With its remit greatly expanded by Brexit, is the Competition and Markets Authority up to the job? Maria Shahid reports

The low down

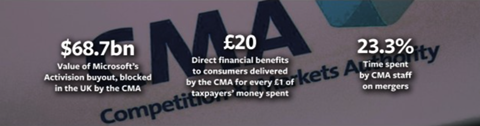

When the Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) blocked Microsoft’s $68.7bn takeover of Activision, Microsoft’s wrath earned it a one-to-one meeting with chancellor Jeremy Hunt. That is not quite the government support the CMA might have hoped for as an independent regulator taking on new responsibilities post-Brexit. Still, if the Digital Markets, Competition and Consumers Bill becomes law, consumer protection will be enhanced and the market power of the most powerful tech companies limited. The effect could be ‘seismic’, representing the ‘most significant changes since the advent of the “modern” competition regime’. Is post-Brexit UK competition regulation fit for purpose? We are in the process of finding out.

The regulator charged with promoting competition in the UK, the Competition and Markets Authority (CMA), has, in the words of executive director Dr Michael Grenfell, been through turbulent times. Just two and a half years after its formation, in 2014, Britain voted to leave the EU – and the CMA’s role and function grew to encompass areas previously reserved to the European Commission.

Fast forward to the present day, and the regulator’s role is now about to grow even further. Anti-trust/competition watchdogs in the UK and globally are taking a tougher stance on Big Tech.

Inevitably, this has increased the already heavy workload of competition lawyers, particularly those acting for tech companies. New, tighter regulation of the market is imminent. ‘Our work as competition lawyers has been on an upward trajectory since Brexit,’ notes Addleshaw Goddard partner Al Mangan.

In a speech in mid-June, Sarah Cardell, chief executive of the CMA, spoke of the regulator’s role in sustaining UK innovation by promoting competitive markets. ‘Dominant businesses can distort incentives for smaller firms in the same ecosystem, and their own incentives to innovate may be reduced,’ she said.

The CMA’s decision to block Microsoft’s $68.7bn buy-out of Activision earlier this year, over fears that it would lead to the former assuming a dominant position in the UK cloud gaming market, came after the same deal received the green light from the EU. This led to claims by Microsoft president Brad Smith that the CMA was undermining confidence in the UK as a destination for tech businesses.

Cardell, however, maintained that the regulator is pro-innovation, citing Meta’s acquisition of Kustomer and Microsoft’s acquisition of Nuance as just two examples. ‘There is no doubt in my mind that the fundamental connection between competition, innovation and growth is at the heart of the CMA’s work,’ Cardell concluded.

Microsoft has filed a legal challenge to the CMA ruling, which is due to be heard in late-July. The tech giant has five grounds of appeal, including that the CMA failed to properly consider the various cloud gaming agreements it signed with competitors before the CMA’s decision.

In a surprise twist, Microsoft’s Smith met chancellor Jeremy Hunt earlier this month to try and broker a compromise. The meeting came following comments made by Hunt at the British Chamber of Commerce annual conference in May. While acknowledging the importance of an independent regulator, Hunt noted the importance of ‘all our regulators understand[ing] their wider responsibilities for economic growth’. So much for a policy of regulatory independence.

The power of online platforms is causing concern more widely. The EU’s Digital Markets Act, which came into force on 1 November 2022, regulates powerful digital firms designated as ‘gatekeepers’.

Last November, Hunt confirmed in the autumn statement that the government would bring in new legislation to protect consumers from fake reviews and subscription protection, as well as giving the CMA new powers to deal with anti-competitive practices in digital markets.

While the CMA created a Digital Markets Unit (DMU) in April 2021, with the core objective of overseeing digital markets, promoting greater competition and innovation, this has so far operated on a non-statutory basis. Legislation currently making its way through parliament is putting it on a statutory footing. The Digital Markets, Competition and Consumers Bill (DMCC) published in May seeks to enhance consumer protection and limit the market power of the most powerful tech companies. Those with a global turnover of over £25bn, or a UK turnover of over £1bn, will fall within its scope.

‘It’s a seismic change for the sector,’ notes Mangan. ‘It will mean a whole new regime for an industry used to operating in an unregulated way, and it will take some adjustment.’

‘It is important not to underplay the importance of the changes,’ observes Stevens & Bolton partner Gustaf Duhs. ‘Taken as a whole, they are probably the most significant changes since the advent of the “modern” competition regime in the UK over 20 years ago.’

For businesses falling within the scope of the rules, the DMU will have the power to designate individual companies as having strategic market status (SMS). This will allow the DMU to impose a code of conduct, regulating the firm’s activities and imposing sanctions should the organisation breach the code’s requirements. The DMU will be able to fine a company 10% of their annual turnover if the code is breached.

The unit’s powers extend to imposing ‘pro-competitive interventions’ where it considers markets not to be working well. This allows it to make a number of changes, such as forcing structural separation of different parts of an SMS firm.

The regime changes will require firms designated as gatekeepers (under the EU regime), and with strategic market status (under the UK regime) to undertake significant work to ensure compliance, say competition lawyers. Furthermore, the regulations will also be of relevance to organisations that interact with powerful digital firms.

Experts note that the DMU’s powers are more of a ‘precision instrument’ than the position under the EU regime, allowing for a more bespoke, tailored approach to individual circumstances.

Dr Aysem Diker Vanberg is a lecturer in law at Goldsmiths, University of London, specialising in competition law, data protection and digital markets. She explains that digital companies which are designated as having strategic market status will need to be careful in their conduct or face substantial fines. She notes that the UK’s approach is more nuanced and cautious than that of the EU.

She adds: ‘The CMA’s power to make a “pro-competition intervention” where, following an investigation, it has reasonable grounds to consider that there may be an adverse effect on competition in the UK, is an interesting feature. The CMA having this power may lead to a quicker resolution of competition issues.’

Lawyers warn of the importance of ensuring compliance with different regimes for companies operating across borders. Professor Suzanne Rab, a competition law barrister at Serle Court, observes: ‘As a point of difference, it’s important to understand that in the EU regime, once an organisation is designated as a gatekeeper there will be a uniform set of rules. The CMA by contrast can tailor its requirements, and so a global business could be subject to diverse requirements in the EU and UK.

‘For markets which are by definition borderless, such as digital services, there will need to be a careful consideration of the jurisdictional range of the rules. You may have to comply with the highest standard.’

Some competition lawyers believe that the two regimes should be able to work in tandem. Ashurst partner Anna Morfey says: ‘With the EU’s Digital Markets Act (DMA) entering into force this year, platforms will begin to be designated, so it is helpful to have further insight into the proposed UK regime as companies will need to carefully consider both regimes when adapting their internal compliance policies.’

She adds: ‘The UK’s more tailored approach to codes of conduct should allow for requirements under the DMA to be reflected, which will help to minimise the risk of conflicting obligations. We expect the CMA will be a proactive regulator and make significant use of the new tools available to it once the [digital markets bill] enters into force.’

‘Don’t let law deter innovation’

The Competition and Markets Authority carried out a consultation earlier this year on draft guidance relating to the applicability of competition law to agreements between competitors in relation to environmental sustainability agreements.

The Competition Act 1998 prohibits agreements between businesses that restrict competition, known as the Chapter I prohibition.

The guidance reflects the CMA’s increasing focus on net zero and sustainability, as set out in its draft 2023/24 annual plan.

The regulatory body is currently carrying out ongoing ‘green-washing’ investigations relating to potentially misleading environmental claims being made to consumers.

Appeal process

Some controversy has surrounded the appeal process in relation to decisions of the DMU. Lawyers acting for tech companies have voiced concern about the government’s decision to favour judicial review as the appropriate appeal mechanism, which it believes will be quicker than a merits-based system. This will mean that the Competition Appeal Tribunal will only be able to overrule the DMU on grounds such as procedural fairness, error of law and irrationality, and not because it considers the decision to be wrong.

‘The Bill envisages a considerable degree of judgement will be afforded to the CMA in the strategic market status designation process,’ says Rab. ‘The combination of these factors means that the scope for appeal will be relatively narrow and where the tribunal may be expected to show a degree of deference towards what will usually be a complex evidence-based decision of the CMA, as an expert authority.’

Jonathan Jones, former head of the Government Legal Department and a senior consultant at Linklaters, has argued that the view that a judicial review will be a quicker and more agile process than a system of appeal based on the merits is an oversimplification. Given the significance of the decision, there is a strong case for ‘subjecting those decisions to a standard of appeal that allows the tribunal to determine whether the decision is “materially wrong’’’, he has noted.

‘The approach to the standard of review reignites the debate about whether a judicial review standard in competition and regulatory appeals is a proper check and balance for the rights of defence,’ says Rab. ‘In the last decade the pendulum has shifted towards a preference for this standard in regulatory appeals. A judicial review is still realistically possible on issues such as an unfair hearing or failure to take into account relevant considerations. But the historic approach favours leaving decisions of expert regulators on substance undisturbed.’

Consumer protection in the spotlight

The Digital Markets, Competition and Consumers Bill also gives the CMA new consumer protection enforcement powers. Central to this is the introduction of a new ‘administrative enforcement model’, allowing the CMA to issue infringement decisions. This contrasts with the current regime whereby the CMA can only accept undertakings or make a court application for an enforcement order.

The Bill will also allow the CMA to impose penalties for a breach of undertakings and for any procedural breaches during a CMA investigation.

This is likely to lead to an increase in investigations for consumer breach, say lawyers. Morfey explains: ‘Bringing the CMA’s powers to enforce consumer law in line with its competition law enforcement powers will have a significant impact on the UK’s regulatory landscape, and we anticipate a substantial increase in the number of investigations in consumer law breaches.’

This really cuts across any interaction between a business and its consumer, notes Osborne Clarke associate director Katrina Anderson: ‘We’ve suddenly got this enforcement regime being proposed, which means the whole process can be quicker. It will really change the way companies will think about consumer protection, as infringing the rules will have a much higher risk for them. There are two aspects to this. Historically, they will need to look at how they are currently interacting with consumers and they will need to make sure that they have processes in place to ensure compliance.’

She adds: ‘This is going to do for consumer protection what the GDPR did for data protection. It will really focus companies’ minds.’

Existing consumer rights have also been updated in four core areas to take account of online shopping, including fake reviews and subscription traps (where consumers sign up to free or low-cost trials which are then auto-renewed, or do not alert to the end of a trial period, or otherwise make it difficult to cancel a subscription).

‘It’s a really big change for my clients, especially for tech platforms that offer any type of a subscription service,’ says Anderson. ‘There is a lot of scrutiny of all things digital at the moment, and the DMCC is a part of that.’

‘There are still a number of unanswered questions when it comes to reviews,’ she notes. ‘We were expecting specific offences which didn’t come to pass, so there may be a separate consultation on that.’

Lawyers warn that overseas companies will also be affected by the changes, to the extent that they have a place of business in the UK, carry on business in the UK, or the conduct at issue arises in the context of carrying on activities directed to consumers in the UK.

Seismic change

The Bill is expected to receive royal assent next year, giving tech companies likely to be affected time to get their house in order, say experts. Pinsent Masons partner Alan Davis says: ‘Given the strategic market status designation process takes nine months, with a possible three-month extension, and… the CMA will also have to develop and consult on bespoke conduct requirements for each designated firm, the new digital markets rules are unlikely to become fully applicable until 2025.’

Ashurst partner David Futter concludes: ‘Companies should familiarise themselves with the thresholds for SMS status and be prepared, if applicable, to support the DMU’s investigations.’

Maria Shahid is a freelance journalist

1 Reader's comment