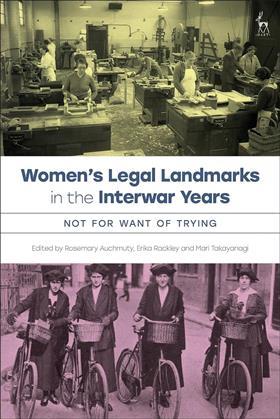

Women’s Legal Landmarks in the Interwar Years: not for want of trying

Edited by Rosemary Auchmuty, Erika Rackley and Mari Takayanagi

£76.50, Hart Publishing

★★★★★

Changes to society’s attitudes toward women and girls, and the laws which affect them, can seem so obvious with the benefit of hindsight that it is hard to imagine those changes were difficult to achieve at the time. This eminently readable book summarises a collection of campaigns for equality between the wars and carries potted biographies of the women who made change possible.

I loved reading about Elsy Borders – the Erin Brockovich of her day – who played an important role in turning building societies into the friendly mutuals we recognise now. It would be amazing, but exhausting, to travel back in time to catch up with the indefatigable Constance Markievicz, an Irish politician and activist who gave away her fortune and refused to take her seat at the Westminster parliament on principle.

Often progress is not linear, or includes milestones which are forgotten in retrospect. A woman who gets married should be offered congratulations rather than a P45, yet it took decades to end the marriage bar to prevent married teachers from working in schools. The dreary-sounding Ministry of Health memorandum 153/MCW, enabling birth control advice to married women, was life-changing in its effect. Still more fundamental was the official recognition that having children should be a choice – this remains an issue in the context of restrictions on access to abortion.

The book does not shy away from explaining that different groups of women had different priorities, particularly once the totemic result of equal voting rights had been achieved. Should the focus be on equal rights, such as the right to be a solicitor, or on winning recognition that women’s different roles were nonetheless equally valuable to men’s roles? Debates started by the Six Point Group in 1921 can be traced through to the Sex Discrimination Act 1975, while cases on equal pay for work of equal value continue to come to the courts today.

Reflecting on my own legal contribution to society, I assume people will be thankful for the provision of public toilets at Aldershot bus station, whether or not they think about my carefully drafted lease. And because women’s rights do always seem to be affected by toilets, there is a chapter on the provision of lavatories at the Law Society in Chancery Lane, including the male allies who championed them.

One final example – of the Industrial Courts Act 1919, which allowed women to act in a judicial role before they were able to practise law or sit as jurors. The illogicality of this helps demonstrate how every single step to equality had to be won. None of the rights we enjoy today was inevitable. There was always a women’s movement in the 20th century. If change took some time, it was not for want of trying.

Suzanne Gill is a partner at Wedlake Bell

No comments yet