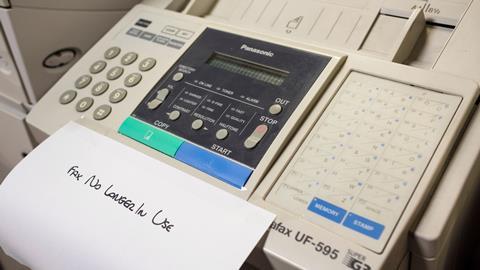

The last use of the facsimile machine in the old Gazette office before the February 2020 fire was to receive a blood-curdling warning from a prominent defamation firm. Along with parts of the NHS, libel lawyers seem to have been the last users of this hangover from pre-internet information technology. The only other messages we received were from companies offering cut-price fax machine paper, which must set a new standard for chutzpah.

Now, telecoms regulator Ofcom is consulting on proposed changes to the rules that will mean telecoms operators will no longer be required to provide fax services under their universal service obligation. It will publish a statement early next year.

Fax has been around for a surprisingly long time. An 1843 patent filed by Scottish inventor Alexander Bain, who also came up with the first electric clock, describes a method of remote printing by synchronising a scanner and a printer. The first practical fax machine, the Pantelgraph, which sent images over telegraph lines, dates from the 1860s.

The first modern commercial machine was marketed by Xerox in 1964, in the era when computers meant mainframes housed in their own rooms, if not buildings. I first encountered faxes in the 1980s: the weekly science magazine on which I worked had a dedicated line from London to the printers near Luton. Sending a fax meant making a preliminary phone call to make sure someone was standing by at the other end, then waiting for the machine to warm up and guiding the heat-sensitive paper by hand as it emerged from the rotating drum.

Apart from sending late copy to the typesetters, our magazine's fax machine had two uses. It was the high-tech highlight of the office tour given to visiting VIPs before we steered them to the pub. It was also a way to wind up unwelcome newcomers, like management trainees. 'They're running out of paper up at the printers,' we would tell them. 'Could you fax them up a dozen blank sheets of A4?'

Even then, the clock was ticking for our machine, and indeed for the entire British fax industry. Ours was manufactured by Muirhead in southeast London: I know because the company once employed me as a forklift truck driver, though that wasn't why it went out of business. The actual reason was a technical standard known as ITU G3, which dates from 1980. This overcame a fundamental problem with first and second generation machines, that they could communicate only with those from the same maker.

The creation of an international standard meant that any machine could communicate with any other via the public telephone line. Like much innovation in the 1980s, it was driven by Japan, where the complexities of the alphabet (two 46-character phonetic alphabets and a couple of thousand Chinese characters) defeated text-based telecommunications. By the mid 1980s, everyone in Japan had a Japanese-made fax machine: as a correspondent in Tokyo I envied my colleagues who would hand-write their copy and fax it in to the office from portable devices hooked up to public phones.

By the early 1990s developments in computer software had solved the Japanese typewriting problem (you type phonetically and the system throws up elegant character options to select). But the fax stayed around in computer-phobic sectors such as healthcare, where, bizarrely, for many years it was regarded as more secure than email.

The last holdout is the perceived need for wet signatures to validate certain transactions, thus ensuring fax's survival in the law. Now, more than two decades after the government had its first stab at asserting the validity of electronic signatures through the Electronic Commerce Act, the final legal doubts are being removed.

Even for those who still cling to wet signatures, high resolution phone cameras have rendered obsolete the need for a stand-alone image-transmission device. The fax machine will not be missed, except perhaps by libel bullies and connoisseurs of hoary courtroom anecdotes.

'He said ”fax it up”, My Lord.'

'Yes it does, rather.'

11 Readers' comments