A trawl of the Gazette’s archives to mark Black History Month yields some surprises for Eduardo Reyes

The low down

A journey through the Gazette’s archives for Black History Month makes for uncomfortable reading at times. Just as discomfiting are the gaps in coverage. Through decades, you would barely know from the yellowing pages of the magazine, and the pronouncements of Law Society luminaries and members, that the world outside was confronting issues of race. No Nelson Mandela or ‘Mangrove Nine’ trials. No Brixton Riot and Scarman Report. Then comes a shift. By the 1990s, Society presidents and committees are advocating for change and the result is uneven progress on race equality. They were responding to advocacy by networks such as the Society of Black Lawyers. But as she leaves office, the Society’s first Black president reflects that there is still much to do.

I open a copy of the Law Society Gazette from 1976, and the advertisement I encounter is jarring. Cancer charity The Marie Curie Memorial Foundation’s advert appeals for donations to meet its £2.5m annual running costs under the headline: ‘By all means – spread the news.’ But it is the picture the ad’s designer used to catch the reader’s eye that stops me dead. It is a grotesque caricature of a crouching Black African man using animal bones to beat the drum that covers his modesty. ‘Boom B B Boom Boom,’ goes the drum. His large hooped earrings fly about his head while a tiger emerges from grasses behind.

I am combing our archives because I am curious to set in context the legal landmarks and the firsts recounted and celebrated during Black History Month. I ‘trained’ as a historian and cleave to the notion that there is no text without context. I have pulled 1976 off the library shelf because it was the year the third race relations act received royal assent. I want to know how the profession was responding to a country and legal landscape that was changing rapidly.

The act merited no mention in the Gazette of November 1976, the month it received royal assent, or when it came into force in September the following year.

The first race relations act in 1965 merited a mention by the Law Society president Derek Hilton. He was not a fan. ‘Here there is a minority to be protected, albeit a very vocal minority,’ he said in his inaugural address. ‘So the act limits our right of free speech and moreover deprives each of us of the right to sell our house to the purchaser of our choice or employ the person of our choice.’

The Gazette did not at that time have the same mix of news and features it now does, but through the faithful reproduction of inaugural addresses, the letters page, its societies and activities listings, and its choice of which legal developments to cover, a picture emerges of a profession that was late to appreciate any sense of duty or role in furthering racial equality. Whether that be through the use of the law itself, or fair entry to and progression within the profession.

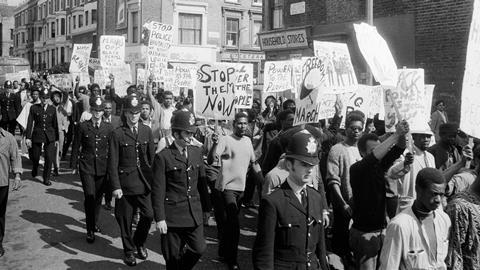

The 1971 trial of the ‘Mangrove Nine’, who were accused of inciting a riot, gripped the national media. The accused were charged after a protest at a police station against frequent raids on the Mangrove, a Notting Hill restaurant whose customers included Black writers and political activists. There were clashes between police and protesters at the demonstration.

After a 55-day trial the nine were acquitted of all major charges.

Two were litigants in person, one of whom was the writer and campaigner Darcus Howe.

At times the trial was of interest for its use of criminal procedure as well as trial theatre. Howe never qualified as a lawyer, but had studied at Middle Temple for two years and put his legal knowledge to use. Some 63 candidate jurors were rejected, and the nine used the case to challenge the legitimacy of the British legal process.

But in 1971 the Gazette was not gripped. The trial merited not one letter, note or report. The Gazette did, though, cover litigants in person in the context of a Justice report that concluded: ‘Litigants in person… are frequently unable to do justice to themselves and the cause for which they are fighting.’ A statement that was notably at odds with Howe’s electrifying acquittal.

In the 1960s, 70s and much of the 80s, the Law Society Squash Rackets Club received regular attention. Race did not, even as the law and society changed around Chancery Lane. A decade after the Mangrove Nine trial a report on the Brixton riots by eminent jurist Lord Scarman similarly received no coverage.

But this indifference to reporting and reflecting on issues of race changes by the start of the 1990s.

‘Only 1% of solicitors working in the City are Black’

At the start of Black History Month, the Law Society urges ‘action not words’. Society president I. Stephanie Boyce, its first Black president, says: ‘Black people often experience racism and discrimination. Then they are expected to fix it. This must change.’

The Society says it has been speaking to Black solicitors about their experiences of working in the profession. In 2020, it published its Race for Inclusion report, which shed new light on this issue ‘and indicated how we can build a more inclusive profession’.

Boyce continues: ‘Our research discovered the challenges and obstacles Black, Asian and minority ethnic solicitors face due to their ethnicity. Adverse discrimination was reported by 13% of Black, Asian and minority ethnic solicitors and 16% reported bullying.’

In the research a third of Black African and Caribbean solicitors said they have experienced some form of discrimination or bullying in the workplace – the highest figure reported by any ethnic group.

‘A lack of progression in larger firms was also an issue,’ Boyce says. ‘34% of partners in single-partner firms are from Black, Asian and minority ethnic backgrounds. As part of our report, we recommended that firms have open, honest conversations about race and what needs to change in their organisation, implement blind and contextualised recruitment, set targets for senior leaders, and instil a data-driven approach to diversity and inclusion.’

'I hope my work has gone some way to improving how the profession recruits and retains its talent. Personal characteristics or an individual’s socio-economic background should not determine how far people can go'

I. Stephanie Boyce, Law Society

The Society says that in the two years since it undertook this research, there have been signs of improvement. Its Annual Statistics Report 2021 found that representation of Black, Asian and minority ethnic solicitors continued to grow, reaching 18%. Black, Asian and minority ethnic solicitors working in private practice increased by 6%.

But, Boyce adds: ‘More work needs to be done in increasing representation of those from Black, Asian and minority ethnic, and low socio-economic backgrounds. Only 1% of solicitors working in the City are Black.’

To help firms develop and deliver a strategic approach to D&I, the Law Society recently launched its Diversity & Inclusion Framework.

The framework helps workplaces drive change by supplying a proactive three-step action plan that will help members develop and deliver a strategy that creates lasting change.

‘I hope,’ Boyce says, ‘the work I have done during my time as president has gone some way to improving how the profession recruits and retains its talent. Personal characteristics or an individual’s socio-economic background should not determine how far people can go.’

In September 1991 the Gazette story ‘Ethnic monitoring of judges’ posts ordered’ took a full page in the news section, following an announcement by the lord chief justice. ‘The [Law] Society, which has repeatedly highlighted what it sees as the defects of the present system of judicial appointments was quick to praise the move,’ the Gazette said.

It also quoted Peter Herbert, chair of the Society of Black Lawyers. Herbert welcomed the monitoring, which the SBL had called for in 1990. But nothing short of dismantling the entire system ‘which has discrimination built in’ would lead to more ethnic minorities and women on the bench, he added.

In October 1992, the Gazette noted: ‘Perceived or actual race discrimination within the legal profession is a hot issue. The official launch of the Law Society’s consultation paper detailing its equal opportunities proposals featured prominently in both the quality and popular press. All focused heavily on measures which would suggest to law firms that they aim to have a minimum number of ethnic minority fee-earners on staff.’

Also on the table was a draft practice rule outlawing discrimination and a ‘code of conduct’. A previous code of conduct, in place from 1988, was dismissed by a member of the Law Society’s race relations committee as ‘ineffectual’. Another member of the committee, Henry Hodge, noted that although ‘potentially a minefield, the proposals once explained to the profession, should be accepted by practitioners’.

What do we see that is shaping this closer focus on equality? How did it overtake the activities of the Law Society Squash Rackets Club?

Notably, what the rackets club had in the 1960s was a committee – a network that was recognised and attached to the representative body. Early women lawyers, academics writing for the Gazette have noted, emerged from networks, rather than being individual success stories.

By the early 1990s, the Law Society had its race relations committee. Its then secretary Jonathan Goldsmith, now a Gazette blogger and columnist, recalls: ‘At the time it was very novel – the first time that the Law Society had moved into the field of race relations and equal opportunity.’

The Society of Black Lawyers, and later the Black Solicitors Network, gave a platform and a voice for their members – and of course an all-important network. There has been, as BSN pointed out at its 25th anniversary, an acceptance in firms that equality and diversity make business sense.

But it is hard to avoid the conclusion that organising to promote equality has been key. It is what has entrenched standards and aspirations in the profession’s rules, secured media coverage and seen increased pressure on institutions and businesses to do better. This is also how the legal profession has acquired an improved language to address its challenges here.

By 1992 Law Society president Mark Sheldon’s inaugural address had a lengthy passage on gender and race equality. ‘We have come a long way,’ he said. ‘And two weeks ago the Law Society issued a consultation paper on proposed new measures concerned with discrimination on the grounds of race, sex or disability. It is not out of sentimentality that I believe it will be right now to adopt firm but tempered measures on the lines proposed.’

Sheldon added: ‘We will not succeed in maintaining and strengthening the united profession I wish to see if there is the continuing suspicion that unfair discrimination persists.’

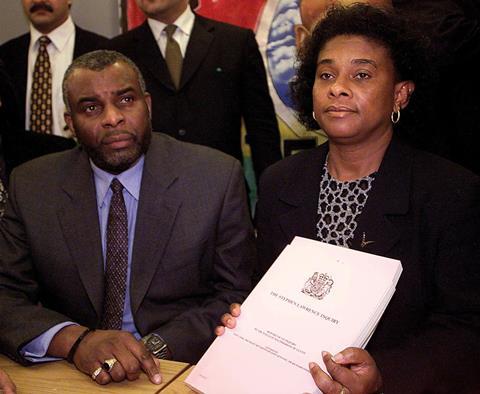

The Macpherson Report into the murder of Stephen Lawrence was, unlike the 1981 Scarman Report, heavily covered by the Gazette, as was the introduction of the public sector equality duty that followed. Stephen’s brother can now be found giving speeches at events run by international law firms.

'The Law Society [has] issued a consultation paper on proposed new measures concerned with discrimination on the grounds of race, sex or disability. It is not out of sentimentality that I believe it will be right now to adopt firm but tempered measures on the lines proposed'

Mark Sheldon, Law Society president, 1992 inaugural address

The Gazette’s archives also show how the ‘firsts’ accelerate from the 1990s. To pick a couple, lawyer Paul Boateng MP became the UK’s first Black cabinet member; Baroness Scotland added first woman and first Black attorney general to her long list of ‘firsts’. Taking office last year, I. Stephanie Boyce became the Law Society’s first Black president.

We have within living memory moved from a world where the trial of lawyer Nelson Mandela merited not one mention on Chancery Lane or in the Gazette to one where the South African president’s death saw the flags in the heart of legal London at half-mast. Tributes from legal figures flowed, many stressing that Mandela was a lawyer.

But as ever with history, race and the law is not a linear story of progress. As Boyce says: ‘A third of Black African and Caribbean solicitors say they have experienced some form of discrimination or bullying in the workplace – the highest figure reported by any ethnic group.’

Gazette readers will know that any story on equality and diversity attracts comments from readers who reject a focus on race, and who do not accept its relevance. After the murder of George Floyd, I interviewed the barrister Leslie Thomas KC, who recalled the disbelief of white colleagues when he related his experience of racism as a Black man. Commenters’ rebuttals to the case he set out included some which simply failed to accept the experiences of racism he related as a Black man.

Boyce is of course right to state that discrimination and bullying take place on grounds of race. But this is not 1965. The Law Society does not now have presidents who use their platform to denigrate legislation designed to ensure a Black lawyer can compete fairly for a job or a house. But it did not so very long ago, and we have a duty to look the awkward parts of our history squarely in the eye.

1 Reader's comment