In the second of two articles on disability in the legal profession, Katharine Freeland looks at the experiences of – and what must be done for – solicitors seeking to climb the career ladder

The low down

Many solicitors with disabilities feel pressured to conceal their disability.Some reach the top, but in doing so have not been visible role models. And lack of candour around disability means many do not progress their careers or drop out. There has been a failure to consider who the profession’s ‘design’ suits. However, an omerta around disability is increasingly being broken. The result is a dialogue addressing culture, reasonable adjustments and billable hours targets – all key for retaining and progressing the careers of disabled solicitors. Change is slow, but organised efforts – by the profession and some firms – are starting to make a difference.

Initiatives aimed at students have made significant inroads in encouraging disabled talent through the door of the legal profession, as outlined in the first Gazette article on disability and the law.

But once qualified, disabled lawyers must navigate promotion and partnership in a system dominated by two metrics: billing hours and winning clients. And they may not be getting the help they need. In 2020 the award-winning Legally Disabled report from the Law Society and Cardiff University found that many of those who took part feared negative consequences from sharing their disability. Even the most senior were reticent, concealing impairments even in cases of serious sight or hearing loss.

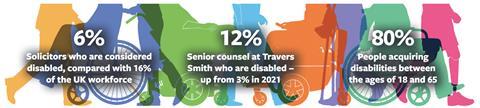

This view is compounded by other research. In 2021 figures from the SRA revealed that only 6% of lawyers were considered disabled, compared with 16% of the overall UK workforce. Speaking with law firms, as well as disabled associates and partners, and solicitors from in-house and a range of legal services businesses, the Gazette examines the position today and explores how disabled lawyers can be better equipped to reach their full career potential.

Diverse teams

Many will be familiar with McKinsey’s findings that diverse teams are the most successful, capable of challenging the consensus and bringing different life experiences to the table. Although diversity is often seen by diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI) teams primarily through the prism of race and gender, it should also include disability.

This is not just the humane approach but it makes business sense: updated research from Accenture and Disability:IN, The disability inclusive imperative, shows that companies that lead in disability inclusion drive more revenue, net income and profit. Disabled employees are also 25% more likely to outperform on productivity compared with their industry peers, measured by revenue per employee.

These statistics come as no surprise to disabled lawyers such as Jonathan Fogerty, an associate from north-west serious injury firm CFG Law. Tetraplegic since a diving accident at 14, Jonathan now helps support people after serious and catastrophic events such as spinal cord injuries.

‘Since a young age I have been a manager,’ he says. ‘I have supervised two carers and handled troubleshooting if things go wrong. Disabled people have to be excellent planners to carry out tasks that others would not think twice about – getting up and going to work every day, or catching a train. This experience and depth of perspective is a strong asset to my performance as an employee.’

Throughout his career, Fogerty has spelled out to employers what he needs so that he can flourish and obtain the best results for clients. This open, continuous communication is crucial – creating an environment where disabled people feel comfortable enough to convey their requirements at every stage.

The question of how to make workplaces more inclusive for those with disabilities affects everyone. With 80% of people acquiring disabilities between the ages of 18 and 65, according to a report by Accenture, many people find themselves needing to request reasonable adjustments at work, the reasons for which might be hidden from employers.

Lack of partner-level role models

Role modelling is essential to illuminating the path for others. In 2020, Legally Disabled noted that senior disabled people tend to leave the profession prematurely or feel pressured to ‘step down’ from senior roles. The research also highlighted the importance of disabled people in senior roles feeling comfortable enough to share their identity.

‘If your law firm doesn’t have any disabled partners, you must ask yourself why,’ says Chris Seel, diversity and inclusion adviser at the Law Society. ‘It may be the case that they are uncomfortable speaking out as they feel your culture is not sufficiently inclusive and that they may be discriminated against.’

The number of partners from some City firms sharing the fact that they are disabled has risen in recent surveys, although this is not representative. For example, at Travers Smith – which has no billable hours targets – disabled partners now account for 10% of the partnership, compared with 8% in 2021, while the percentage of disabled senior counsel stands at 12%, a jump from 3% in 2021. Despite these encouraging signs, partners willing to talk openly about the challenges of their path to partnership are hard to find.

'Telling personal stories is important if progress on disability inclusion is to be made. When I spoke out about my experience, I was overwhelmed by the support that I received'

Mark Blois, Browne Jacobson

‘There is a double penalty in expecting people who are already dealing with barriers and prejudice to also spend time role modelling, and improving diversity and inclusion in a firm, and then measuring their performance (for example, billable hours) the same as everyone else,’ says Seel. Whatever the cause, the lack of disabled role models in partnership and management is unhelpful for those who follow.

‘People worry about sharing information that shows a vulnerability, especially in a traditional service culture such as the law,’ says Mark Blois, a partner and national head of the education team at national firm Browne Jacobson. ‘But telling personal stories is important if progress on disability inclusion is to be made. When I spoke out about my experience, I was overwhelmed by the support that I received.’

Recognised by the ‘Disability Power 100’ as one of 100 people disabled or living with an impairment who, through their example, inspires others to achieve their full potential, Blois talks about his personal path to partner and team head with cystic fibrosis.

‘When I started out, I thought that it might be too difficult to work in a law firm environment full-time,’ he says. ‘But I was fortunate enough to be supported by key individuals at the firm who were encouraging and open to being adaptable. This allowed me to pursue my career and climb the ladder.’

Blois makes the crucial point that support from line managers or supervisors is critical to enabling lawyers with disabilities to succeed, but this must be underpinned by a platform of systemic support. ‘The trajectory and success of your career should not be a matter of “luck” – dependent on who your supervisor or line manager is,’ he says.

To effect systemic support throughout a firm, disability awareness should underpin all internal policies and procedures, with those relating to retention, exit and promotion in particular under regular review. While the pandemic opened up a new world of flexible working, it is important that firms differentiate between the right to request flexible working or parental leave and disability leave in its own right – which allows people the space to take time out, for medical appointments, for example, without cutting into other rights.

Getting started: easy wins

The Law Society’s Disabled Solicitors Network sets out some ‘easy wins’, based on the Legally Disabled research.

- Review and examine the reasonable workplace adjustments policy. Monitor requests for adjustments while implementing change. An increase in requests should be viewed as positive and evidence that people are more confident to self-identify as disabled.

- Review other key policies with disabled people in mind. Does your firm have separate sickness absence, occupational health, training, performance management and flexible working policies?

- Include in all recruitment and appraisal processes the question: what adjustments would help you realise your full potential? Ensure recruitment staff and appraisers know how to respond to the answer or can take it away and get back to the interviewee or appraisee.

- Make staff aware of the EHRC guidance on commonly accepted reasonable adjustments.

- Ensure there is a disability leave policy to sit alongside similar policies such as parental leave.

- Is there a staff network run by disabled people in the organisation? If not, encourage people to set one up. Provide support and allow them time to do this work. Representatives from across the organisation should be involved so as to properly appreciate and address concerns.

- Introduce a dedicated and trained disability officer as a point of contact to discuss adjustments and ensure they are visible to potential applicants, clients, employees and line managers.

- Does the firm website provide sufficient information about accessibility and reasonable adjustments available to visitors and staff? Could you put maps, plans and photographs on the site or send to applicants and visitors? As well as helping those with physical accessibility requirements, this helps to relieve anxiety for everyone.

- Introduce a ‘disability passport’ scheme. This records agreed adjustments and can accompany an employee throughout their journey in an organisation addressing the widely reported problem of disabled staff having to share multiple times to different personnel. This scheme could be extended to the whole organisation, to avoid singling out disabled employees.

- With technology and software, consider turning on all accessibility features; and require a business reason for turning any off.

For more information, click here.

Nuanced approach to promotion

Promotion pathways should be carefully scrutinised for discriminatory assumptions. ‘We seek to forge a route to partnership that is diversified, taking account of different personalities and management styles,’ says Charlotte Yirrell, senior diversity and inclusion manager for the UK, US and EMEA at Herbert Smith Freehills. The firm is, along with 20 other firms including Hogan Lovells, Ashurst and Addleshaw Goddard, one of the Valuable 500 – 500 CEOs and their businesses which have signed up to putting disability inclusion on the leadership agenda.

Measurements to decide who to promote will always involve a tension between qualitative and quantitative feedback, but the more tailored the approach the better. With core metrics such as sickness reporting, disciplinary and performance regularly used as indicators for promotion, 56% of solicitors and paralegals surveyed by Legally Disabled believed that their career and promotion prospects had suffered. Danielle Gleicher-Bates, co-founder and co-chair of Neurodiversikey, a non-profit organisation focused on fostering neuroinclusivity in the law, says: ‘Neuronormative ideas of professionalism, ability and success permeate assessment criteria, putting neurodivergent individuals at a disadvantage by default.’

Legally Disabled also pinpointed an issue with the use by HR teams of external recruitment agencies, which can fail to offer reasonable adjustments to disabled candidates or are believed to be screening them out. Under Equality and Human Rights Commission guidance, there can be no displacement of responsibility: law firms should ensure that external providers receive disability awareness training and undergo disability equality audits. ‘Regardless of the ethical reasons for ensuring that external recruitment agencies offer equal access to disabled candidates, legally, anything done by an agent for a principal is treated as having also been done by the principal. This is the case even if the principal did not sanction or have knowledge of the discriminatory behaviour,’ says Penny Morrison, senior associate at employment boutique Osborne & Wise.

Management buy-in

Disability is not solely an HR issue and nor should it be, with Legally Disabled finding that many disabled lawyers feel that HR is too aligned to the interests of the firm to assist them. An open dialogue between HR, the DEI team or representative, and senior management on initiatives to promote disability inclusion can reap benefits.

Appointing a ‘disability champion’ to argue for the allocation of resources, or forming a disabled affinity group, not only provides mentorship and a sense of community but can also be a powerful conduit to management, so long as initiatives do not take place in a silo. Reverse mentoring schemes, where a disabled junior mentors a partner, are also a highly successful tool for creating understanding and forcing change. Other schemes such as passporting, reducing the need to explain an individual’s needs to different line managers, can also be useful – if framed sensitively. Data is also vital to monitor progress and identify lacunae, with disability pay gap surveys providing valuable insights.

Work in progress

The sheer scope of disability, ranging from neurodivergent conditions such as ADHD and autism, to severe physical impairments, is a huge challenge for law firms. Helpful resources can be found at City Disabilities (citydisabilities.org.uk) or through the Law Society. A fundamental building block of inclusion is taking an individual approach rather than focusing on blanket policies.

‘Asking the question “tell us what you need?” at regular reviews, not just at the entry point, actually benefits everyone in the workplace as it normalises discussions about the support and tools that individuals need to thrive,’ says Reena Parmar, chair of the Law Society’s Disabled Solicitors Network and is counsel in global transactions at Freshfields Bruckhaus Deringer.

Checking in with every employee can tease out unseen needs; the able-bodied associate with a disabled child, or the person newly diagnosed with ADHD who requires a quiet room in which to work. Without such attention disabled talent can be forced out of private practice.

Traditional law firms, especially in the City, are known for an expectation of service on demand and the billable hours culture, despite the latter failing to reflect the quality of any client relationship.

'It is disability, not inability – we need to remember that'

Dame Fiona Woolf

While some disabled lawyers feel supported and that their needs are met, others have been burned by the exhortation to ‘bring your whole self to work’, with their requests for reasonable adjustments receiving a lacklustre reception from unsympathetic managers.

‘It is disability, not inability – we need to remember that,’ says Dame Fiona Woolf, former energy partner at CMS Cameron McKenna and former Law Society president. ‘But until law firms give lawyers more credit for developing all talent and investing time in other people’s career progression, rather than evaluating success through billable targets, everyone will be at a disadvantage, especially disabled people. We must let all talent rise.’

Big Law may appear to present an attractive culture of inclusion (and remuneration) for the disabled lawyer, but there are alternatives for a fulfilling career – in-house and a full spectrum of legal services businesses such as ALSPs and virtual law firms, many of which have no billable hours targets. Offering equally fulfilling promotion structures to the traditional partnership model may help retain disabled people and give them the opportunity to progress more effectively.

‘Current expectations and modes of career development and progression can be part of the problem,’ says Charlotte Clewes-Boyne, co-founder of Neurodiversikey. ‘For example, in law firms, partnership may not be desirable for some neurodivergent lawyers, but they may still wish to progress and feel that they are doing valuable work.’

‘As a person with a disability, you must have an honest conversation with yourself about how to manage the demands of the job. Work out which practice area and firm set-up will work best for you, and bear in mind that being successful takes stamina and resilience,’ says Fogerty, who has managed to shape his legal career to fit his needs. This included negotiating a four-day week in the 1990s when such arrangements were uncommon. ‘If you want to be a partner, can you manage the extra responsibility and time needed for networking and personal brand-building that this will take? Sometimes, focusing on achieving the best outcomes for clients, rather than goals such as partnership, can be the most satisfying reward.’

Katharine Freeland is a freelance journalist

No comments yet