from Newcastle Law Centre to North East Law Centre to reflect the work it does across the region. ‘When we were “Newcastle” the city council felt they owed us something – now we’re everybody’s problem,’ Fawole observes.

When we were ‘Newcastle’ the city council felt they owed us something – now we’re everybody’s problem

Michael Fawole, North East Law Centre

In London, Lambeth Council is causing consternation for a long-established legal centre. South London’s Waterloo Legal Advice Service (WLAS) faces an uncertain future. Its home is a once-derelict library. In 1973 the council agreed to lease the site to a community group for a peppercorn rent. The newly formed Waterloo Action Centre then raised the huge sums necessary to restore the building. ‘We spent around £1.5m getting the whole building into active use,’ says Jenny Stiles, one of the centre’s trustees. As well as the Legal Advice Service the centre offers meeting space for other community groups and activities for the elderly.

As part of a reorganisation of voluntary sector funding, Lambeth is now proposing to hike the centre’s rent from £8 per year to £50,000, which would swallow a third of its income and force it to close or run on a more commercial basis. Lambeth is also planning to limit leases to 10 years, whereas Stiles says a term of at least 25 years is necessary to access capital grants for building works.

Rosalind Connor, one of the senior legal advisers at WLAS (as well as managing partner at Arc Pensions Law), says meeting clients in person is essential. Many do not speak English as their first language, and many have chaotic lives and complex problems that require an ongoing relationship.

‘And the centre is exactly the space we need – a big old hall in a central location with space for people to sit behind desks. Our clients are not people who can afford train fares.’ There is no way the service could fund suitable alternative premises, she says. Demand is so high that Connor asked the Gazette not to advertise the centre’s drop-in opening times. ‘As it is, we can only just cope with the number coming through the door,’ she says.

Connor knows the centre reduces pressure on the courts, noting: ‘Sometimes all we have to do is advise that the law won’t help here.’ Conversely, where someone is being treated unfairly, the service may only have to write one letter ‘which effectively says the person we’re helping knows what you’ve said isn’t true’.

Some centres go beyond the provision of legal advice to those in need and embark on litigation to challenge and change policy. Law Centre NI, whose work in Northern Ireland won not-for-profit agency of the year at the 2021 Legal Aid Lawyer of the Year Awards, is a prime example. Director Ursula O’Hare says the centre ‘knits together our legal work with advocacy to bring about social change’.

In 2020 the centre brought a judicial review of rules on benefits for the terminally ill who have a prognosis of more than six months. The centre lost at appeal but governments in Westminster and Belfast have committed to legislative change.

Kathleen Cosgrove is a housing lawyer at Greater Manchester Law Centre (GMLC). In 2020 three of GMCL’s clients instructed her to challenge the Home Office’s decision to resume evictions of asylum-seekers during the pandemic. In November 2020, she obtained an injunction prohibiting eviction of all 4,000 affected asylum seekers.

In a joint case with Deighton Pierce Glynn, she mounted a fresh and successful challenge in April 2021 when the Home Office attempted to restart evictions. The government agreed to postpone evictions until step 4 of the pandemic roadmap was reached. It also agreed to pay the centre’s costs.

In this case, Cosgrove’s clients were eligible for legal aid, but most are not, either because they are in the wrong income bracket or because their legal problem is out of scope. Again, despite the fact GMLC is often working for free, the large firms representing landlords ‘don’t do us any favours’, Cosgrove says. ‘Generally, people are collaborative but they don’t cut us any slack, we get no sympathy.’ If the civil justice system is going to continue as it is, with huge numbers of people excluded from legal aid, she feels it needs to be made more accessible. ‘It’s hard enough to navigate for those of us with legal training.’

As an example, she pointed to the forms defending against possession proceedings, which ask for detailed information about the defendant’s income. ‘But that may not be relevant – the landlord might not be bringing a claim for rent arrears,’ she says. ‘It might be that they want to sell the property, in which case the defence is that their paperwork is not in order.’

No commercial client in a comparable position would feel that they had sufficient information to mount a proper defence, Cosgrove says. ‘So why do we feel the most vulnerable should be able to navigate the system without support and assistance?’

Melanie Newman is a freelance journalist

1 Reader's comment