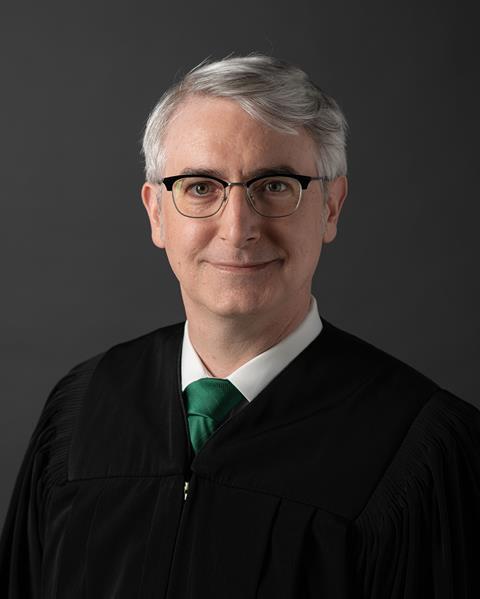

District associate judge for the state of Iowa

My path to becoming a solicitor began in university and continued through my career as an American criminal judge. In the spring of 1999, I was an aspiring photojournalism student at university when I enrolled in the most challenging course of my academic career: Media and The Law with Prof Barbara Mack. This course was renowned for its difficulty, as Prof Mack, a highly accomplished media lawyer, employed a rigorous Socratic teaching method. I was also exposed to my first serious analysis of free speech guarantees and the constitutional foundations. The class was enthralling and inspired a passion to pursue a career in law.

Several years later, I shifted to law school, where I encountered challenging coursework and rewarding internships. Among these, my favourite was a prosecuting internship, where I honed my skills in criminal trial litigation, handling both bench and jury trials. Upon passing the bar, I secured a position as an assistant prosecutor.

For the next 11 years, I specialised in prosecuting white-collar and vehicular homicide cases. Later, I became a judge, serving various roles in criminal courts. For comparison, my jurisdiction here in Iowa encompasses aspects similar to half of the Crown court, all of the magistrates’ court, and small claims appeals.

Leaving prosecution was a difficult choice because it was fulfilling. However, I was reminded by a colleague that the best time to switch careers is when you are content with your job, aiming for growth rather than escape from an unrewarding career out of desperation.

Becoming a judge was the right choice, though it posed the risk of professional stagnation, common in judicial careers with limited upward mobility. After a couple of years, I sought professional enrichment in other ways, first considering the barrister route like my friend and mentor, Nick Critelli, an Iowa lawyer and bencher of Middle Temple. Due to my current judicial career, the year-long pupillage requirement made it impractical. The solicitor route emerged as a more feasible option, offering both challenge and qualification in another country.

'Many aspects of UK law could benefit American practitioners... the pre-action protocol is an intriguing tool'

When I began studying, I simply wanted to see if I could pass SQE1. I approached preparation like any other hobby. For almost a year, I set aside one hour of free time per day to work through modules and practice questions.

Over time, studying for SQE1 became enjoyable as I explored new legal approaches. While we share many similar common law principles embedded in contracts, torts, and wills, there are other stark differences. For instance, in American criminal law, the right-against-self-incrimination is solidified in the Fifth Amendment of the Bill of Rights, while in the UK, exercising silence by a defendant can lead to an adverse inference at trial, a concept that still personally bothers me.

Furthermore, the concept of parliamentary sovereignty, where Supreme Court declarations of incompatibility do not overturn government acts, is confounding. In contrast, American courts, over 200 years ago, empowered themselves to reverse the government when laws conflict with our enumerated constitution.

Many aspects of UK law could benefit American practitioners. For instance, the pre-action protocol is an intriguing tool. Currently, in the US, prelitigation letters often go straight into the bin. Adopting some of these rules with consequences for non-compliance could lead to faster, fairer outcomes for clients.

After a year of self-study, I took the SQE1 exam in New York City, one of only two available locations in north America, and more than a thousand miles from home. Testing in London was not an option due to jet lag’s potential effect on my test performance. The SQE1 proved to be the most challenging test I’ve ever taken, much harder than the Iowa bar exam. Convinced I had failed, I anxiously waited six weeks for the results. To my astonishment, I passed. When it came time for SQE2, I discovered that I was exempt due to my prior years of practice. Although tempted to take the test for the experience, I ultimately chose to accept the easy pass after considering the associated costs.

Becoming a solicitor has enhanced my abilities as a judge. Studying the law of England and Wales has sharpened my focus on finer details of American law. While my immediate goals do not involve practising abroad, my aim is to foster international legal connections between the UK and my home. This collaboration will enable us to learn from each other and enhance both of our justice systems.

No comments yet