The Sex Disqualification (Removal) Act 1919 turns 100 on 23 December. Eduardo Reyes looks back on a century of shifting attitudes, both in the press and the Council chamber

THE LOW DOWN

The countdown to 23 December 2019 – the centenary of the Sex Disqualification (Removal) Act receiving royal assent – has had academics delving into the archives for stories of early women lawyers. This year also marks a century of the Gazette and other legal journals reporting on the ascent of women in the profession, including news on both the male allies who pushed the door open and fears of ‘she-bear’ women litigators. These yellowed magazines also record a chequered history of progress, and at many points both reflect and promote the sexism that persisted – from dubious humour to outright prejudice. That context includes a ‘ladies’ annexe that was opened by comic actor Sid James and the long wait for the Law Society Council’s first woman – which took another 58 years.

The Law Society’s record of opposing the admission of women to the profession in the early 20th century, president Mark Sheldon reflected in 1992, ‘is hardly creditable’. Sheldon supported ‘firm but tempered measures’ to tackle the discrimination women lawyers still faced in their professional lives. No doubt Mrs Sheldon was proudly supportive – the Gazette reflecting her role by printing a specially commissioned photograph of her to accompany its reproduction of the president’s address.

Alongside The Sex Disqualification (Removal) Act 1919, today we mark a century of the Gazette and other legal titles (the Solicitors Journal in particular) covering women’s experience of the law. Former editors no doubt believed they superintended competent papers of record; and a dive into the archived copies shows these journals to be invaluable sources. Yet they are sources that admit and omit coverage of events in ways that tell us much about the world in which women lawyers have made (or failed to make) progress.

The record starts promisingly enough in 1919. The Gazette, Solicitors Journal and the Law Times gave wide coverage to the men whose deliberations opened the legal profession’s doors to women. Even though the record has acquired the patina of age, the sense of momentum is palpable. Lord chancellor Lord Birkenhead (FE Smith), who had once opposed the admission of women, put his skilled oratory to the task of shepherding the necessary legislation through parliament.

Earlier that year, for a 28 March special meeting of the Law Society Council, called to consider its position on the admission of women, the Law Times and Solicitors Journal reported in detail the confident hand that supporters of admission were now playing. Society president Richard Pinsent used his opening remarks to highlight the change of heart expressed by a one-time opponent of equality, Sir Homewood Crawford (absent through illness), in a letter: ‘Speaking for myself and in the light of materially altered circumstances, I say unhesitatingly that, provided the Bar will by statutory enactment be as free to women as it is sought to make our branch, we ought not to place any further obstacle in the way of women attaining the object of their ambition.’

The motion was moved by another former Society president, Samuel Garrett, who had the satisfaction of seeing the argument shift his way. ‘Minorities,’ he is recorded as saying, reflecting on his own long-term support for equality, ‘had a way of becoming majorities in these progressive times.’ Garrett, as the brother of both the pioneering physician and mayor of Aldeburgh, Elizabeth Garrett Anderson, and suffragist campaigner Millicent Garrett Fawcett, was close to women who acted to secure that progress (yet strangely the only legal press report linking him to his sisters was his 1923 obituary).

'Unforeseen difficulties, arising from the nature of the Mess premises, had shown themselves in the way of admitting women to the Mess. It was therefore decided not at present to admit women'

Solicitors Journal, 1923

Women’s contribution to victory in the Great War was invoked by all supporters. London Council member Lieutenant Wood even spoke in uniform: ‘Liet WOOD (London), who wore khaki, said he hoped the resolution would have been passed unanimously…’

Speeches against were also reported, but they were few. ‘Member GB Cook noted that men had made a greater sacrifice, dying in such great numbers in the trenches. “Was it not [the women’s] hearths and homes that men went out to defend?” he said.’ Member JW Reid, it was reported, was exercised by the idea of women in litigation. ‘He did not pretend to have a very great experience in Judges’ Chambers at the present times. It used to be called the “Bear Garden”, and [he] hoped that there might not be found there in a very short time a great many she bears to set up a fight between man and woman in matters of law. It would be a very great misfortune.’

Editors and correspondents certainly had plenty to say about the prospect of women in the law, even before the first solicitor, Carrie Morrison, was admitted in December 1922. In June 1919, the editor of the Solicitors Journal had some advice for women aiming for a career at the bar on what it took to succeed: ‘To unlimited industry and perseverance – we need not labour the ability – must be added unfailing health.’

And what followed such a rich vein of coverage, advice and debate? The answer is a huge decline in editorial interest. What is covered in the years that follow reflected both a pattern of inclusion and exclusion. The discourse on equality, as played out in the legal press, switches to the battles that raged over toilets, and membership of the law’s clubs and societies.

On 30 January 1923 the Bar Mess, the Solicitors Journal reported, ‘held a general meeting to consider the application of a woman for membership. There was no wish to exclude the lady in question, who is personally the most popular with her male colleagues of the new lady barristers; but unforeseen difficulties, arising from the nature of the Mess premises, had shown themselves in the way of admitting women to the Mess. It was therefore decided not at present to admit women’.

Did they mean the toilets? If so, early women lawyers were already on the verge of greater success over at the Law Society. Earlier that year, at a special general meeting of Council on 26 January, London member Mr Percy Chambers asked ‘whether [the Council] proposed to provide [women solicitors] with suitable separate cloak-room and lavatory accommodation?’ A special committee of the Council, the president replied, had been meeting for weeks and the works would be carried out. By 1924 it was finished.

LADIES’ ANNEXE AT THE LAW SOCIETY’S HALL

By A Special Correspondent

‘Who would have believed that The Law Society, when at last it opened its doors to “the Sex” would be so Miltonic in its choice of décor to set off the charms of wives and sweethearts of its members? For indeed the predominant colour of the elegant flock wallpaper, the chaste covers of the banquette seats, and even the walls of the lavatories… is described by the designer, Mr Michael Inchbold, as ‘Amaryllis, or pale flame.’ … an enchanting little corner in the rather grubby deserts of WC2.

‘When the Press were allowed a preview of the new annexe on 25 April, against the background of the reassuring sound of champagne bubbling into glasses, uninhibited expressions of admiration could be heard from the most blasé journalists.

‘In the cocktail lounge, decorated in the favoured simple-baroque style (that is, elaborate and expensive materials used with almost stark simplicity but relieved by restrained and even more expensive ornament), elegant padded leather, real marble in white and black, and unashamed imitation marble wall-paper in blue, contrive to give cool luxury very well suited to the ingestion of exactly the right number of dry Martinis.

‘The dining-room itself, glorious in colour, cannot fail to stimulate a nagging thought: can the food possibly live up to the décor? … the guests are going to love it: unattached solicitors should be in great demand as escorts, and there may well be a fashionable trek from Mayfair and Chelsea to Chancery Lane – but only for lunch: alas, dinners will not be served, or at least not at present.’

Solicitors Journal, 5 May 1961

Toilets were one thing, but what the legal press did not pay attention to was the progress of early women lawyers. Skipping forward to 1928, the year of the Equal Franchise Act, or 1933, the year retailer John Lewis appointed a woman as its in-house lawyer and the first female-only partnership was formed, neither the act (nor these legal firsts) merited coverage. Instead, mention of women and the law in 1928 was limited to topics such as the delicacy (or otherwise) of women jurors. ‘Opinions differ,’ the Solicitors Journal ruminated, ‘as to the propriety of women being members of a jury which has to try a charge of indecency where the parties concerned are males only.’

Women lawyers merited no mention in the Law Society Council’s report for 1928. This prompted member Edward A Bell, an original supporter of the admission of women lawyers, to note there were ‘some omissions’ in the address: ‘Amongst others, there was no reference to their forensic sisters, who had now become an established entity.’

In 1933, among mentions of women in the legal press are passing allusions to women speaking in law’s debating societies. In March, Miss MC Davies opposed a motion at the Hardwicke Society: ‘That State Education has overstepped the limits of usefulness.’ But a far bigger concern for the 1930s was the way lawyers and the legal system were responding to the increase in divorce and separation – including worries over the use of staged evidence of infidelity at hotels to provide ‘grounds’ for the end of an unhappy marriage. Other questions of sex-based morality were also considered, including the problem of ‘The Debtor with an Opulent Wife’.

In the decades following 1919, the number of women lawyers slowly increased. They are there in the long, closely typeset lists of Law Society finals results and admission lists. But this is rarely remarked on editorially. Whereas the Great War had a major role in steering the profession’s view on women in law, the second world war, going by the legal press, did not.

In 1948 prime minister Clement Attlee’s reforming Labour government was poised to introduce legal aid. The Gazette did record an event involving an aspiring woman lawyer, though it took a detail of her marriage to achieve such coverage. The October report runs: ‘In the Honours Examinations held in June 1948, Miss Dorothy Clare Waine was the only candidate placed in the First Class, and was awarded the Clement’s Inn Prize.’ The report noted that she had since married another prize winner, the only First in March’s exams, Mr JH Craik: ‘Thus establishing a family record which we have little hesitation in saying that none of our readers is likely to be able to beat… a unique distinction.’

When the Law Society Council voted to alter its rules to admit women in 1919, the vote had been convincing at 50 in favour and 33 against. But not all rules related to the Law Society’s Hall (as its Chancery Lane headquarters was then called) had changed. A growing number of women solicitors and female guests were running up against arcane etiquette relating to Chancery Lane’s dining and social facilities. A woman solicitor could bring her non-lawyer husband to lunch, but not a non-lawyer woman guest; and a male lawyer could bring neither a non-lawyer wife nor a woman guest.

Just before the 1960s started to swing, the solution reached by the Council – which would not welcome its first woman member until 1977 – was not a rule change, but the creation of the Ladies’ Annexe. In contrast to the grudging provision of toilets in the 1920s, the Ladies’ Annexe aimed at making a real impact (see box, above).

The Gazette’s editor made the annexe the lead item in April 1961: ‘It is expected that for a time there may be a rush of ladies to see inside the walls of the once Forbidden City,’ the editorial gushed, ‘and I have been asked to say that tables must be booked for lunch in the ladies’ dining room. In addition to a dining room, the new accommodation includes a bar, lounge, powder room and cloak-room.’

Starters included prawn cocktail and foie gras; mains, sole fillet and ‘Boef Stroganoff’. Solicitors could bring up to three guests, though for male solicitors that had to include at least one woman. Who did the Society invite to officially open such a special project? Peculiarly enough, the comic actor Sid James.

The Ladies’ Annexe closed in 1976, already anachronistic in the year after the Sex Discrimination Act was passed and the Equal Pay Act enacted. ‘The bar’s a special case,’ complained one male correspondent, ‘it’s forbidden to women guests at lunchtime, though not in the evenings. The reasoning behind this baffles me completely. Could it be that women at lunchtime are too much of a distraction, disturbing serious male discussion of intricate legal problems – while in the evenings, with the cares of the day put aside, male solicitors are pleased to have their attention distracted? … And another thing – how are we supposed to get our lady guests from one permitted room to another? Must we carry them around the insanely forbidden areas?’

‘Breakthrough for women’, was the 25 September 1975 Gazette headline that announced the overdue change: ‘All rooms in the Law Society are now available to members to entertain their lady guests.’

Reflecting a world that was changing fast, some solicitors used the letters page of the Gazette to challenge attitudes and assumptions. On rape, columnists challenged readers, just as readers took on columnists. Anonymous columnist ‘Furnival’ prompted this observation from solicitor AE Allen in Dunbartonshire. ‘In his article, Furnival cites “most clubs, boardrooms, saloon bars and other masculine places” as venues for ardent, if ill-founded discussions on rape. Were Furnival to visit the wardroom of HMS Neptune, he would find us discussing far more interesting, amusing and elevating topics than the finer points of the rapist’s art.’

The 1919 Club (the Association of Women Solicitors) was campaigning for tax relief on the portion of a working woman’s earnings that were used to pay for childcare, mocked in the letters page by DG Lindsay (Whitchurch-on-Thames) who demanded tax relief for working men with stay-at-home wives.

With Margaret Thatcher elected to lead the Conservative party, Furnival considered that women in the law would advance further if women-only chambers and law firms were created, to make career breaks to have children easier: ‘Both could operate on the basis that a certain proportion of the principals’ time, taken as a whole, would be spent in pregnancy, childbirth and suckling.’ But, Furnival concluded, the proposal ‘rubs against too many clichés of modern thought. Feminists, like all agitators, want it all ways’.

In reply, Ms Joyce Arram, of London N2, said: ‘I would not wish to work in such a restrictive atmosphere.’ She added the arrangement might suit ‘Furnival’, as he ‘wouldn’t be shown up by the superior brains of… female colleagues’. Another, Eileen Meredith of London, W11, saw just one advantage – being free of the ‘daily aggravation of pontifications from pompous male bores like Furnival with which our profession is sadly riddled’.

By 1982, the politician and one-time chemist and barrister described by Furnival in 1975 as a ‘middle-aged mum’ was prime minister. This was also the year the Sex Discrimination Act 1975 was successfully used by solicitor Tess Gill and journalist Anna Coote to challenge Fleet Street wine bar El Vino’s ban on women drinking in the bar with male colleagues and contacts.

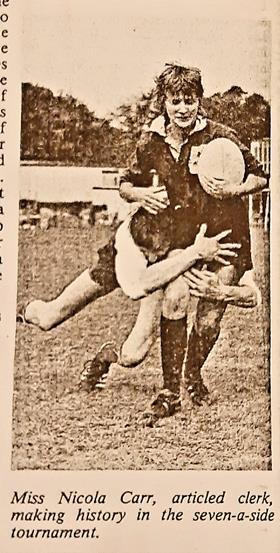

The case was national news, but did not get a mention in the Gazette or Solicitors Journal. A more temporary women’s breakthrough (see box, below) did – the female articled clerk who exploited a loophole to play in an all-men rugby tournament.

The Law Society Council was also noting the contribution of Miss CE Evans, its first woman Council member, who decided to stand down after five years. ‘The Council has learned with great regret,’ the Gazette reported in July 1982, ‘that Eileen Evans has decided not to seek re-election… she brought good common sense, and to those of the Professional and Public Relations committee, a feminine viewpoint which was particularly useful in the work of the subcommittee on Sexual and Racial Discrimination.’

That same year, a letter from ‘Fiona’ noting her difficulty in getting articles and alleging sexism, prompted a reply headed: ‘Explaining to Fiona.’ With so many women seeking to enter the profession, the correspondent ‘BCR’ noted, he could fill articles at his firm with well-qualified women alone: ‘All the same, I feel that I have to make an effort to limit the number of women whom we take.’

SEXES AND SEVENS

‘The annual Law Society Rugby Football Club seven-a-side tournament was held this year on Sunday 3 October.

‘A large crowd watched a very enjoyable day’s rugby with 20 sides competing in the main competition and the plate competition for those knocked out in the first round of the main competition.

‘Allen & Overy, winners for the past two years, were unexpectedly but comprehensively beaten by Slaughter & May [sic]…

‘This year history was made when for the first time. Miss Nicola Carr, an articled clerk with William Merrick & Co, played in the tournament generating press and television coverage of the event. Although her presence was greatly enjoyed by all, the rules of the competition have, reluctantly, been reviewed to prevent a repeat performance next year.’

Gazette, 20 October 1982

A decade on and Barbara Mills, the first woman to head the Serious Fraud Office, was the first woman to become director of public prosecutions. Women suddenly became far more prominent in the pages of the legal press. Campaigning lawyerLouise Christian, for example, made headlines for questioning a judgment establishing police immunity for negligence. Also covered were the appointments of women as heads of department – partner Denise Kingsmill’s arrival at Clyde & Co to set up its employment department was one (‘A very exciting opportunity,’ she told the Gazette).

But it is not until 2002 that the Law Society welcomes its first woman president, Carolyn Kirby. By then Harriet Harman was solicitor general and Baroness Scotland (later attorney general) a minister in the lord chancellor’s department. It is Harman’s sister Sarah, a solicitor who specialised in child care and domestic violence, who catches the attention of The Times (quoted in the Gazette), which described her as ‘a redhead, and, like her sister, a beauty… striking… elegant… [with] green, wide-apart eyes’.

Women who have babies go ‘jelly headed’ and struggle to return to their previous standard of work

Consultant quoted in the Gazette, 2002

Less frivolously, the Gazette of 28 February led with the headline ‘Dissatisfied women solicitors to quit PI’, and in the story identified a gender pay gap in the field. Also given prominence that year was a discrimination case: ‘Solicitor wins “jelly-headed” pregnancy demotion case’. The Gazette reported: ‘Nicola Bilsborough, a personal injury litigation assistant… left the firm for six months’ maternity leave, during which [time] she saw her job advertised in the Gazette.’ She was told by a consultant at her firm ‘that women who have babies go “jelly headed” and struggle to return to their previous standard of work’.

Harriet Harman went on to author the Equality Act 2010.

MANAGING PARTNERS

‘Lawyers’ long, antisocial hours are a problem when it comes to meeting people,’ says Alan Jenkins, owner of London dating agency, the Executive Club of St James. ‘For high-earning and high-achieving female partners, the problem is almost worse – they need someone whom they can respect, and who is their equal in terms of salary and career achievements.’

The Gazette, 14 February 2002

So, in 2019, with 51% of solicitors now women, how far have we come?

Perhaps most notably, two years ago the legal and broadsheet press were prominent in publicising the arrival in the legal profession of the ‘#MeToo’ movement, with revelations involving incidents about international firms widely reported.

The Gazette itself also played a role in pressuring large law firms to include partner data in published gender pay gap statistics – several had tried to dodge this, before giving way. The Gazette’s ‘Women in the Law’ page, launched earlier this year to mark the centenary of the 1919 Act, has been used to commission history and comment articles on the early women lawyers and current issues relating to equality in the profession. Topics like ‘feminist judgments’ are explored, and there are many more prominent women lawyers in positions of leadership. That inevitably helps to balance coverage of men and women lawyers.

If that feels like progress, it is also worth reflecting that it is an editorial direction that some readers clearly resent. On any story related to women in the law, diversity and equality, there are online comments, and very occasionally letters to the editor, which reflect views held (and indeed explained to) ‘Fiona’ in 1982 and before.

We can though, reflect on a century in which a Fiona – Fiona Woolf – has been both president of the Law Society and lord major of London. And earlier this year another woman president, Christina Blacklaws, heard the lord chancellor talk of the £150bn boost to the economy gender equality would bring, at a symposium on women’s leadership in law that she had organised. It may not always feel that way for women lawyers, but 100 years is a long time after all.

No comments yet