As law enforcers fight a multi-faceted battle against fraud, Grania Langdon-Down looks at the revolutionary challenges posed by cryptoassets to solicitors on the frontline

THE LOW DOWN

Frauds involving cryptocurrencies are now valued in the billions. While the courts are discomfited by the technology and the involvement of pseudonymous or anonymous defendants, they are willing to use the flexibility of common law tools to recover assets. That said, a litigator faced with cryptocurrencies, a bank account and a house will go for the bank account and the house first. For all that cryptocurrencies and blockchain have set the courts a demanding intellectual problem, the key issues in a civil claim remain the interplay with criminal law, problems with disclosure and the cost of pursuing assets. And moving ever more quickly is paramount.

With law enforcers swamped by the ever-rising tide of fraud, victims are increasingly turning to civil courts and specialist practitioners to trace and recover assets, and obtain some form of justice.

At the same time, key developments concerning cryptoassets mean that UK courts are leading the way in trying to keep pace with fraudsters now that funds can disappear at the touch of a button.

Yet there are significant risks associated with the interplay between the civil and criminal routes. Huge cost consequences can ensue if there are failures in the civil approach – for instance if a freezing order is discharged because disclosure has not been ‘full and frank’.

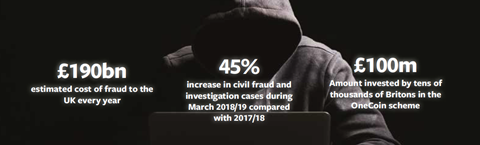

Fraud costs the UK an estimated £190bn a year, but last summer a Times investigation uncovered damning revelations about the way Action Fraud, the UK’s fraud reporting centre, treated victims. City of London Police promised an ‘immediate examination of standards’.

Daniel Machover is head of civil litigation at Hickman & Rose, representing both defrauded victims pursuing civil remedies and defendants being sued for alleged fraud. He sees the issues from both standpoints.

Fraud cases can become a ‘legal minefield’, he notes, with multiple claimants and defendants, and subject to criminal and civil proceedings in the same or different jurisdictions.

Given the poor record of law enforcers in investigating and prosecuting fraud, Machover says victims may have a better chance of tracing and recovering assets by pursuing the fraudsters through the civil courts.

‘But they will need to move quickly in circumstances where they will clearly be reluctant to spend thousands of pounds for fear of adding irrecoverable legal costs to the money taken by the fraudster,’ he stresses.

‘However, depending on the circumstances, the potential to apply quickly for a freezing order could be more effective than waiting weeks for the police to begin an investigation, while the fraudster puts the money out of reach.’

But, he warns, civil actions can create problems for later criminal proceedings. ‘Issues that need constant vigilance include maintaining legal privilege, protecting the privilege against self-incrimination, and securing relevant material. In some cases, civil actions can give rise to arguments by criminal defendants that the criminal case is an abuse of process.’

An analysis of UK commercial courts by Portland found there was a 45% increase in civil fraud and investigation cases during 2018/19 compared with 2017/18. It is now the third most common type of litigation, with UK and Kazakhstan cases topping the list (115 and 27 litigants respectively).

The report says that, despite the UK government’s increasing scrutiny of high-profile Russian, Kazakh and Ukrainian nationals, London remains the forum of choice for litigants from these jurisdictions. Cases continue to involve oligarchs and billionaires often residing in London, with some facing worldwide freezing orders (WFOs) and jurisdiction challenges.

While freezing orders are dubbed the law’s ‘nuclear weapon’, Keith Oliver, head of international at Peters & Peters , says international litigants choose UK courts because they value the system’s reputation for fairness and integrity.

The UK is also prepared to take a global lead in developing the law. Last November, the UK Jurisdiction Taskforce, part of the industry-led LawTech Delivery Panel, published a statement that cryptoassets have all the legal characteristics of property and should, as a matter of English law, be treated as property.

CIVIL FRAUD MUST SHED ‘MACHO’ CULTURE

A fraud, asset tracing and recovery conference being held in Geneva in March includes a workshop on leading high-performing teams through diversity and inclusion – ‘the good, the bad and the grey areas’.

There is a need, says Kingsley Napley partner Mary Young, for the industry to diversify and ensure its culture is inclusive. Three of the five partners in her team who specialise in civil fraud are women.

‘The irony is that diversity is rarely reflected in conferences and public events,’ she says. ‘At one recent event, not only did the sponsor have more speaking slots than all the women put together – each one of their speaking slots was filled by a man.’

‘Civil fraud is one of the less diverse areas of law if you look at the legal directories and it historically had an image of being quite macho, with long hours and aggressive litigation.’

But this is changing, she says. ‘I think having women in leadership roles means other women think, OK, this is manageable. But I also think that having a mixed leadership means you have different perspectives and less risk of unconscious bias.’

A group of solicitors with civil fraud practices – Kate Gee and Juliet de Pencier from Allen & Overy; Charlotte Pender and Caroline Greenwell from Charles Russell Speechlys; and Pia Mithani and Elaina Bailes from Stewarts – has set up the ACROSS network as a forum for leading practitioners of the future to share experiences and knowledge.

Unveiled by Sir Geoffrey Vos, chancellor of the High Court and chair of the UK Jurisdiction Taskforce, the statement is the first step to conferring full legal status on cryptoassets and smart contracts – agreements using the blockchain technology that underpins cryptocurrencies and assets. ‘This is something no other jurisdiction has attempted,’ he said.

The aim of the statement is to provide investors with ‘increased confidence of their rights’ and ‘a dependable foundation for mainstream utilisation of cryptoassets and smart contracts’.

‘This is real British ingenuity,’ says Oliver, ‘in saying to the world at large that cryptoassets are property as a matter of English law. It sounds very simple, but I would suggest this is one of the most important developments in the legal application of technology since the internet was invented.

‘By vesting property rights in crypto, it will now simply be a matter of using the existing tools we have in the UK’s legal toolkit, already utilised in remedying the theft of “traditional” property, to cross apply to cryptocriminality.’

Cryptocurrency is already proving a breeding ground for fraud, given its decentralised nature and a lack of regulation. Tens of thousands of Britons invested about £100m in the OneCoin scheme and are among victims from 175 countries in what US prosecutors have alleged is a £4bn Ponzi fraud.

Speed is critical in locating, freezing and recovering stolen cryptoassets. But the concern for practitioners has been the intangible nature of cryptoassets such as bitcoin, which is merely information or data, and whether this created a property right.

The courts have been stepping up to the challenge. At the start of the year, the Singapore International Commercial Court held in B2C2 v Quoine Pte (2019) that cryptocurrencies do meet all the requirements of a property right and can be the subject of a trust.

Relying on that authority, Marc Jones, who leads the cybersecurity team at Stewarts, obtained an asset preservation order (APO) for bitcoin worth more than £1m stolen in a personally targeted ‘spear phishing’ attack and transferred to a digital wallet held by the UK arm of the San-Francisco-based digital currency exchange Coinbase.

The judge, Mrs Justice Moulder, had strong reservations about granting a freezing order: ‘We know nothing about this person who perpetrated the fraud. We do not know his identity. We do not know his assets. We do not know if a freezing order would achieve anything whatsoever.’

However, she found that an APO was an option because the court only needed to be satisfied that there was a serious issue to be tried concerning a proprietary claim.

For Jones, last August’s interlocutory decision in Robertson v Persons Unknown, marked the start of the English courts grappling with a new asset class that ‘is not going away’, opening the door to an effective remedy where a traditional freezing order may not be feasible.

The case also involved blockchain intelligence experts, with Chainalysis tracking down the bitcoin. Director of communications Maddie Kennedy says Chainalysis has evolved over the last five years from a bitcoin forensics startup to working with more than 140 cryptocurrency businesses and financial institutions, as well as governments in over 20 countries.

It was the lead investigator in the hack of the Japanese bitcoin exchange Mt Gox in 2014 and, on the investigations side, primarily works with law enforcement agencies and regulators.

‘In terms of cryptocurrencies used for illicit activity,’ Kennedy says, ‘0.4% of the transaction value across 27 of the cryptocurrencies that we support is sent to an illicit entity – for instance as ransomware, darknet markets, exchange hacks. While that may seem like a small percentage [it was equivalent to] approximately $3.8bn from January to October 2019.’

Mary Young is a partner specialising in civil fraud and asset recovery with Kingsley Napley’s dispute resolution team. She says the next important step in relation to cryptoassets was publication of the decision in Vorotyntseva v Money-4 Ltd (T/A Nebus.com) and others [2018] EWHC 2596 (Ch).

The High Court granted a freezing order against a company and its directors in respect of an amount of cryptocurrency which the claimant had given to the defendants. On the evidence before the court, there was a real risk of dissipation.

Oliver says his firm has yet to go after cryptoassets. ‘We always ask if they are involved,’ he says. ‘Blockchain is creating completely new legal problems and the stars of tomorrow will be the people who understand this today.’

When it comes to tracing and recovering cryptoassets, Ros Prince, co-head of Stephenson Harwood’s fraud and asset tracing team, says: ‘Frankly, a litigator faced with cryptocurrencies, a bank account and a house is going to go for the bank account and the house first.

‘Strategic decisions around asset-tracing are not purely based on what can be done legally, but what can be done to ensure that it’s cost-effective. It is troubling that some cryptoassets are difficult to trace but, where there is a significant fraud in the civil context, it is likely the fraudsters will have other assets to go after. ’

An issue still to be decided is whether a court will grant a proprietary injunction over a cryptoasset. ‘I suspect the courts will find a way if the right case comes up,’ Prince says. ‘This is the wonder of our system – that the courts work on precedent and so have a degree of flexibility in the interests of justice. They aren’t hampered in the way a more codified system would be. So, if someone nicks £100m and puts it into cryptocurrency, I would expect the court to find a way, whether by way of a freezing order or a receivership over the defendants’ rights, to call for that property.’

A key characteristic of cryptocurrencies is the pseudonymity or anonymity they confer on users.

While the judge in the Robertson case had strong reservations, the courts are showing a growing willingness to grant freezing orders against ‘persons unknown’. Building on CMOC v Persons Unknown [2017] EWHC 3599, the High Court reaffirmed in World Proteins KFT v Persons Unknown [2019] 4 WLUK 35 that interim freezing injunctions are able to be granted against persons unknown.

Young says: ‘I think that reflects the growth in cybercrime, where you know the account but not the name on it and so any immediate action is going to be against a “person unknown”. These cases show the courts are willing to address cybercrime and make novel judgments to help victims.’

The same approach will be taken with cryptoassets, Young believes. While anyone can access the blockchain distributed ledger and see the address to which a cryptoasset has been transferred, the difficulty comes in finding out who is associated with that address.

While worldwide freezing orders can be hugely effective, there have been recent cases where they have subsequently been overturned.

In a case involving a sovereign wealth fund, Republic of Angola and seven subsidiaries v Jose Dos Santos and others [2018] EWHC 2199, Mr Justice Popplewell discharged a $3bn proprietary injunction and WFO against 20 defendants for non-disclosure.

YACHTS AND PICASSOS

When trying to recover assets, there is a ‘sliding scale’ of the ideal asset to go after, says Ros Prince, co-head of Stephenson Harwood’s fraud and asset tracing team.

The easiest is money held in a UK bank account. ‘You can get a freezing order and know that the bank will not allow that money to be moved,’ she says.

The next best is UK real estate – thanks to HM Land Registry. ‘Fraudsters do sometimes create fraudulent or backdated mortgages or claim there is a trust over the property,’ Prince says. ‘But the question then is – why didn’t you register it?’

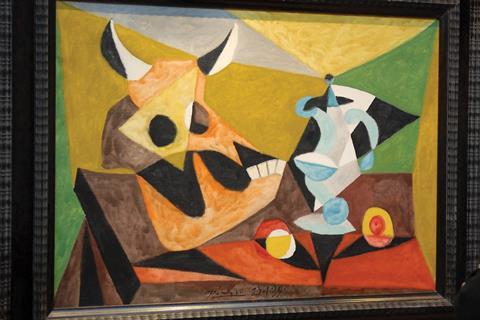

Shares in a UK company are ‘quite good’, but they can be transferred fairly easily. ‘Artwork is great if you can execute an order and grab it – finding a Picasso on someone’s wall is great. But until you have control, it is very easy to move and doesn’t have to be registered. Yachts are also easy to move but, equally, fairly easy to track.

‘The absolute nightmare of any asset tracer were bearer shares, which are still used in some jurisdictions,’ she says.

So where do cryptoassets come in the sliding scale? In August, the first asset preservation order was granted over £1m of bitcoin stolen in a spear phishing attack.

However, Prince says: ‘When you look at that continuum where the priority is the ability to find, freeze and seize an asset, we are some years away from anything “techy” becoming a huge issue in asset recovery cases.

‘It is going to be expensive for people to set new case law and go after those assets and get a return. At the end of the day, clients want to know that, once they have spent money on litigation, there is going to be a recovery.’

Prince says the issue of disclosure is genuinely very difficult, because everything has to be disclosed that is potentially relevant. ‘But, on the other hand, a judge isn’t going to want to sit in an ex-parte hearing for a week,’ she says.

‘Leaving aside the very rare cases where there is an intentional misleading of the court, there are difficult judgement calls to be made about what is so fanciful that it shouldn’t be flagged and what is relevant. It seems to me that the trend from the court is to look more carefully at whether all the boxes have been ticked.’

Young does not believe courts are ‘kicking back’ against freezing orders: ‘The courts are making it clear that failure to meet the basic threshold – a good arguable case and real risk of dissipation – will be critically analysed.’

It may also be that, because more freezing orders are being sought, there are more reported cases of them being set aside.

‘Freezing orders are the envy of many jurisdictions,’ she says, ‘because they also compel defendants to disclose what assets the defendants have, where they are held and in what form.’

Unless the defendants can challenge the order before the disclosure date, all their assets over a minimum sum will have been disclosed, whether or not the order is subsequently upheld.

‘It is not called the law’s “nuclear weapon” for nothing,’ she says.

But the approach can backfire. Claimants have to give a cross-undertaking in damages for a freezing order to be enforced. If there is loss suffered as a result of a wrongly obtained freezing order, the defendant is entitled to ask the court to enforce the undertaking. Losses can be very significant and ‘stigma’ damages can also be recoverable.

The Court of Appeal confirmed the court’s approach to issues of causation where a defendant applies to enforce a cross-undertaking in damages in SCF Tankers Ltd (formerly Fiona Trust & Holding Corp) v Privalov [2017] EWCA Civ 1877. The claimants, who were seeking damages of $850m, ended up being ordered to pay over $70m to the parties they had sued.

‘If I am advising a client about a freezing order,’ Young says, ‘this is the case I would refer to as the absolute horror story. It may be there will be more claims to enforce cross-undertakings in the pipeline over the next few years.’

While freezing orders in criminal trials can make it hard for defendants to pay their legal fees, Prince says the standard form for a freezing order in civil proceedings makes an allowance for legal fees because it is important the order is not used to stop someone defending themselves.

‘The relatively rare proprietary orders generally don’t include a legal expenses provision. In those cases, the claimant is arguing that the defendant took the asset and shouldn’t be allowed to use parts of it to fund their defence.’

The insolvency regime can also be a ‘potent weapon’ in obtaining information in fraud investigations, but it is often overlooked, says Paul Johnson, senior associate at Peters & Peters.

‘The private examination of the insolvent facilitator of a fraud and their associated parties can be ordered under section 366 of the Insolvency Act 1986,’ he explains.

‘There is also an overarching duty for the insolvent party to cooperate fully, while the act also provides the ability to launch an inquiry into a company’s business. Although it is often forgotten, this can, in certain instances, be applied extra-territorially, so it can be critical when tracing assets stashed overseas. These powers can all add real teeth to the process of uncovering/remedying fraud, but are often underutilised and their scope underestimated.’

With so many civil fraud cases involving assets held internationally, the question arises of whether Brexit will affect practitioners’ ability to trace and seize assets.

Oliver says ‘rumours of the collapse of the English legal system are hugely exaggerated. Once English courts are released from the limits of EU regulations, they will have greater discretion. The greater threat is from Singapore, not the English-speaking commercial courts being set up in Europe.

‘I also don’t think Brexit will affect our ability to trace and recover assets. I don’t believe EU regulations made tracing and recovery any easier. Have you ever tried to enforce a freezing order in Spain? Don’t ever do so in August, because basically it is closed.’

Grania Langdon-Down is a freelance journalist

No comments yet