Perhaps the most powerful scene in the 1955 film The Dam Busters - it will surely be screened somewhere on this, the raid's 80th anniversary - is the one where nothing happens. It's early morning in an empty bedroom. A clock ticks as the camera zooms in on a trophy on the wall: an oar blade from the 1938 Oxford-Cambridge Boat Race, bearing the name H.M.Young.

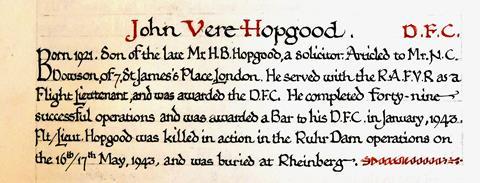

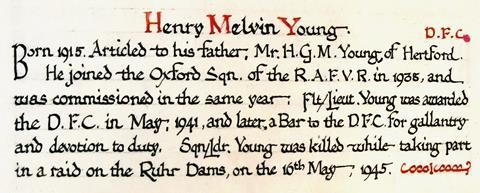

Henry Melvyn 'Dinghy' Young also is listed in the Law Society's Book of Remembrance, on display in the reading room in 113 Chancery Lane. He was one of two articled clerks who commanded bombers in the dams raid: the other was John Vere 'Hoppy' Hopgood.

It is not especially surprising that two of the 19 bomber pilots who made history on the night of 16 May 1943 were lawyers: in peacetime, the RAF Volunteer Reserve recruited disproportionately among the sons of well-to-do families, who would expect to follow their fathers into the profession, as did Hopgood and Young.

But the two were among the most remarkable members of the remarkable band who made up 617 Squadron. I've written before about Hopgood and his outstanding record. In February 1943 the Gazette's Honours and Awards column noted that he had been awarded a bar to his Distinguished Flying Cross for a 'particularly daring' daylight attack on an armaments factory in occupied France, bombing an electrical transformer station from a height of only 500 feet. 'In all his work with the squadron he has displayed the greatest keenness and devotion to duty,' it recorded.

But in April 1943 Hopgood's sister recalled of his last leave: 'He looked pale and very drawn and was smoking heavily, his fingers yellow with nicotine stains. He spoke little of what he was doing (sworn to secrecy) and seemed to find comfort in playing Chopin and Mozart etc on the piano, which he did beautifully.'

Young had a similarly eventful career. He was born on 20 May 1915 in Belgravia, London; his father was a successful solicitor, his mother a Californian heiress. He followed his father to Trinity College, Oxford, where he read law and rowed for his university. He also learned to fly in the University Air Squadron and, while articled to his father, was commissioned into the RAFVR. In 1938 Young wrote to a friend: 'Since we are to have a war, I am more than ever glad I am in the air force. It is a happy, healthy life while it lasts.'

He began the war flying twin-engined Whitley bombers and in October 1940 an engine failure forced him to ditch in the Atlantic. He and his crew were retrieved by a destroyer after 22 hours in a gale-tossed rubber dinghy. Just a month later he came down in the sea again, spending 10 hours adrift off Start Point before being rescued. Hence his nickname.

With two tours of duty completed, Young joined 617 Squadron as a flight commander. At 27, and married, he was something of a father figure to the rest of the squadron, stepping in to manage the training programme: he even had his own typewriter. But he was one of the lads, too. Off duty, he was remembered for sitting cross-legged on the floor of the officers' mess, holding a beer tankard by the jug rather than the handle, taking the occasional pinch of snuff. On the night of 16 May 1943 it was Young who made the cheeky request to his commanding officer Guy Gibson (24): 'Can I have your egg if you don't come back?'

'I told him to do something very difficult to himself,' Gibson later wrote.

Hopgood meanwhile told his Australian squadron mate Dave Shannon: 'I think this is going to be a tough one and I don't think I'm coming back, Dave.' His premonition was accurate. Hopgood's aircraft M-Mother, already damaged by ground fire, was the second to attack the Möhne dam; its bomb dropped late, destroying a power station at the foot of the wall. Hopgood's last words to his crew as he battled to gain height in his blazing aircraft: 'For Christ's sake, get out of here.' Three of the seven jumped; two survived.

Just minutes after witnessing his crash, and one more unsuccessful attack, it was Young's turn in A-Apple. His bomb bounced three times and landed dead on target. 'I think I've done it,' Young called. In fact it took one more bomb, but the dam was already starting to crumble. The code word, the now-notorious name of Gibson's black dog, was radioed to Bomber Command.

Young then accompanied Gibson to the second dam, the Eder, to distract any ground fire while it, too, was breached. Alas Young's run of luck was about to end. On the return trip, A-Apple was hit by flak over Castricum aan Zee, Holland, and crashed in the sea. No dinghy, this time, and no survivors. It was the last of the night's eight losses - a casualty rate of 42%.

The bodies were washed ashore. Dinghy Young is buried with his crewmates in Bergen General Cemetery.

Eighty years on, and nearly 70 years since the iconic film, the dams raid has been subject to two revisionist interpretations. The first, labelling it as a war crime - nowadays the raid would fall under the prohibition on attacking 'works and installations containing dangerous forces' - does not merit much discussion. This was 1943. If there was any doubt about the nature of the conflict with Nazi Germany, it had been resolved by Joseph Goebbels' 'Totaler Krieg' speech that February.

The second revisionist interpretation, that the raid was of negligible military importance and that 130 lives were thrown away on a publicity stunt is a little more persuasive. The human casualties on the ground were mainly women and children, the largest group of them 753 Polish and Ukrainian slave workers killed in their barrack block. Most of the physical damage was repaired within weeks or months. The 'bouncing bomb' was never used again.

But we saloon bar pundits should tread warily here. The dam busters got away with only (sic) 42% casualties because the Luftwaffe was caught by surprise - presumably its commanders thought the RAF would not be mad enough to make a raid on a full moonlit night. They wouldn't be caught napping twice.

And even if the raid was just a piece of what Churchill called military theatre, it had an immediate and profound impact. We know now that the tide of the war was already turning in spring 1943, but there was little sign of it in that dreadful year. The dramatic photograph of the breached Möhne dam blazed on front pages, including that of the New York Times, the message 'We are winning'.

The message hit home in Germany, too. At the direction of a shocked Hitler, 70,000 workers were deployed to repair the damage and thus no longer available to build tank factories or fortify the Channel coast. The realisation that every piece of infrastructure in the Reich now needed protection from pinpoint attack caused the diversion of thousands of guns and other resources from the Eastern Front, where the decisive battle of Kursk was about to rage.

No one can say by how much the dams raid shortened the war, but 80 years on we can agree that it did. Some consolation, perhaps, for the cruelly shortened lives of two very fine articled clerks.

6 Readers' comments