For some readers of the Law Society’s new guidance on the impact of climate change on solicitors, this may be their first exposure to the phrase ‘advised emissions’ – although they may have come across other names for the same broad concept, such as Scope 4, Scope X, lawyered emissions, or even our brainprint. The underlying premise is that while businesses are being asked to measure and reduce greenhouse gas emissions – most commonly by using the science-based targets which categorise such emissions as Scopes 1, 2 or 3 – these do not capture all the emissions which flow from a business’s activities. So it is, for example, that fossil fuel companies do not count emissions from the fuel they sell us when we burn it, and airports ignore the emissions generated by the planes that take off from their runways.

In the case of law firms, the emissions we record as our Scopes 1-3 are relatively modest. The emissions we generate in the act of providing our services are marginal compared with many industries. And when we are asked, as part of a client’s supply chain, what emissions were involved in providing them with advice, this too (if we are not flying teams of lawyers around the world and spending lavishly on corporate entertainment) is not a big number.

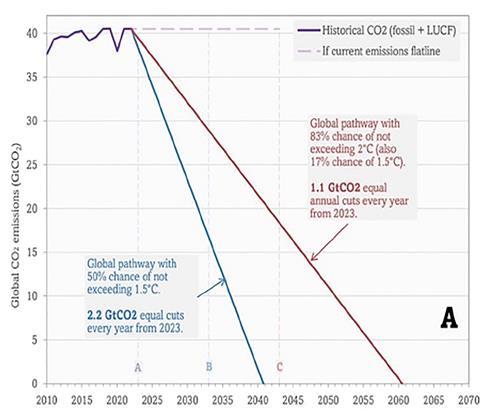

The graph above illustrates the scale and speed of change required to achieve the Paris Agreement aspiration of keeping increases in global temperatures to no more than 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels.

If a law firm or its staff are interested in exploring the optimal contribution they can make towards this, and/or if its clients want to know whether their advisers are taking this challenge seriously, the best way to do this may be through engaging with their advised emissions. This means looking at the emissions associated with the advice they give and taking steps to ensure this is reducing over time in line with the reductions the IPCC has indicated are necessary to meet that Paris Agreement ambition.

The theory underpinning this is that lawyers’ own emissions are small, but any project generating significant levels of emissions will have many lawyers engaged, as it is likely to involve large sums of money and significant risks requiring management and mitigation. How can we calibrate our engagement so that it is on matters which are consistent with the necessary emissions reduction trajectory?

Many clients are challenging advisers to demonstrate they can help them in their transition to low or no emissions and that they are committed to this, not just in the advice they provide, but in not providing advice which contributes to harmful practices by others. Increasingly, lawyers are focusing attention on clients who are evidently committed to transitioning and are most likely to be prominent in the emerging clean tech and equivalent markets of the future. There is a feeling of a direction of travel becoming established and a virtuous circle gaining momentum.

This is where the advised emissions concept comes in. It is not a process for putting hard numbers against particular advice. In terms of attribution, this would be so complicated one can imagine arguments over the best way to calculate it continuing until and beyond the remaining carbon budget had been exhausted. Rather, it is (in this, its still nascent stage): first, a recognition that this is a legitimate and relevant issue to be engaging with; second, a process of internal assessment of the industry sectors a firm serves, the levels of emissions the sectors generate and the potential for these to decrease in the short term; third, consideration of the clients the firm currently works with and/or might in the future and their appetite for transition; fourth, analysing the matters the firm is invited to advise on, taking into account the extent to which these are consistent with such a transition, taken as a whole; fifth, all of this informing the decisions it takes in terms of the deployment and focus of its resources; and finally, measuring and reporting on this to understand and improve the firm’s contribution to transition through its work being focused on matters delivering lower emissions year on year.

This is an area where the scale of change required and the complexity of the issue are such that there is likely to be greater progress – and greater impact – by firms sharing learning and adopting similar approaches. Albeit, of course, in a manner consistent with competition law and any relevant professional regulations and duties. This is something which I understand is already being explored by the firms involved in the Legal Charter 1.5.

The reference to advised emissions is the most obvious example of the Society guidance flagging a development which is on relatively few radars at the time of publication but is likely to become more commonplace before the next iteration is published. It is, for example, the case that increasing numbers of clients are asking law firms to explain what their policies are in relation to taking on clients or matters associated with high-emitting activities.

The guidance is clear that there is no requirement for lawyers to engage actively with the concept of advised emissions. It does demonstrate, though, the guidance flagging a live issue for the profession so that those who wish to can look into it further. In doing more than merely addressing compliance, it is not advocating altruism, but recognising there may be enlightened self-interest in proactively considering the potential relevance of advised emissions sooner rather than later.

David Hunter is a member of the Law Society’s Climate Change Working Group and also sits on the UK Regional Board of the Global Alliance of Impact Lawyers. He is senior counsel at Bates Wells

3 Readers' comments