Lawyers take pride in protecting the rights of disabled clients, but the profession’s own record on access is mixed. Are attempts to change that paying off? In the first of two features investigating disability and legal careers, Katharine Freeland reports on the position of trainees and junior lawyers

The low down

It is four years since Cardiff Business School, in partnership with the Law Society’s Lawyers with Disabilities Division, published their seminal report Legally Disabled. Based on the experience of disabled students and lawyers, the report identified barriers to entry into the profession for a wide range of disabilities. It also set out possible solutions. Lawyers calling for change acknowledge there has been progress. Yet too often, disabled people still do not have a clear pathway into the law and do not receive the support to succeed. The billable hours culture and its prioritisation of timesheets over team-building remain a substantial bar. Do entrenched attitudes and the traditional law firm hierarchy discourage juniors from telling bosses what they need to perform at their best?

Within the legal profession, disability has too often proved the poor relation within diversity, equality and inclusion efforts. In the quest to make the profession equitable for all entrants, disability has lagged behind ethnicity and gender. Legally Disabled, a 2020 joint report by Cardiff Business School and the Law Society ’s Disabled Solicitors Network (then the Lawyers with Disabilities Division), highlighted problems with the profession’s attitudes towards disability. An important marker, the report created recommendations for ways in which all firms – whether high street, boutique or City – could improve. Four years on, despite some creative and commendable initiatives and awareness-raising, there remains much to be done.

Like any profession, law’s ‘gateway’ – its access to qualification – is of central importance. The demands and restrictions of qualification set the character and makeup of each cohort.

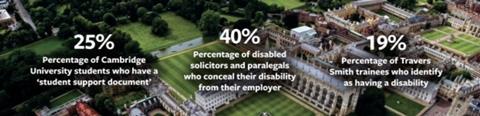

As the profession looks for aspiring lawyers, it sees a cohort of students within which disabilities are better recognised and understood. For example, around 25% of the current cohort across all disciplines at Cambridge University have a student support document. Many of Generation Z, even when academically outstanding, require a different approach to thrive. This requires a bold reappraisal of traditional working culture and entrenched attitudes in the law.

‘Cambridge University provides a wide range of support to students who

identify as having disabilities, but it is important to remember that considering individual adjustments when needed is beneficial for everyone,’ says legal academic professor Pippa Rogerson, Master of Gonville & Caius College. ‘No one knows when they might fall ill and require support.’

Changing world

There is important Solicitors Regulation Authority guidance on promoting disability inclusion and the requirements of the Equality Act for accommodating disabled people in the workplace.

‘The SRA guidance is theoretically helpful,’ says Paul Bennett, partner at professional regulation firm Bennett Briegal, ‘but good management and having the right policies in place is vital.’

Creating a welcoming space for potential trainees with a disability to apply, and then flourish, at the outset of their legal careers is essential. Yet those firms doing the bare minimum need to take stock of the expectations of the up-and-coming generation – particularly as the pandemic ensured flexible working became a widespread necessity. Law firms were able to quickly accommodate the needs of the individual in the workplace.

In the open

Disability in the workplace is notoriously difficult to define, with many disabilities hidden and undeclared. This is particularly so in the legal profession. Legally Disabled reported that 40% of disabled solicitors and paralegals did not identify themselves to their employers for fear that they would experience stigma and career disadvantages. Such reticence is a

possible reason why disability has been absent from many DEI initiatives. ‘A culture of openness and support emanating from the very top of the firm’s hierarchy is crucial in encouraging more junior staff to communicate their needs more effectively’, says Penny Morrison, a solicitor at boutique employment firm Osborne & Wise.

The Equality Act defines disability as ‘a physical or mental impairment’ which ‘has a substantial and long-term adverse effect’ on a person’s ‘ability to carry out normal day-to-day activities’. It can cover anything from severe physical impairment to neurological conditions such as autism or ADHD.

It is important to note too that a person’s disability can fall under the Equality Act and require ‘reasonable adjustments’ even if they do not consider themselves to be disabled. Many students who identify as having a disability fall into the category of having mental rather than physical disabilities – such as ADHD, autism, anxiety and depression – conditions which require ‘soft’ rather than ‘hard’ reasonable adjustments by an employer.

‘The legal profession in general is more confident in making “hard” rather than “soft” adjustments, because “soft” adjustments require careful consideration of law firm culture and established team dynamics,’ says Reena Parmar, counsel in the global transactions practice at Freshfields Bruckhaus Deringer. Parmar is the founding member and former co-chair of Freshfields Enabled, the firm’s UK disability resources group, and chair of the Law Society’s Disabled Solicitors Network (DSN).

First steps for firms and students

For law firms

- Perform a thorough audit of all training, recruitment and application processes, to ensure that these consider disabled people throughout and have no negative impact on them. In Legally Disabled, the move towards online application processes in recruitment and training was raised as a particular concern by some disabled participants. Employ a disability consultant if possible, as they will be best placed to evaluate your provision. Working with partners such as MyPlus Consulting, EmployAbility and Aspiring Solicitors can open up pathways to the recruitment of disabled solicitors.

- Implement a disability leave policy to enable disabled people to take time off work if they need it.

- Examine whether your website is accessible and easy to use for those with visual and other impairments. Consider how website assistive technology could help.

- Are your premises accessible and is this clearly signposted when people come for an interview? According to Legally Disabled, addressing accessibility should not just involve wheelchair access, but factor in a range of physical, sensory or learning impairments. In the report, when asked how easy it was to find out about the accessibility of a prospective employer, less than 1% of the solicitors and paralegals surveyed found it ‘very easy’ and 7% ‘fairly easy’, with 60% expressing concern that inaccessible working environments limited their opportunities.

- Facilitate placements and work experience opportunities for disabled applicants, including the introduction of reserved work experience and training places for disabled candidates.

- Provide peer support in the form of a disability network. ‘We have found storytelling to be a very powerful tool in engagement,’ says CSR and diversity director Chris Edwards about Enable, the disability network at Travers Smith. Role-modelling from disabled partners is also really important.

- Encourage outreach to support disability organisations.

- Consider the disabled candidate in all of your messaging. Offers of an interview, work experience, or invitations to events should include details of the support available and provide a named contact for further information and questions. ‘Few organisations these days would hold an event that served food without asking about people’s dietary requirements; it needs to become as commonplace to ask people if additional adjustments are required,’ says Legally Disabled.

For law students

Websites: For disabled students contemplating a legal career, the first points of contact are often the recruitment and DEI pages of law firm websites. Several years on from Legally Disabled there are some excellent examples of clear signposting and messaging for these potential recruits. But it is often a challenge untangling disability from the broad spectrum of DEI data to establish whether an application from a disabled candidate will be welcome and their needs supported.

If the website lacks substance on the nature of disability support – such as a disabled affinity group, targeted outreach or mentoring – but you are still interested in working for the firm, consider notifying the graduate recruitment contact. Some firms do not publicise the support they provide, or disability support measures may be in the pipeline and not yet in the public domain. Smaller firms may provide support to the individual on request, rather than rolling out an initiative. The worst-case scenario is that the firm has neglected to consider disability as an essential component of an effective DEI offering, but it is worth investigating further if you like the firm and the work.

Work placements: Applying for work placements at various firms will allow you to experience working practices first-hand, meet the people, assess the firm culture and ask questions.

Peer support: Consider joining groups, such as the Law Society’s Disabled Solicitors Network (DSN) to share knowledge, help further their initiatives and gain an insight into which firms are committed to supporting disabled lawyers.

Look at flexible working provision: When comparing firms, ask about their strategies for flexible, part-time or remote working. Are they a participant in Project Rise? This cross-firm initiative from the DSN seeks to encourage more part-time training opportunities. Legally Disabled and others have identified flexible, part-time and remote working and training contracts as central to the inclusion, retention and advancement of disabled people in the profession. With more firms demanding time in the office, it is important to seek out firms which recognise that flexible working allows a wider pool of diverse talent to build successful careers.

Generation gap

Since the publication of Legally Disabled, attitudes towards disability at the entry point of the profession have changed. DEI data is a crucial tool. It shows that today’s disabled trainees take a very different approach to their predecessors. At City firm Travers Smith, 19% of trainees identify as having a disability. This is compared with 10% of partners and 13% firm-wide. ‘It is a generational shift,’ says Chris Edwards, CSR and diversity director at the firm. ‘New entrants are more open about what they need, having been provided with support in schools and universities.’ Travers is one of the few City firms that does not have chargeable hours targets (another is Slaughter and May). Targets were a factor identified in Legally Disabled as a practice that clearly disadvantages disabled people. The removal of such targets means that lawyers are not forced to compete with each other for work, arguably fostering a more collegiate approach. Taking the time to investigate a law firm’s culture and working practices is important when weighing up training contract applications.

Increased candour between trainees and their employer means support can be provided at the very start of careers, rather than trainees having to ‘put their hand up’ – possibly multiple times as they move seats. ‘The earlier the question “how can we help you?” is posed, the better,’ says Millie Hawes, head of Just Purpose at Fieldfisher. Hawes is a former disabled activist who heads the firm’s disability network Discover and leads initiatives to remove barriers to inclusion. ‘It lifts the veil and makes it OK to have that conversation about what support is required from the earliest possible stage,’ she says. Hawes often attends recruitment fairs to answer questions from law students. The firm also includes named contacts for disability and neurodiversity queries in all recruitment materials.

The recruitment process should be as accessible for those with disabilities as it is for other candidates. At Reed Smith, cognitive aptitude tests in its graduate recruitment scheme were abolished and replaced with an untimed behavioural strengths assessment. This is designed to limit discrimination against disabled applicants, such as those with dyslexia or autism, who might experience heightened anxiety during a timed test. Firms should also consider whether the use of artificial intelligence in assessments might use ableist assumptions and criteria that would disadvantage disabled candidates.

Everyone’s invited

Extending the simple question ‘how can we help you?’ beyond disabled trainees to everyone at the firm reaps dividends, reducing the stigma for people who need to request adjustments. It also helps to identify best practice for other groups, creating a happier workplace and elevating client service. ‘It is a very easy win to include this in interviews and appraisals,’ says Chris Seel, diversity and inclusion adviser at the Law Society. ‘But those asking need to know how to respond to the answer or when to take it away and revert.’

As seen in the Travers Smith statistics, there is a considerable generation gap when it comes to identifying as disabled. This means a lack of disabled role models at partner level. Recognising the importance of support for colleagues at all levels, Freshfields now offers a neurodiversity diagnosis to everyone – an important step to aiding self-knowledge, raising awareness and creating role models for the next generation of partners.

‘Having successful disabled role models is crucial,’ says Parmar. ‘There aren’t enough of them across the full spectrum of seniorities in the legal profession at present, although things are slowly changing.’

The need for reasonable adjustments may fluctuate over the course of a career, so continuous dialogue is important. An example of sustained support is a scheme by TLT called ‘Enabled Employee’. It aims to give all employees who need specialist assistance a clear understanding of what support is available from the recruitment stage and beyond. This includes knowing who to speak to and the importance of the line manager relationship.

Client pressure

Making the next generation of lawyers – of which a higher proportion than ever before identify as disabled – comfortable in applying for the legal profession is important. Senior practitioners can also learn something from their juniors through reverse mentoring.

'Giving due consideration to disability in the workplace is about creating equity for all, but it is also becoming a business imperative for law firms'

Reena Parmar, Freshfields

Considering how individuals work to the best of their ability, whether through preference passports or an open conversation at the interview stage, builds more successful teams that ultimately produce the best work. Moreover, the current cohort which identifies as disabled will be heading not just to law but diverse business sectors, so law firm clients will also be weighing up how they can make similar accommodations.

And they could have the last word. The General Counsel for Diversity & Inclusion group already expects law firms to report on gender, ethnicity, LGBTQI+ and disability when reporting to current and prospective in-house clients. Social mobility data is also being added into the mix. ‘Clients want concrete examples that a law firm’s values align with their values, including data on disability inclusion,’ says Parmar. ‘Giving due consideration to disability in the workplace is about creating equity for all, but it is also becoming a business imperative for law firms.’

Katharine Freeland is a freelance journalist

For more information on the Law Society’s Disabled Solicitors Network click here

1 Reader's comment