In a week where the Post Office Inquiry focuses on litigation strategy, KCs Anthony de Garr Robinson and Lord Grabiner are first up to explain their role

4.20pm: Grabiner getting a little tetchy with Beer, telling him that he should read out documents in full rather than pick out selected passages. The inquiry sees an email from Neuberger to Grabiner reflecting on their defeat in the recusal application. Neuberger says this is aggravating for a number of reasons but does note that the Post Office refusing to follow their advice about running two appeals together 'gives us an out in terms of our advice appearing wrong'. Grabiner says this was not something that even crossed his mind and that he never considered needing an 'out'.

Beer says he is finished asking questions. Grabiner replies: 'I am tempted to say thank you.'

The inquiry returns tomorrow with WBD partner Tom Beezer and then on Thursday and Friday with Beezer's colleague Andrew Parsons.

4.10pm: Beer says the inquiry has seen correspondence involving the Post Office team suggesting there was an ‘inappropriate relationship’ between Fraser and Court of Appeal judge Lord Justice Coulson. In one internal email, WBD partner Andrew Parsons considered whether Fraser knew Coulson and had spoken to him in advance before the handing down of the recusal judgment to say that an appeal would be coming. Parsons said in the email he would ask Grabiner about this.

Post Office trial counsel David Cavender KC said in another email to Parsons: ‘It looks very much like this is what Fraser J set up in advance – with his mate the former head of the TCC [technology and construction court, then headed by Fraser] – unless you believe in coincidences.’

Grabiner emailed colleagues to say he had discussed the issue with Neuberger and they shared these concerns.

‘It looks as if Fraser J has been speaking either to the listing office or even to Coulson LJ,’ Grabiner said. ‘Otherwise it would be a remarkable coincidence that of all the LJs presented with the papers they ended up by chance in front of the former TCC judge although this is not a TCC case.’

3.55pm: We return, with Beer starting on the day that Fraser refused the application for refusal. An application to appeal would later be dismissed by Lord Justice Coulson. Grabiner emailed Neuberger to say that on first glance Fraser's ruling 'confirms our concern that he is not fit to do the job'. Neuberger replied that this 'sounds like par for the course'.

Grabiner reiterates this was not a personal matter but a view about the calibre of the Fraser judgment.

3.45pm: Before we go to a break, the inquiry sees an email where Grabiner accused Mr Justice Fraser of a 'rather pathetic attempt to dodge me' and saying his behaviour 'confirmed our suspicions about his Smith characteristics' (the Smith reference was to a Mr Justice Peter Smith who had recused himself on a different case four years earlier).

Beer asks: 'Was this becoming personlised?'

Grabiner: 'What do you mean by that?'

Beer: 'No more and no less than the question.'

Grabiner: 'Personalised between whom and whom?'

Beer: 'You and the judge.'

Grabiner: 'Me and which judge?'

Beer: 'The judge that you were applying to recuse himself.'

Grabiner: 'Absolutely not. My view was that he had made a mess of that case and that was my position and that was David Neuberger's view as well.'

3.40pm: As the decision was being finalised, Neuberger wrote to Grabiner: ‘I hope that they [the Post Office] do not bottle it. Apart from the PR front (where the arguments cut both ways in my view and anyway it’s all short term pizzazz) the argument for having a go at recusal is very strong’.

Grabiner replied to say that the Post Office had instructed them to proceed with the recusal application, adding: ‘I don’t think the clients had any choice but they were reluctant to take such a serious step.’

He tells the inquiry that unless they were comfortable with the legal advice the Post Office would not have taken this step.

3.30pm: Neuberger's email to Grabiner is shown to the inquiry. It makes clear he believes recusal is the only available option. Grabiner agreed with the opinions expressed.

3.20pm: Grabiner is asked why he did not want to see both sides of the argument before offering strong advice on the prospects of success in the recusal application.

He replies: ‘Basically all you need to do is to look at the judgment and find out what the issues were in the case that was to be decided, and whether or not the judge had gone beyond the matters that were supposed to be decided and whether he had trespassed upon matters which were yet to be dealt with in the other trials. That doesn’t involve a massive exercise and certainly doesn’t involve going through all the materials that were available in the trial.’

3.10pm: Inquiry sees Grabiner's email to Neuberger in which he repeats MacLeod's view that the Post Office board might have the 'stomach for a fight' because a recusal application was such a drastic step. He tells the inquiry that recusal was the only step available if the Post Office wanted any chance of winning subsequent trials overseen by Fraser.

Grabiner told Neuberger that he may be asked to advise without the counsel team on the call and added: 'I make no comment on that bollox.'

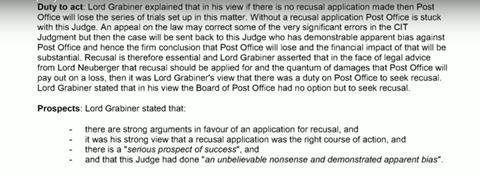

3pm: After a weekend in which the Post Office pressed Grabiner for a quick response, we see the outcome of his assessment (he had read the judgment by now). This is a note of a conference call in March 2019 between lawyers and the Post Office management in which Grabiner made clear that the organisation had a 'duty' to act and apply for recusal, adding that Mr Justice Fraser had shown 'demonstrable apparent bias'.

He added there was a serious prospect of success given the judge's 'unbelievable nonsense'.

2.50pm: Grabiner says he did not know who was driving the recusal bid but agrees that the Post Office felt ‘bruised and slighted by the judge’. He recalls being told by general counsel Jane MacLeod that the decision of Fraser in the first ruling had come ‘as a bolt out of the blue’ and no-one in the organisation had appreciated that such a strong view might be taken by the judge.

2.45pm: Grabiner was provided with a note from Post Office counsel and an initial opinion from Lord Neuberger (former president of the Supreme Court). Neuberger is not called as a witness to the inquiry, for reasons that have never been explained.

The inquiry hears that after reading these documents - but not the first Fraser judgment - Grabiner agreed there were reasonable grounds to apply for a recusal.

2.35pm: There was probably enough this morning to fill a whole live blog, but we go on this afternoon with another KC, Lord Grabiner. He was instructed by the Post Office for a second opinion on whether to apply for Mr Justice Fraser to recuse himself. This followed Fraser's first judgment on the Bates litigation in March 2019, which had gone against the Post Office.

1.25pm: Ed Henry KC (pictured below) presses on with the point about Robinson not referring directly to Jenkins misleading the court in his final submissions, suggesting that his explanation about Jenkins not being called was 'by no means the full picture'. 'I just don't agree with you,' says Robinson, who started the day leaning back in his chair but is now leaning forward.

Henry suggests Robinson was 'captive to your professional and lay client advancing again and again - inadvertently no doubt - misleading submissions to the court'. Henry asks why he did not challenge Post Office's instructions.

Robinson says the question is 'most extraordinary', adding that if one were to conduct complex litigation on the basis that the client needs to produce evidence to his barrister on every single thing, it would not be possible to draft a defence.

Robinson is now done. We break for lunch, with Lord Grabiner KC next in the witness chair this afternoon.

1.15pm: Beer has finished and hands over to Sam Stein KC (pictured below), representing some of the sub-postmasters. He asks straight away whether claimant lawyers were told that Gareth Jenkins had misled the court.

Robinson answers, but Stein says he is trying to divert from the question asked. Robinson is not happy with this, and inquiry chair Sir Wyn Williams has to step in to pull them apart (in a lawyerly way).

Stein asks again: Did claimant lawyers know - as Robinson did - that Gareth Jenkins had misled the court?

Robinson says the Clarke Advice, the source for this assertion, was produced six years before and was considered to be a privileged document that could not be shared.

Robinson says: 'I think you are reading too much into that. I am given sometimes to explaining things in a very colourful way.'

Beer: 'Suppression means to silence, to cover up, to conceal, doesn't it?'

Robinson: 'You are reading too much into that.'

Beer: 'I am just reading back the words that are recorded in this attendance note on you.'

Robinson: 'Do remember this is an informal conversation between litigators and I am speaking in an easy-to-understand and rather dramatic way. If you are going to put to me there was actually suppression of evidence because Gareth Jenkins was not called I would refute that suggestion.'

1pm: Then we see a lawyers' attendance note from after the trial had finished and before Fraser's judgment was delivered. Robinson and WBD were meeting with Herbert Smith Freehills who had been newly instructed by the Post Office. HSF asks if the claimants had tried to argue that information about bugs had been surpressed.

Robinson said that they had, adding: 'They made huge complaints that we didn't call Gareth Jenkins, who is a god but an unreliable god. They say that the fact we didn't call Gareth Jenkins is suppression. And you know what, that might be right. They would have killed him at trial.'

12.50pm: Beer really pushing at this suggestion that lawyers misled Fraser about the reasons for Jenkins not appearing. He states again that Jenkins was proved to be unreliable and gave false evidence, pointing out that none of this was explicitly referred to in the Post Office's explanation.

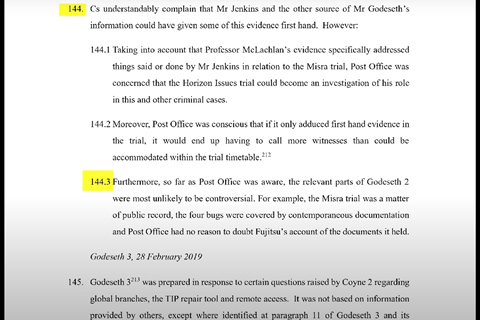

Robinson replies: 'Paragraph 144 signals to the judge [the reasons for not calling Jenkins]. It doesn't do so with the emphasis you would probably suggest is required but I do not accept that was misleading. In the eyes of an experienced litigator that would have signalled quite clearly what the real concern was.'

Beer looks aghast, responding: 'Really, you think that signals quite clearly? Is that really what you are saying?'

12.40pm: Back again, this time going to the Post Office's 500+ pages of closing submissions in the Horizon litigation, signed off by Robinson.

Beer takes the inquiry to this passage at paragraph 144 where the Post Office lawyers address Jenkins' absence from court. There is no mention of the Clarke Advice here or admissions about the privately-expressed concerns about Jenkins appearing at trial as a witness.

Beer asks whether the explanation provided here give the true reasons for Jenkins not being called. Robinson says it does. Beer follows up by asking whether Robinson and his team are being open and candid with the court.

Robinson replies: 'It was being made clear there were issues in relation to what Mr Jenkins had said or not said in criminal cases which would have become the focus of attention. In my view that gave a fair indication to the judge of the concerns that Post Office had.'

12.20pm: Despite Jenkins not appearing as a witness at the trial, he was working behind the scenes advising on aspects of Horizon. Robinson says he was dissatisfied at how Jenkins kept 'popping up'.

But despite the discredited witness' work on trial preparation, this involvement was not disclosed to the claimants, prompting heavy criticism from Mr Justice Fraser in his lengthy judgment. Fraser said Jenkins' work behind the scenes was 'simply hidden'.

Robinson tells the inquiry: 'To say I am cross [about the non-disclosure of Jenkins' involvement] is an understatement.'

He explains there was a protocol in place whereby every exchange between Fujitsu and the Post Office's nominated expert witness was to be witnessed and recorded by Womble Bond Dickinson. This in turn should have been disclosed to the claimant lawyers. Robinson says it should 'never have been possible' that Jenkins' role might not be disclosed and he is 'astonished' that it happened.

'Any failure to record the information [passed from Fujitsu] and provide that information to [the claimants] would have been Womble Bond Dickinson's failure,' adds Robinson.

The inquiry heads to a second morning break.

12.10pm: In the same case note, it is stated that claimant firm Freeths wrote in January 2019 asking why Jenkins was not a defence witness. The note records that lawyers responded ‘pointing out that Dr Jenkins had acted as expert witness in relation to a number of prosecutions that are being review by the CCRC and it was therefore not appropriate to call him’.

Robinson, who had not provided this information himself, admits this explanation was ‘economical with the truth’ and therefore false.

12pm: Beer asks Robinson to clarify why Jenkins was not called as a witness in the Horizon litigation. The KC agrees that Jenkins had given misleading evidence and had been in breach of his duties to the court.

But then this: contemporaneous case notes from Bond Dickinson (which by this stage had become Womble Bond Dickinson) admitting that it had been explained to Fujitsu that the Post Office did not want to call Jenkins 'because we did not want to mix civil and criminal justice'.

Beer suggests that if that explanation was given to Fujitsu then that was false. Robinson agrees, suggesting that the form of words was 'ambiguous'. Beer replies that it is a 'bit more than ambiguous' and that lawyers were, on this evidence, not providing a true reason for not asking Jenkins to appear.

11.50am: The big question was whether Jenkins should be called as a witness in the Horizon litigation. He was, after all, previously regarded as the biggest expert on the Horizon system and had been the only prosecution expert in dozens of cases.

In his witness statement, Robinson says he felt at the time that Jenkins was an 'obvious candidate' to appear as a witness for the Post Office.

But this changed after a meeting with Post Office's criminal firm Cartwright King.

Robinson says of this meeting: 'The upshot was that I was told in emphatic terms that Mr Jenkins was not a reliable witness. The solicitors said that Mr Jenkins had given misleading evidence. They suggested in no uncertain terms that I should be very cautious about calling him as a witness.'

11.40am: The inquiry hears that Robinson was only told about the Clarke Advice in 2018 - and only 17 days before the Post Office was due to file its defence.

Robinson says he was 'disappointed' by the process of evidence gathering and says it often felt like firefighting, adding that dealing with the Post Office was 'exquisitely painful' and made it difficult to do his job properly.

11.35am: We restart by looking back at the Simon Clarke advice from 2013, which was shown to Robinson when he was instructed by the Post Office. He concluded at the time that expert prosecution witness Gareth Jenkins had not complied with his duties to the court and had not disclosed his knowledge of bugs in the Horizon system. This was in ‘plain breach’ of his position as an expert and his evidence was flawed, meaning the Post Office was in breach of its duties as a prosecutor.

11.15am: General counsel Jane MacLeod wrote to colleagues in 2016 to say that given proceedings had been commenced by sub-postmasters, the Swift Review should be ended immediately, based on ‘very strong advice from external legal advisers’.

Beer points out the justification for this is not consistent with the email exchange between Parsons and Robinson. Robinson accepts this.

We go to a mid-morning break.

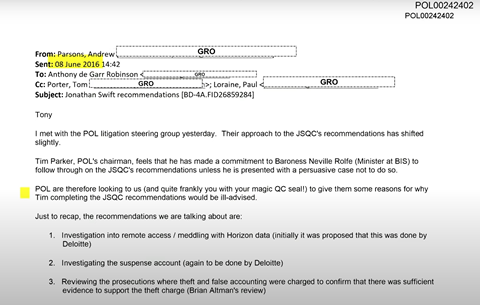

11.05am: Parsons responded at the time to say that it was critical to preserve privilege, concluding that it was a 'good enough reason to shut [Tim Parker] down'.

11am: Robinson says he cannot remember this email exchange but accepts Beer’s point that what is good for Post Office litigators is not necessarily good for the thousands of sub-postmasters or the general public.

In his email reply, seen by the inquiry, Robinson said from the outset: ‘I’m not here to provide political cover, but I am concerned that the client should protect its interests as a defendant to this substantial piece of litigation.’

He tells the inquiry: ‘I wanted to make it clear I am not interested in your political shenanigans.’

10.50am: The inquiry sees this email from Andrew Parsons in which he asks for help in persuading the Post Office not to act on recommendations of the Swift Review in 2016. This advice had found real problems with Horizon and recommended further investigation. But Parsons was worried about this affecting the proceedings brought by sub-postmasters and asks Robinson to offer some 'magic QC seal' to put the brakes on the Swift Review being followed through.

Parsons’ email concludes: ‘If we can give [Post Office] a piece of advice that says [chair Tim Parker] should stop any further work, [he] would then feel empowered to say to BIS that, on the basis of legal advice, he is ceasing his review. I’m conscious that this feels somewhat unpleasant in that we are being asked to provide political cover for [Parker]. However, putting aside the political background, shutting down [his] review is, in my view, still the right thing to do.’

10.40am: Beer pushes at this assumption that Fujitsu was the cause of disclosure failings rather than the Post Office, showing Robinson an email from the Post Office in response to questions he had posed about known error logs (the existence of which would clearly have benefitted the sub-postmasters' case). The Post Office said then that this data was not relevant and in any case outside of its control.

Beer suggests Robinson was 'straining' not to disclose this information. Robinson replies: 'I believed my instructions. I don't think I would have inferred there was any such attitude on my client's part... I remember being surprised [after the trial]. I would have been concerned that such a fundamental point could have been so wrong. [But] the focus of my concern would have been Fujitsu rather than Post Office.'

10.30am: In his witness statement, Robinson describes the Post Office approach to disclosure in the litigation as ‘extraordinary’. He unintentionally misled the court on several occasions as he said data was not available, when it was later disclosed. For example, it was only after the trial that the Post Office disclosed there were 5,000 known error logs with the Horizon system. Robinson says this was a ‘horrifying experience’.

Beer asks whether it was an uncomfortable thing to go through. Robinson agrees.

Beer then follows up: ‘When you found out what you were told was not the true position it must leave you not trusting your clients or solicitors?’

Robinson says the problems with disclosure were caused by Fujitsu. This was the explanation given to him by the Post Office and Bond Dickinson.

10.15am: Robinson wrote within a week of instruction to Andrew Parsons, from Post Office solicitors Bond Dickinson. He asked a series of pertinent questions, including whether shortfalls may show up without sub-postmasters causing them, and whether and when remote access was known about. Robinson accepts Beer’s assessment that Parsons’ responses were ‘relatively cursory’ and that Parsons did not answer the question about whether lawyers had looked into whether convictions had been unsafe based on the unreliability of Fujitsu’s expert witness Gareth Jenkins.

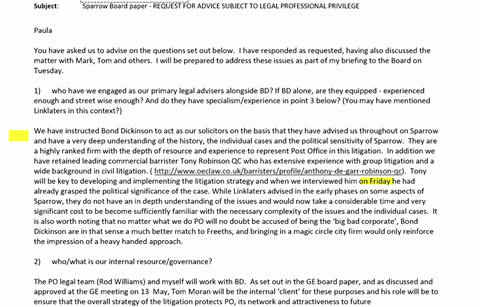

10.05am: The inquiry sees this email from MacLeod to chief executive Paula Vennells, talking about Robinson's potential instruction. The general counsel suggested Robinson had 'already grasped the political significance of the case'.

The KC tells the inquiry he is not clear what is meant by MacLeod's choice of words. 'I had certainly grasped there was a sense of concern and embarrassment that statements had been made about remote access,' he says. '[But] I would have regarded this as a piece of commercial litigation.' Robinson adds that he was never influenced by political issues in his decision-making on this case.

9.55am: Robinson was instructed following initial meetings with the Post Office and its general counsel Jane MacLeod in 2016, what inquiry counsel Jason Beer KC describes as a ‘beauty parade’ for the Post Office to decide which barrister to instruct.

At these first meetings the Post Office said it had previously denied that Fujitsu, the Horizon system operator, could gain remote access to branch accounts. That now appeared not to be correct, and Robinson advised the organisation to be open about this.

The KC says that the Post Office kept having to correct things that it had previously said, adding: ‘It was very frustrating at times.’

9.45am: A potentially big week in terms of lawyers’ role in the aftermath of the Post Office scandal, as the inquiry looks in detail at the Bates litigation and specifically the controversial and ultimately doomed attempt to have the judge handling the case recused.

First to appear will be Anthony de Garr Robinson KC, who represented the Post Office during the Horizon issues trial as part of the Bates v Post Office litigation. Then the inquiry will hear from Lord Grabiner KC, counsel who argued for the judge in that case, Mr Justice Fraser, to be recused.

Crucially, we will find out what counsel were instructed by their solicitors and by the Post Office legal team.