Descent into Darkness: An Explanatory Guide to Shakespeare’s Macbeth

Nicholas Dobson

£28.99, APS Books

★★★★✩

The commonwealth of the canon that constitutes English literature has always been a source of inspiration for common lawyers and for those writers purloining the stories of law for narratives to expound and explain the human condition.

The canon – of which Shakespeare is a Herculaneum pillar – is now systematically deconstructed from without. But for students, scholars, and practitioners of law, the recognition of a symbiosis between law and literature and law as literature is an important development in understanding language (written and spoken) and narratives (stories with meanings), and the core social construct (law as a form of order to living and the pre-contracted human condition).

It is therefore welcome when practitioners of law – the plumbers – engage in analysis of and reflection upon narratives from the canon. Such contributions may shed light upon a text seeped in bloodshed, crime, immorality, corruption and loss seemingly outwith the law.

Nicholas Dobson enters this violent world as both legal practitioner and a scholar of English literature to illuminate our Shakespeare – oft now considered boring, irrelevant and inaccessible. It is a world where ‘legal interpretation takes place in a field of pain and death’, as Robert Cover put it (Violence and the Word 95 Yale L.J. 1601 1985-1986). Dobson provides us with original text and interpretative analysis of this tragedy.

While ‘formal’ law as a normative order is absent in Macbeth, there is the septic, normative decay and transgression as the fatally flawed protagonist embarks on his ‘sombre sojourn into hell’ following the triumph of his ego, manifest through reliance on false prophecy (a misrepresentation, indeed).

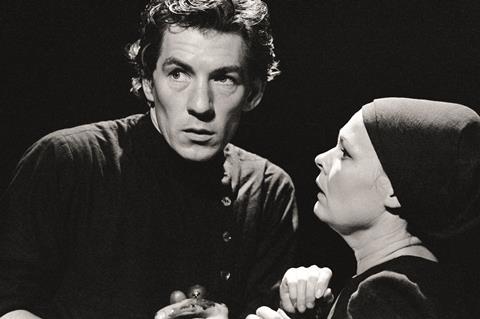

Macbeth’s fall, political and moral, aided and abetted by Lady Macbeth, occurs amid claustrophobic domestic misery (exemplified in the 1976 RSC production at the Other Place in Stratford), and is, as Dobson makes clear, as much about his awareness-consciousness of his actions in terms of kingship/public and kinship/private.

Macbeth’s drive overwhelms him when his subconscious phantasms are unleashed after the spectral encounter upon the blasted heath with the feminine – Lady Macbeth and her sisters. But these are his actions and his consequences, for which he bears sovereign responsibility and which set him on ‘the primrose way to the everlasting bonfire’.

Dobson is clear that our protagonist Macbeth exemplifies the implosion of Jerusalem and Athens. Tragic hubris brings fall as perdition, the consequences of the excess of transgression that creates the void of chaos which humankind cannot bear and which must therefore be righted after wrongful undoing.

Enter law and order stage-right to restore normative dominance and sovereign certainty after the descent into darkness and chaos (the inversion of Macbeth’s ‘returning as were as tedious as go o’er …’).

But are the transgressive act and the expression of the phantasm both necessary for the appearance of ‘law and order’ in all forms of human existence to be maintained? Our drive toward a descent into the temptation into darkness may be the human condition which demands the penalty of the law.

Christopher Stanley is the litigation consultant at KRW LAW, Belfast

No comments yet