Silent film history that speaks volumes

Gold, Violet, Black, Crimson, White

David Hewitt

£11.99, Matador

★★★✩✩

This is a fascinating history of silent cinema in its early days and the novel legal complications with which it was confronted. The book mainly describes films that came out during the first world war. I knew that silent films had text cards with dialogue and plot explanations but some cinemas had actors who voiced the script.

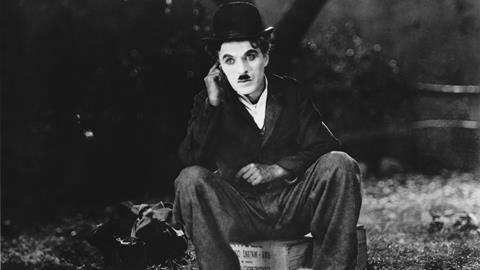

This was the era of Charlie Chaplin (pictured). But the book is largely about a silent film called Five Nights, which was a 1915 British romance directed by Bert Haldane and starring Eve Balfour and Thomas H. MacDonald.

Five Nights became notorious because it was considered offensive and banned. As lawyer David Hewitt explains, this led to court cases and debate about who was offended and why.

It was certainly popular. The film is about a rich young artist with too much time on his hands. He woos a Chinese woman in Alaska, falls in love with his own cousin, gets the cousin to disrobe in front of him, and shoots a Chinese man dead. Plenty of scope for offence there.

The protagonist was offended by the inference of immorality. She said, ‘if the film had been like the book, I should not have been surprised, but it is much milder’.

The film opened in Preston before it was seen anywhere else. On 30 August 1915, Five Nights was shown at the old King’s Palace theatre. In the audience that stiflingly hot Monday afternoon was the town’s new chief constable, James Watson. He was appalled by what he saw. The film was ‘offensive and objectionable’, he said. The distributors read the comment and issued a writ against him, claiming damages of £5,000 – a considerable sum.

Film censorship began. Early cinema exhibitions were subject to the Disorderly Houses Act 1751. The Cinematograph Act 1909 was primarily concerned with introducing annual licensing of premises where films were shown, particularly because of the fire risk of nitrate film. The act began to be used by local authorities to control what was shown. The film industry responded by establishing a British Board of Film Censors (BBFC) in 1912. A precedent was set.

David Pickup is a partner at Pickup & Scott Solicitors, Aylesbury

No comments yet