Solicitors want to help vulnerable people get the advice they need to challenge injustice, reports Catherine Baksi. But worsening poverty is bringing the malign legacy of the ten-year-old LASPO legislation into ever sharper relief

The low down

For people living in poverty, the pandemic, cost-of-living crisis and civil legal aid cuts have created a perfect storm. Although families no longer need to fear the Poor Laws and the workhouse, the law and the way it is administered can make their lives even harder when they are faced with issues like debt, eviction, or benefit sanctions. Advice deserts created by the shortage of legal aid lawyers and overstretched law centres mean many are not getting the help that they need to prevent legal problems escalating – or to challenge wrong decisions made by government agencies.

About one in five people in the United Kingdom were living in poverty in 2020/21, according to figures from social change thinktank the Joseph Rowntree Foundation – that is 13.4 million individuals. Of those, 7.9 million were working-age adults, 3.9 million were children and 1.7 million were pensioners.

In the midst of a profound cost-of-living crisis, some are having to make difficult choices about what they spend their limited funds on as they struggle to make ends meet. Many are also still grappling with the aftermath of the pandemic.

Before the development of the welfare state which emerged after the second world war, poverty was dealt with by the Poor Laws. Initially, poor relief was administered at local parish level, until the 1834 Poor Law created a more centralised system with the large-scale development of workhouses.

The new Poor Law ensured that the poor were housed in workhouses, and clothed and fed at a basic subsistence level. Children who entered the workhouse also received some schooling. In return for this basic level of care, workhouse paupers had to work for several hours a day in what were essentially penal conditions.

While those living in poverty today no longer have the fearful spectre of the workhouse hanging over them, they face desperate and pressing issues, including eviction and homelessness, clothing and feeding themselves and their families, and associated health problems.

The law, which should be used as a tool to support those in need, too often works to their detriment, compounding the impact on wider society.

Until 2013, the civil legal aid system provided a vital safety net for thousands of people who had been let down by the law or those administering it, as well as for people facing employment, housing, debt and family law problems.

But the Legal Aid Sentencing and Punishment of Offenders Act 2012 (LASPO), which came into effect 10 years ago this month, removed whole areas of law from the scope of public funding.

The number of legal aid cases to help people get the early advice they need dropped from almost a million in 2009/10 to just 130,000 in 2021/22. Since 2010 funding for civil legal aid has fallen by about a third.

Over the same period the number of advice agencies and law centres doing this type of work has fallen by 59%. Others have been forced to close and many law firms have also shut their doors.

Low fee rates that have not increased for two decades mean that remaining providers are struggling to recruit the next generation of social welfare lawyers. This has resulted in large advice deserts, with millions of people living in areas where they cannot access the legal help many need and to which parliament has said they are entitled.

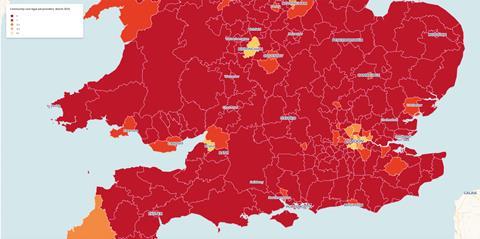

Maps produced by the Law Society show that across England and Wales, 53 million people (90%) do not have access to a local education legal aid provider; 49.8 million do not have access to local advice on welfare benefits; 42 million (71%) do not have nearby community care advice; and 25.3 million do not have access to a local legal aid provider for housing.

In addition, some of the poorest individuals and families are being denied legal aid because they cannot afford the financial contributions that they are required to make by the eligibility means test. The situation has been getting progressively worse because, while the means test has not changed in over a decade, the cost of living has risen dramatically.

Earlier this year, the government announced a review of civil legal aid, but this is not scheduled to publish any report until 2024. As Lubna Shuja, president of the Law Society, says: ‘A decade on from LASPO, civil legal aid is facing an existential crisis. The survival of these services is in the balance. People can’t get the legal support they need when they need it.’

Contracting woes

According to solicitors, the way the Legal Aid Agency manages its tenders and contracts exacerbates the problems caused for clients by the shortage of advice providers. As a result of the review announced last October, officials extended the 2018 standard civil contracts. This meant that new providers were unable to apply for contracts in some areas of work.

Solicitor Siobhan Taylor-Ward (pictured) joined Vauxhall Law Centre in Liverpool in January 2021. She intended to start a housing department to provide pro bono help under grant funding and do publicly funded work. But the contract extension meant that the centre was unable to obtain a contract.

Says Taylor-Ward: ‘At the same time, the number of providers and solicitors operating in Liverpool and Merseyside has shrunk.’ She explains that the organisation that used to operate the Housing Possession Court Duty Scheme at Liverpool county court went into administration before Christmas, leaving Shelter, Merseyside Law Centre and James Murray Solicitors to cover the duty rota between them. None of these organisations has more than two full-time housing lawyers.

When organisations band together to cover the duty scheme, she explains, it reduces their capacity to take on any other cases. In addition, the law centre is having to advise people in possession proceedings without legal aid because they have been unable to obtain a solicitor.

‘The lack of legal aid is preventing people fighting their cases in some instances, or leaving them at risk of costs in others,’ she warns.

In February the Legal Aid Agency was forced to re-tender a dozen housing legal aid contracts after receiving no bids.

A high-profile recent report by Roger Smith and Nic Madge proposes the creation of a National Legal Service to bring together under common branding existing advice providers – as well as new methods of advice provision.

It also calls for a large injection of cash from government as well as alternative funding streams, including the controversial idea of a levy on the profits of City law firms.

Aside from the move by the coalition government to restrict access to advice via LASPO, Chris Minnoch, director of the Legal Aid Practitioners Group, argues that there are many other ways in which the law and bureaucracy have been misused to the detriment of people in need.

His long list includes ‘deliberately putting administrative barriers in place’, for example regarding the evidential requirements for obtaining legal aid in family law cases involving domestic violence.

Minnoch also cites the ‘overly-stringent and pernickety means evidence requirements; mandatory telephone gateways; ludicrous exceptional case funding application requirements; changing merits thresholds; and giving unqualified civil servants the power to make decisions and overrule experienced legal practitioners’.

The way that the legal aid funding rules transfer the risk to advice providers is also problematic, says Minnoch. He gives the example of solicitors undertaking judicial review claims getting paid only if they succeed in securing permission to pursue a matter.

The Ministry of Justice maintains people are entitled to a service, says Minnoch, when in reality administrative hurdles deter clients, frustrate applications and force providers to withdraw from publicly funded work.

He also criticises the ministry’s failure to gather data to assess the scale of unmet need. ‘If you don’t measure need it cannot be proven that you are failing to meet need,’ he observes.

For many who cannot afford a lawyer, law centres provide one of the few available avenues of assistance. Their caseloads show just how badly some of the country’s most vulnerable citizens are being let down.

'A tenant, who was not in rent arrears, approached the receivers and asked if she could stay at the property, but was informed that they would seek possession unless she was able to buy the property'

Hugh Wilkinson, Central England Law Centre

Housing is one of the biggest problem areas. In common with others, Derbyshire Law Centre reports a high demand for housing advice, and has seen a particularly big rise in the number of mortgage repossession cases.

Central England Law Centre, meanwhile, is seeing increasing numbers of tenants being evicted due to landlords defaulting on their mortgages. In some instances, the mortgage company has appointed receivers following a landlord’s default.

‘In these cases the mortgage company’s objective is to get a quick sale with vacant possession to recover their losses,’ explains Hugh Wilkinson, the centre's head of housing law.

He gives an example: ‘We were told that a tenant, who was not in rent arrears, approached the receivers and asked if she could stay at the property, but was informed that they would seek possession unless she was able to buy the property.’

In other cases landlords have not obtained the mortgage company’s consent to let a property. In that eventuality, Wilkinson adds, tenants cannot prevent the mortgage company obtaining a possession order if the landlord falls behind on the mortgage, even if they themselves have done everything they need to under the tenancy agreement. All they can do is ask for eviction to be postponed for a couple of months.

Requests for debt advice are also high, but the number of advisers is wholly inadequate, confirms a spokeswoman for Derbyshire Law Centre. This has created a widening gap in the market for unscrupulous companies charging for advice and assistance from unqualified people.

Central England reports that decision-making by the Department for Work and Pensions is making things worse for many. More and more clients on universal credit are being forced to rely on food banks and social supermarkets, and falling further behind with rent and bills, says David Beckett, head of welfare and benefits law at Central England Law Centre.

He reports ‘an alarming number’ of people becoming subject to ‘unfair universal credit sanctions’ – deductions from their benefits payments for a set period as a result of a failure to meet the ‘claimant commitment’ or ‘work-related requirement’.

‘In our experience, almost all sanctions can be successfully challenged, which means that full benefits are reinstated or refunded,’ he says. Of course, clients need advice and advisers to enable this.

An internal DWP report published earlier this month, which the government tried to suppress, revealed that benefit sanctions could slow down claimants’ progress into work and result in them taking lower-paid jobs, leaving them even worse-off.

The Commons work and pensions committee first asked for the DWP’s analysis of the effectiveness of benefits sanctions in 2018. A DWP spokesperson said: ‘Sanctions – 97.6% of which are applied when claimants fail to attend mandatory appointments – are measured and proportionate. They ensure fairness runs through the system, both for claimants and the taxpayer, and it’s important to note this report does not assess sanctions’ deterrent effect.’

The spokesperson added: ‘Conditionality is a cornerstone of our support with sanctions designed to encourage people to meet certain commitments, preparing them for workplace responsibilities. Most claimants agree this makes them more likely to look for work or take steps to prepare.’

Law centres are also dealing with increasing numbers of people subjected to repayment programmes because of overpayments made by DWP. In some cases, these overpayments run into thousands of pounds, says Beckett.

‘Often, the claimants have repeatedly flagged the overpayments to work coaches in their journal and they’ve been ignored, so overpayments have continued,’ he adds.

The real-life impact of civil legal aid cuts was brought into particularly grim relief last November, when coroner Joanne Kearsley concluded that toddler Awaab Ishak died from a respiratory condition caused by exposure to mould in the one-bedroom Rochdale flat where he lived. His father, Faisal Abdullah, had complained to the landlord, Rochdale Boroughwide Housing over three years, but no action had been taken.

Barrister Christian Weaver was part of the legal team representing the family. ‘When it comes to disrepair, legal aid is only available if a tenant can prove there’s a serious risk of harm to their health or safety,’ says Weaver. That, he explains, creates a problem because in the majority of disrepair cases the family or individual will not get legal aid and will not be able to challenge a landlord’s failure to remedy issues.

‘If landlords know that the reality is that the tenant won’t be able to go to court, it promotes a culture where they don’t fix issues,’ says Weaver, who wants to see eligibility for legal aid increased.

Another ominous development is the ending of the government’s Energy Bills Support Scheme on 1 April, which gave millions of eligible households £400 off their energy bills in six-monthly instalments. This has been replaced by the Energy Bills Support Scheme Alternative Fund, which targets around 900,000 eligible households that did not receive money under the earlier scheme.

Law centres report that they are already seeing people in serious difficulty. A spokeswoman for Derbyshire says: ‘We have come across numerous examples of energy providers taking huge amounts out of people’s bank accounts – where they have a direct debit – but where the energy provider says they need to pay more. Sometimes money is taken out of an account and people are left destitute with no money for food.’

This comes in the wake of concerns raised about magistrates issuing thousands of warrants allowing energy firms to break into people’s homes and forcibly fit prepayment meters which operate on a more expensive tariff than direct debit payments. In February, Lord Justice Edis, one of the country’s most senior judges, told courts to halt the authorisation of warrants due to concerns over vulnerable customers.

A statement from the Magistrates’ Association said there may be a case for reviewing the law here, but stressed that this is a matter for parliament.

‘Magistrates’ role is to apply the law – the Rights of Entry (Gas and Electricity Boards) Act 1954, the Gas Act 1986, and the Electricity Act 1989 – as it stands to everyone equally,’ it said.

Once a debt has been established, the association insisted that magistrates ‘have no choice but to issue a warrant’.

In summary, a Ministry of Justice spokeswoman said that in the last year the government has spent £813m on civil legal aid and made a series of changes to eligibility.

In addition, she said the government has recently invested an extra £10m a year into housing legal aid, enabling thousands more people to access advice.

Officials also stressed that legal advice on a range of civil matters including housing, debt, discrimination and education is available through the Civil Legal Advice telephone service.

Something is always better than nothing – but that civil legal aid review cannot come to a conclusion soon enough.

Catherine Baksi is a freelance journalist

1 Reader's comment