Generative AI such as OpenAI’s GPT series offers opportunities for law firms to streamline data extraction and administrative tasks. But the legal sector also needs to be wary of the pitfalls of entrusting data to third-party technology

Last week, I was in New York meeting US legal tech luminaries and attending America’s largest legal tech conference. As in the UK, the biggest buzz is around generative AI, and specifically OpenAI’s ChatGPT – a real-time natural language model that produces cogent text instantly in response to questions. The excitement was heightened further by the latest iteration of OpenAI’s GPT series, GPT-4 passing the bar exam with flying colours.

Generative AI is breakthrough technology. But in respect of trusted professions like law it still requires human guidance and has already generated a new (human) skill – prompt engineering, or asking the right questions to produce useful and appropriate output. And law firms are among the first organisations recruiting prompt engineers.

ChatGPT is not infallible. On 20 March it experienced a significant outage after a bug exposed brief details of users’ chats to other users. And although OpenAI’s website advises users against sharing sensitive information, last week’s incident is a warning to the legal sector in particular to consider the implications of entrusting data to (even the latest) third-party technology.

On 27 March, investment bank Goldman Sachs concluded that if generative AI lives up to its promise, it will bring significant disruption to the labour market, exposing around two-thirds of workers in major economies to AI automation. While most workers would see less than half their workload automated, the paper identifies lawyers and administrative staff as among those at greatest risk of redundancy.

Legal in the vanguard

It follows, therefore, that the legal sector, which is traditionally slow to adopt new technology, has been quick off the mark when it comes to learning about and working with generative AI. The fact that in recent years legal tech has seen firms increasingly use AI for data analysis and extraction, and document/contract automation, as well as administrative tasks like client onboarding, has enabled it to hit the ground running.

A LexisNexis survey, ‘2023 Generative AI & The Legal Profession’, conducted in mid-March and published last week, found that US legal professionals are generally more aware than the general public of generative AI tools such as ChatGPT, with 88% having heard of them (compared with 57% of consumers surveyed), and half of these were either using it in their work or planned to do so. The survey identified five applications of generative AI in lawyers’ daily work: increasing efficiency, researching matters, drafting documents, streamlining work and document analysis.

Avoiding hallucinations

LegalWeek’s AI sessions covered practical use cases for generative AI in legal which engages via a conversational interface, but presents potential pitfalls; notably ChatGPT’s tendency to ‘hallucinate’ or invent references to cite in its responses. In one panel, Aaron Crews, chief product and innovation officer at ALSP (alternative legal service provider) UnitedLex, described it as a ‘moderately bright, but very lazy first year associate’. He was referring to GPT-4’s factual accuracy of around 80%, which is clearly not acceptable for legal work. However, the latest applications in legal apply GPT to verified datasets and include human supervision to address this challenge.

Jasper for legal

Wexler is an early-stage start-up founded by Gregory Mostyn. He is participating in Entrepreneur First, a tech incubator in London backed by high-profile investors including LinkedIn founder Reid Hoffman. Mostyn saw generative AI as an opportunity to build a tailored content creation tool to help lawyers write articles, memos, letters and briefs. Wexler’s platform will include recent case law analysis, where judgments are classified by key words and topics that lawyers can draw on, using generative AI to create personalised commentary. Wexler generates a first draft that can be used as a framework for internal and client updates, website articles and other business development content. ‘Our global vision is to become Jasper for legal, repurposing content to help mid-size firms compete effectively with larger firms with more resources,’ explains Mostyn. Wexler is currently in beta and looking for mid-size firms to pilot and help develop the product (wexler.ai/home).

NextGen chatbots and contract analysis

Generative AI has breathed new life into legal chatbots. Several new offerings in the e-discovery and contract lifecycle management (CLM) space are leveraging ChatGPT and GPT-4 to enable lawyers and clients to interrogate large datasets and contracts in real time. For example, ContractPodAI’s GPT-powered chatbot Ask Leah responds to queries related to contracts. Similarly, e-discovery vendor DISCO launched DISCO Cecilia. This is a chatbot which combines large language models (LLMs) with proprietary technology, replacing the need to search and review documents with the ability to ask and get answers to specific questions.

Other use cases for generative AI include document drafting, analysis and review, legal research and knowledge management, content creation (initial drafts and summaries), and contract analysis and automation.

However, there are doubts about GPT-4’s ability to improve on established legal AI for document analysis and automation. I met Noah Waisberg, founder of Kira systems (now owned by Litera), one of the first legal applications to use machine learning, and Zuva, a contract/document analysis tool for businesses. The Zuva team recently conducted an experiment, applying GPT-4 to standard contract analysis tasks. They found that although it was generally competent, its output was inconsistent, particularly on change of control clauses, which can be phrased in different ways. The conclusion was that while ‘GPT-4… appears able to do a lot very well… we are unconvinced that it yet offers predictable accuracy on contract analysis’. They added the footnote: ‘In situations where accurate contract review really matters, we recommend using contract analysis AI in conjunction with a user interface that includes a document viewer.’

A strategy of combining GPT with other platforms and applications is reflected by the development of GPT-powered legal chatbots to augment CLM and e-discovery platforms, and by OpenAI’s decision to extend ChatGPT’s reach with third-party plug-ins to external sources. OpenAI’s own plug-ins include a web browser via the Bing search API (previously ChatGPT was limited to web data up to September 2021, which compromised its accuracy) and a code interpreter (e.g. for mathematical problems, data analysis and visualisation, and converting files between formats).

'Our global vision is to become Jasper for legal, repurposing content to help mid-size firms compete effectively with larger firms with more resources'

Gregory Mostyn, Wexler

Data structure and standards

The effectiveness of any AI depends on the data it is trained on and applied to. So applying generative AI to validated data sources – a firm’s data, client data, and external sources like court data, Westlaw and LexisNexis – protects its accuracy. However, when it comes to deal diligence and e-discovery, even unstructured data has to be findable. We are therefore seeing renewed focus on data management and classification.

Tim Anderson, senior managing director at global business advisory firm FTI Consulting (which recently expanded its partnership with AI e-discovery platform Reveal to include global data hosting and early case assessment), reiterates how technically complex these data challenges are. While many legal teams are aware of the issues, they are often stumped at how to resolve them in active matters. Issues like short-form message processing, linked content and version control of dynamic, cloud-based documents are arising on more and more matters. Without detailed, technical attention to these issues, many downstream issues can arise, Anderson explains. ‘Highly regulated clients in financial services are looking for expertise around data privacy, compliance and managing risks around multiple third-party platforms, like WhatsApp, Teams, and Zoom where there is a lack of visibility into the underlying data,’ he adds.

Standardising classification

An interesting development in the US that could potentially be replicated elsewhere is a new tool developed by the Standards Advancement for the Legal Industry (SALI) Alliance. This is a non-profit group that has developed a universal framework to classify legal data. As Damien Riehl, VP of litigation workflow and analytics content at Fastcase, and one of the leaders at SALI explains, SALI’s open source tags for matters, documents and tasks are used by legal services providers, legal tech vendors and their clients. SALI has been working with Daniel Katz and Michael Bommarito (authors of the study where GPT-4 passed the bar exam) on a GPT-4 tool that enables organisations to automatically classify their data, as well as their own taxonomies, with SALI tags. Once extracted, the SALI tags permit analytics and interoperability with SALI implementers (for example, Thomson Reuters, LexisNexis, NetDocuments and many others).

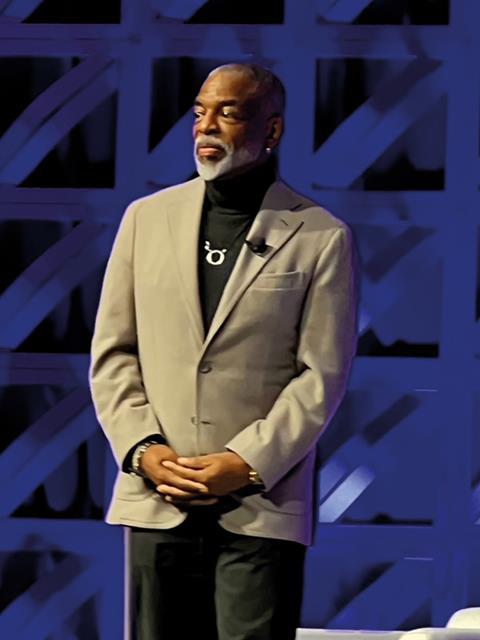

Legalweek’s final keynote featured Dan Schulman, CEO of PayPal, who said that leadership comes down to two things: the ability to define reality and inspire hope. GPT may be inspiring hope across the US legaltech community, but is it yet able to define reality well enough to be genuinely transformative? The answer, probably, is not yet. Katz underlines the importance of structuring/preprocessing data (as per the SALI model) and deciding between general LLMs and more specialised domain-related models. As legal tech vendors and start-ups scramble to include GPT in their models, it is important to determine the value they add to a technology that will soon provide direct access via Microsoft platforms and applications.

1 Reader's comment