Cloud technology was already transforming legal services and making courts more efficient before the pandemic hit. 2021 will present new challenges to a remote workforce

Traditionally, this is the time when people make predictions for the year ahead – but in 2021 predictions seem somewhat hollow. Nobody anticipated 2020’s global pandemic, although it has been flagged up as a possibility multiple times in recent decades. In fiction, Nigel Watts’ 1995 novel Twenty Twenty is set in 2020 during a pandemic (Watts died in 1999, so did not witness the accuracy of his dystopian vision). ‘If anything kills over 10 million people in the next few decades, it’s most likely to be a highly infectious virus rather than a war,’ said Bill Gates in his 2015 TED talk, ‘The next outbreak? We’re not ready’, which was inspired by West Africa’s Ebola virus epidemic. However, I cannot find mention of a likely pandemic in predictions for 2020.

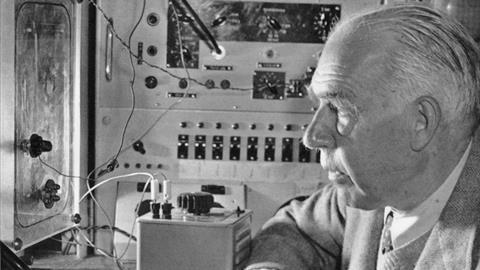

‘It is hard to make predictions, especially about the future,’ is a quote attributed to Yogi Berra, the late baseball coach of the New York Yankees, and famous Danish physicist Niels Bohr (pictured above), among others. This year’s various legal tech predictions include ‘light at the end of the Covid tunnel’, a post-pandemic ‘return to normal’ and a variety of applications for artificial intelligence and automation ranging from predictable to highly imaginative.

Notwithstanding the optimism, it is clear that Covid-19 is lasting long enough to lead to permanent changes to the business of law, which for the first time is entirely dependent on technology. So rather than attempt to make predictions, this article highlights some of the opportunities and threats facing legal tech in 2021.

Opportunities and threats

We are unlikely to see a return to the office any time soon, which is an issue for many firms whose offices represent an important part of their brand. Tech trends for 2021 reflect this, with new products designed to support remote, mobile and hybrid working including new, faster smartphone models – foldable, rollable, scrollable, multi-screen etc – and the rollout of 5G to laptops as well as phones. Better connectivity supports cloud functionality, including streaming services and connected devices, and unsurprisingly, an explosion of health, hygiene and disinfection tech.

Digital transformation and the shift to cloud computing/Software as a Service (SaaS) started before the pandemic. Entrepreneurs and investors saw the potential of applying technology to the conservative, but highly profitable, legal sector. And law firms realised that an ‘innovative’ brand improved their market position in the face of increased competition from alternative legal services providers and the Big Four consultancies.

Meanwhile, public sector and professional institutions saw the opportunities that cloud technology presented to make legal services and the courts more efficient and accessible. The pandemic is accelerating digital transformation and progress towards online courts, uncovering challenges and opportunities along the way.

The pandemic mindset

Despite the many challenges presented by Covid-19, the relationship between law and technology is benefiting from what Azeem Azhar describes in his Exponential View podcast as the ‘urgency, creativity, constructive competition and collaboration of the pandemic mindset’.

Arguments around lawyers’ reluctance to adopt technology constraining law firm innovation have faded in the light of firms’ rapid switch to working and communicating online, via Zoom or asynchronous communication platforms. As Jack Newton, CEO of legal software vendor Clio, told Business Insider, ‘10 years of legal transformation happened in 10 months’.

In another example of pandemic urgency, 2020 saw rapid changes in the legal tech landscape. Almost every week there were two types of announcement: significant funding rounds boosting start-ups and scale-ups, and M&A activity accelerating market consolidation.

These developments fulfilled expectations that the tech adoption necessitated by the pandemic would fuel a boom in legal tech investment – both in terms of funding and purchasing. Globally, contract management and automation companies are attracting the most investment capital, and practice management system vendors have been the most popular targets for acquisition. US lawyer and legal technology journalist Robert Ambrogi, writing for Above the Law, identified the pandemic as a key factor in these deals because it accelerated law firms’ move to cloud-based systems and electronic payments.

While 2020 saw more collaboration, with the establishment of new alliances and multi-vendor platforms, competition in the legal tech ecosystem has not always been constructive. In the US, AI research pioneer ROSS Intelligence was forced to close following a copyright challenge brought by Thomson Reuters, which ROSS is disputing on the grounds that judicial opinions in the US are not copyrightable (tinyurl.com/y7yjk2x7). The positive element of this unfortunate situation was collaboration between ROSS’s former competitors Fastcase, v Lex and Casetext which are giving ROSS customers and access to justice account holders free access to their platforms for the remainder of their contracts. However, this raises the question for legal tech purchasers of what happens when you invest in start-up technology that is discontinued or acquired, and you need to change suppliers or platforms unexpectedly.

Another practical challenge which Covid-19 has exacerbated, and which will continue into 2021, is introducing new processes and technology to an entirely remote workforce, and training and engaging users who have already had to adjust to working online. This is about improving tech competency among lawyers and communicating effectively across an online user community, enabling it to access IT and peer support without overwhelming people with online instructions and Zoom meetings.

Discrimination

Data ethics in relation to AI and automation has been a major discussion topic for several years. Last week, an Italian court decided that Frank, the algorithm used by Deliveroo to assign scores to riders, was discriminatory because it automatically penalised riders for a late cancellation without recognising when this was due to an important reason, like a family emergency. But AI software can also be used to fight discrimination and harassment. Legal tech start-up Valla uses data extraction and analysis to predict likely awards in discrimination cases.

The International Bar Association recently produced a paper on Trust Tech, systems that use emerging tech such as AI and blockchain to facilitate better reporting and awareness of harassment in the workplace – which hit the headlines in respect of several law firms in 2020. This provides a safe space for employees to speak up, either anonymously or confidentially, thereby driving cultural change.

Regulation vs innovation

As government regulators and professional institutions are increasingly involved and investing in legal tech, they have bought themselves the right and responsibility to influence its direction and consider/decide what it can and should be allowed to do. This raises the thorny issue of regulating legal tech, particularly when it is applied to client data. Conversely, there is a risk that over-regulation would inhibit legal tech’s thriving start-up culture. Steven Tover, CEO at Israeli legal research start-up AnyLaw, which provides a free service, expressed ‘concern that the big players would use regulation to limit competition and innovation’. However, he adds that regulation could address matters of client confidentiality, data privacy and privilege between lawyers and their clients.

Matt Hervey, partner and head of artificial intelligence at Gowling WLG, and co-editor of The Law of Artificial Intelligence, believes that any regulation of technology will have an impact on law firms, adding that users of AI software, including law firms, need to understand the practical risks. ‘AI tools tend to be statistical rather than deterministic – they aim to be right for an acceptable proportion of the time but will also make mistakes,’ he explains. ‘Whether that is acceptable depends on context. It may be appropriate for speeding up reviewing documents for disclosure in litigation or as part of due diligence of a large data room for a corporate deal, especially where the task would be impossible without technology. It may be inappropriate where a significant contract needs to be reviewed thoroughly for its implications [for] an unusual scenario.’

In 2019 former Law Society president Christina Blacklaws’ Technology and the Law Policy Commission explored the use of algorithms in the justice system: how explainable should artificial intelligence systems have to be when they are used to support judicial decisions or use court data to predict case outcomes? The latter is particularly relevant since the British and Irish Legal Information Institute allowed Oxford University researchers to conduct AI analysis on England and Wales court judgments (tinyurl.com/y7smus32).

Notwithstanding the growing use of automation in litigation processes and court procedures moving online, the court digitisation project is far from complete and courts remain open for face-to-face hearings during the current lockdown. ‘The tech, at present, does not support decision-making in UK courts as we judges give the judgments still, not the machines,’ explains deputy district judge Karen Rea. ‘We use Zoom and Cloud Video Platform in court so [the issues are] more about data protection and governance.’ Clearly there is still some way to go before AI justice becomes a regulatory issue in England and Wales.

Bohr said ‘every great and deep difficulty bears in itself its own solution . It forces us to change our thinking in order to find it’. Perhaps 2021 will be the year when legal innovation gets real.

No comments yet