In what will be a year of significant change, looking at legal tech through a quadrant model can help firms focus on new developments that will help their business strategy

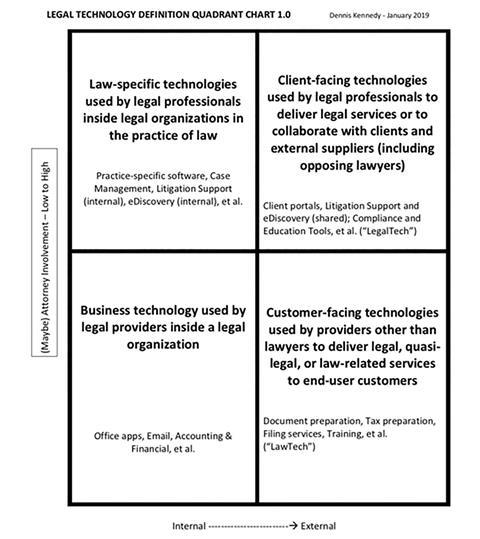

Professor Dennis Kennedy, adjunct professor of law at Michigan State University College of Law, teaches a class called Delivering Legal Services as part of the LegalRnD programme. Kennedy uses the quadrant model below to explain legal technology to his students:

Rather than making predictions or analysing with hindsight what happened to last year’s predictions, Kennedy’s legal tech quadrant model inspired me to look at legal tech through the lens of another quadrant model: the well-known BCG matrix (pictured, right), a framework for portfolio analysis and planning developed by Boston Consulting Group.

The X axis is (relative) market share; the Y axis is market growth rate; and products are divided into four quadrants: Stars (high growth rate, high market share); Question Marks (high growth rate, low market share); Cash Cows (low growth rate, high market share) and Dogs (low market growth rate, low market share). Looking at legal tech products through the lens of this market maturity model shows what is gaining traction in the market, and what is losing market share, and how the dial is shifting at different rates for different products, vendors and purchasers.

The first few weeks of 2019 have seen consolidation, acquisitions and divestments. Global law company Elevate added Halebury, Yerra Solutions and Hong Kong-based Cognatio Law to its portfolio, which includes LexPredict, which it acquired last November. LexisNexis announced the sale of its enterprise resource planning (ERP) system LexisOne to SAGlobal. Thomson Reuters is ‘sunsetting’ its client relationship management system 3E Business Development, both of which are built on Microsoft Dynamics. Meanwhile, both Thomson Reuters and LexisNexis have launched incubators, so while they are discontinuing longstanding products, they are jostling for the next game-changing ideas.

The BCG model is not static: Question Marks develop into Cash Cows or Stars which eventually become Cash Cows, and Cash Cows that are replaced by new products soon become Dogs. While law firms’ tech spend is rising exponentially, the pace and dynamic at which products shift between the quadrants reflect how product lifecycle feeds into business strategy and adoption rates generally.

As Ian Jeffery, chief executive of Lewis Silkin, explains, legal tech is no longer just about ‘lights-on’ technology and efficiency improvements. Some firms are strategic investors, so timing is critical. A key decision is when to invest in new products, such as artificial intelligence (AI), and then whether to be an early adopter and invest in an early-stage product, so that you can help shape it to your requirements and train it on your data; or whether to invest later, when any initial problems have been ironed out. If you want your firm to be a first mover, do you invest in an incubator that develops new ideas that might bring competitive advantage, or back a single product that fits your strategy?

For example, Slaughter and May back Luminance, whose AI software is used by law firms and legal departments to process large volumes of documents without having to engage an external outsourcer, or employ more people (even temporarily). So it is particularly useful for firms that wish to extend their business without increasing their numbers. Luminance is currently valued at £100m following a second funding round, which included Slaughter and May, so the latter is benefiting both from the technology and from being an early investor in a successful product.

Another discussion point is the changing role of the law firm IT function. As legal tech spend has increased, it has potentially breached the IT director’s remit in several places. Jeffery highlights the significance of cloud computing, which has shifted legal tech to Software-as-a-Service products which do not require on-site maintenance.

‘Until recently, legal tech was all about infrastructure, but the work was done by humans,’ says Derek Southall, head of innovation and digital at Gowling WLG and CEO of consultancy Hyperscale Group. ‘The industry is being hit by a wave of productivity-focused start-ups, but most firms are still moving their infrastructure to the cloud.’ And the latest offerings require different skills. ‘For example, an iManage RAVN implementation requires legal and sector knowledge and an understanding of how the algorithm works, neither of which are traditional IT skills,’ says Southall.

Martyn Wells, IT director at Wright Hassall, sees his role as delivering technology that boosts Wright Hassall’s customer service, rather than a straightforward technical lead.

The first six weeks of 2019 saw ‘Big Law’ recruiting legal tech ‘disrupters’ into innovation roles. Baker McKenzie hired high-profile consultants Casey Flaherty and Jae Um. Flaherty, former corporate counsel at Kia Motors, developed the Legal Tech Audit to test lawyers’ tech skills. Um was director of strategic planning and analysis at Seyfarth Shaw, before founding strategic market research and analysis consultancy Six Parsecs. Christian Lang, creator of NY Legal Tech Meetup (similar to Jimmy Vestbirk’s original Legal Geek) became head of strategy at Reynen Court, a Big Law-funded technology consortium. Perhaps the legal elite recognises that you need a winning team to lead the way in legal innovation. Or perhaps they are influenced by tech giants: Apple, Facebook, Microsoft and Adobe regularly acquire popular software products, and then decide whether/when to develop them further. This way they control the pace of change in the market, until something groundbreaking appears. Is Big Law looking to lead innovation, or control its pace?

‘If I tell my firm’s customers that we have great AI tools, they will want to know how these will affect the price of our services,’ he says. ‘If I tell them that our collaboration technology means that they can talk to a lawyer at 6pm and we can produce and deliver a draft document straight away, they will want to buy legal services from Wright Hassall. The IT function’s role is to align our technology with the services we provide.’ Wells sees ‘client-facing technologies used by legal professionals’ as tomorrow’s Cash Cows – as legal ERP systems decline. He adds that vendors are discontinuing legacy business technology tools (see Kennedy’s model) which are losing market share because ‘their Cash Cows have been milked dry and they have not reinvested in product development’.

‘Buying trends are also changing,’ adds Wells. ‘While 15-20 years ago IT functions routinely handled big IT implementations, now we are using apps to facilitate productivity and knitting together best-of-breed applications. Firms are looking at smaller-scale deployments like Office 365, collaboration tools, and AI and machine learning.’

Wells maintains that technology is still key to competitive advantage. The new Cash Cows are cloud-based apps and collaboration systems. Like all online products and services, they are predicated on delivering customer expectations.

The biggest challenge remains operational, as firms and vendors struggle to combine solutions. ‘Most law firms are ready and willing to change,’ says Southall. ‘But the legal tech market has gone from famine to feast in a very short time. IT projects have changed too – they now require lawyer input. Because these new tools go under the skin of legal service delivery, they require legal and sector expertise.’

Some products are weathering the storm, because they are central to the business, and also because they are adapting to the changing market. For example, the document management system (DMS) is central to the business because it holds its intellectual property – documents, emails, precedents and so on – whereas practice management systems and case management software are business technology – workflows and databases – which is interchangeable.

DMSs are Stars because they continue to develop and grow, and they have high market penetration. A limited market (in the UK around 250 firms) dominated by just a few vendors (in the UK by iManage and NetDocuments) makes it difficult for competitors to enter the space.

In law-specific technology, such as content curation and document/contract automation and analysis, LexisNexis and Thomson Reuters retain a solid position as Cash Cows with high market penetration. This is likely to continue as they add tools such as predictive analytics to their offerings. Promising Question Marks that are evolving into Stars include AI-powered Luminance, Kira Systems and ROSS Intelligence and iManage RAVN’s AI-powered document classification and extraction application.

A big Question Mark is the dynamic between platforms and start-ups. While some vendors are divesting and discontinuing platforms, others are launching ‘app stores’. Platform vendors and big firms are looking to acquire start-ups, and start-ups are looking to combine and develop complementary activities so that they can become platforms.

At the start of 2019, the legal tech landscape remains in a state of perhaps unprecedented flux.

1 Reader's comment