Last week’s Sandbox Showcase demonstrated that the best tech companies are no longer following the law firm

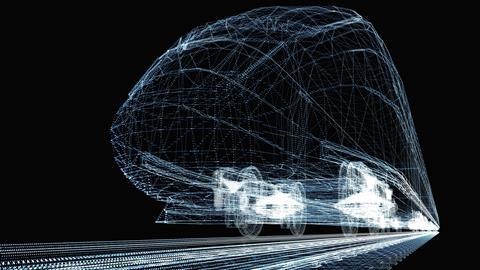

Right now, legal tech feels more like a movement than a collection of software systems and applications that underpin legal service delivery, powering the innovation dynamic that is reimagining the sector. A decade ago, it would be hard to imagine a government minister promoting lawtech. Yet at the Lawtech Sandbox Showcase, justice minister Lord Wolfson said that lawtech was no longer a nice-to-have, and if firms did not jump on the lawtech train it would leave the station anyway.

While lawtech is a critical success factor for the legal sector – in the same way as fintech is for financial services – to continue Lord Wolfson’s analogy, before you jump on a train you need to know where you are going and when you need to get there, even though your destination may change part way through the journey.

Investing in tech and innovation requires a business case, a budget, a delivery strategy and an implementation plan.

Are you starting from scratch, getting on the lawtech train at the terminus, or are you already further down the line? Are you on the fast train to digital transformation, perhaps moving core systems to the cloud, introducing automated workflows, and making strategic tech investments to open up new opportunities and markets?

Or are you venturing into new territory, developing tech products for specific practice areas or clients, incubating lawtech startups, accepting payments in cryptocurrency, or planning a virtual office in the metaverse? There are multiple destinations on the lawtech line, and the landscape is constantly changing.

Some developments are speeding up the journey, but there are also challenges which are causing significant delays. These issues are holding up progress towards fully digitalised, universally accessible, legal services, which are now the vision of effectively all the high-profile leaders and influencers in the sector.

On the fast track

One concept which promises to fast track legal documentation in (and between) multiple sectors is smarter contracts, the subject of LawtechUK and its UK Jurisdiction Taskforce (UKJT) project which launched on Tuesday. The term ‘smarter contracts’ is used to cover digital contracts which are legally binding, ranging from mainstream applications such as e-signatures, to self-executing documents that use verified immutable actions recorded on the blockchain to automatically trigger authorisations and payments. The point is that digitalised documents are to some extent executable, even to the relatively limited extent of adding a verified signature, so they cannot be a digital image of a physical document. They are more like a single-use e-ticket than a digital copy of a paper ticket.

Automation for the people

As Lawtech UK director Jenifer Swallow observed at the Sandbox Showcase, the online applications that are transforming legal services are predominantly mass-market and consumer-facing. They are not just changing legal service delivery; they are designed to address unmet legal need and change the way people buy and use legal services.

For example, the Smarter Contracts project includes a section on digitalising home buying and selling – a potential gamechanger for property transactions. I wrote about conveyancing on the blockchain in 2020, which just two years ago was groundbreaking, but unlikely to replace conventional transactions. Since then, the world has moved online and systems integration has improved. Pilot studies using blockchain technology have reached the point that a mainstream conveyancing platform with self-executing contracts linked to all the required elements in a property transaction (including verifications and security checks) could drastically streamline property sales and reduce the involvement of lawyers until later in the process.

Sandbox pioneer Valla is an online platform built by non-lawyer founders. Danae Shell and Kate Ho recognised the need for affordable legal advice and support for people who have been treated unfairly at work or are involved in other employment disputes.

Valla does not give legal advice, but its free self-service guides help people understand their legal rights, and where appropriate, prepare a legal case. The platform enables them to fill in forms, generate and upload the documents required to prepare case bundles for claims, tribunals and disputes, and decide next steps – whether to negotiate a settlement, go to mediation or appoint a solicitor.

This type of self-service platform uses an automated workflow to manage routine processes – conducting property checks, generating tribunal/settlement documents – saving users money because it delays involving lawyers until later in the process, if they are involved at all.

The shift to pre-lawyer legal advice and support is not limited to sandboxes and incubators. Veriwise is an online service that helps tenants resolve housing disrepair issues. Its machine-learning platform checks enquiries against 168 housing regulations and identifies statutory breaches, generally around housing disrepair. It then generates letters for the tenant to send to their landlord asking them to resolve the issue and seeking compensation.

Founder Ajay Jagota explains that although Veriwise handles the entire customer journey end to end, it is not a legal services provider. Like Valla, it is regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority as a claims management company. Veriwise customers access legal services via a partnership arrangement with legal representation provider Clerksroom. Veriwise is a hybrid business, part owned by Vesuvio Labs, the tech company that developed its machine-learning platform. Veriwise was launched in December 2021 and is already dealing with more than 1,000 enquiries.

Atlas of AI

Kate Crawford, whose academic credentials include visiting chair for AI and justice at the École Normale Supérieure in Paris, asserts in her book Atlas of AI that AI is neither artificial (it takes a lot of people to build and populate an AI engine) nor intelligent (because it is missing context). Having seen for herself the physical processes behind machine learning and their environmental impact (collecting and processing data has a greater global environmental impact than air travel), she believes Mark Zuckerberg’s 2014 slogan for Facebook developers ‘Move fast and break things’ should be considered a warning rather than a mantra to live by. Although tech regularly breaks preconceptions and limitations in a positive and creative way, automated data-driven decisions can be societally destructive. As legal tech stakeholders have broadened beyond legal services and their customers to include government institutions, regulators, entrepreneurs and funders, the challenge is to move fast, but not break the important things that underpin the UK’s legal system as a world leader.

Follow the clients… into the metaverse?

The main observation here is that the most transformational legal tech follows the client rather than the law firm or the vendor. Law firms invest in tech tools and resources that their clients expect and require – and may even specify in panel tenders. They also tend to be fast followers rather than first movers, quicker to invest in new startups than adopt new technology, which represents a barrier to entry for scale-ups and new vendors. However, their clients are often more willing to experiment with cutting-edge platforms and applications. And where their clients go, law firms will surely follow. The clients are driving the train.

As mainstream banks and large corporates launch cryptocurrencies and NFTs (non-fungible tokens), law firms will surely follow Stephenson Law, which issued the first NFT for legal services on OpenSea last year.

The last two weeks have seen professional services follow their clients into the metaverse. Last week JPMorgan, the first big lender to enter the metaverse, opened the Onyx lounge (named for the bank’s Ethereum-based services) in Decentraland (a decentralised virtual world built on the Ethereum blockchain – tinyurl.com/ypxmuyy3). This was swiftly followed by the first US ‘Big Law’ firm. Washington DC firm Arent Fox announce its new virtual office in Decentraland having helped PwC Hong Kong become the first professional services company to purchase a virtual site in metaverse games-based platform The Sandbox in December 2021.

As well as bringing the firm closer to their clients, crypto chair James Williams told American Lawyer that the firm’s plans included ‘not only the delivery of legal services, but also training aspects, being able to assemble individuals from different offices, as well as the networking and business development aspects of having a presence in the metaverse’.

Corporate legal got there first, however. During the pandemic, Hewlett Packard Enterprise legal department started organising VR (virtual reality) team meetings.

According to general counsel and corporate secretary Rishi Varma: ‘VR is used by a large number of our legal professionals for the delivery of their day-to-day work. A growing number of team members meet regularly in VR for deals, management, work updates, social events and more. We have launched a VR campus accessible to all our VR-equipped team members, which makes us one of the first, if not the first, legal department in the metaverse.’

How long will it be before companies like Hewlett Packard Enterprise run their legal panel selections in the metaverse and the major law firms jump on a virtual lawtech train to the metaverse?

No comments yet