When governments and companies flout their climate commitments, can the courts hold them to account in good time? Joanna Goodman reports on the hopes invested in environmental litigation

The low down

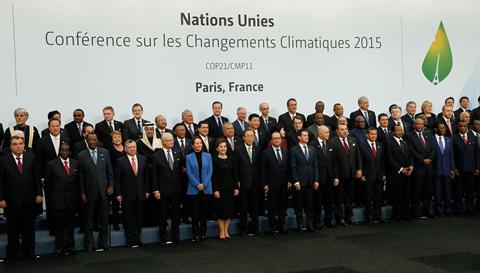

When the Paris Agreement endorsed the United Nations target of keeping global warming to no more than 1.5C above pre industrial temperatures, it was met with jubilation and relief. But as the UK government’s U-turn on key environmental targets, announced in September, shows, the follow-up actions required to achieve that target have been woefully inadequate. There is increasing recourse to litigation in attempts to force compliance by governments and businesses to meet their commitments. Climate change cases have doubled since 2017. But despite notable successes, governments retain wide discretion in decision-making and seem willing to use delaying tactics. In the context of the climate emergency, do we have time to rely on the courts? Lawyers taking such cases argue we don’t have a choice.

Climate litigation is increasing exponentially. According to the UN Global Climate Litigation Report 2023, the number of climate change cases has more than doubled since 2017. London School of Economics (LSE) research report Global trends in climate change litigation: 2023 snapshot found 2,341 cases in the Sabin Center for Climate Change Law climate change litigation databases; 190 of those were filed in the 12 months to May 2023. And their range and impact is expanding. More than 50% of climate cases have direct judicial outcomes in terms of climate action. Others have indirect outcomes beyond their specific remit.

A strategic tool

Climate litigation is a strategic tool. The LSE reports highlights eight categories:

- Government: 81 cases against governments, challenging their overall climate policy response, including failure to implement policies.

- Corporate: 17 cases against large corporations, challenging their climate plans, targets and claims (greenwashing).

- Project related: 206 cases against specific decisions, policies and projects – e.g. new fossil fuel projects.

- Funding related: 28 cases preventing funding of harmful projects and activities, including public bodies and 12 against private parties including banks and pension funds.

- Failure to adopt: 14 failure to adopt cases against governments or corporations.

- Polluter pays: 17 cases seeking compensation for alleged climate change harms.

- Climate washing: 57 cases challenging inaccurate claims – 52 against corporations.

- Personal responsibility: eight cases seeking to attribute personal responsibility for failure to manage climate risks.

An additional category is downstream litigation, which contends that large corporates are responsible for the environmental damage caused by the use and disposal of their products.

‘Most of the cases are drawn from human rights law, public and regulatory law, and, more recently, [as in the High Court case against Shell] company law,’ says Hausfeld partner Ingrid Gubbay.

Not all climate cases are successful, but they are drawing lines in the sand when it comes to climate responsibility and government policy. The Australian government recently settled a lawsuit brought by law student Katta O’Donnell, claiming that it had breached its legal duty by not informing current and future investors in government bonds of the financial risk associated with the impact of climate change. It agreed to publish a statement on the Treasury website acknowledging this.

However, the High Court of England and Wales maintained its decision to reject ClientEarth’s landmark lawsuit against Shell’s board of directors. ‘Our derivative claim is the first worldwide to argue that corporate directors should be held personally liable for their failure to prepare for the energy transition,’ says ClientEarth senior lawyer Paul Benson. ‘We are disappointed by the court’s decision, but this is a cutting-edge case on important points of law. The court has accepted that climate change poses significant and foreseeable risks to Shell. We firmly stand behind our claim that the board is currently neglecting to address those risks adequately, to the detriment of its shareholders.’

Time is running out

But time is running out. As Matthew Gingell, general counsel at Oxygen House, who is also the founder and chair of the Chancery Lane Project, says: ‘Climate litigation is a fantastic tool for raising awareness and holding government and business to account. However, litigation takes too long. It took 782 days to bring the Friends of the Earth versus Shell case through the Dutch courts, and that’s now in appeal. And it took 685 days to enact the Environment Bill. The problem is we have finite laws, courts and funds.’

While the Paris Agreement pulled together the long-term quantitative goals, including the aspirational goal of limiting global warming to 1.5C by 2050, ‘it is not enforceable and each state has autonomy over their Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs), so accountability fell to domestic jurisdictions and it has now percolated to regional and international courts,’ Gubbay explains. Parties to the Paris Agreement reaffirmed the 1.5C commitment at COP26 in Glasgow and COP27 in Sharm El-Sheikh.

Climate litigation has heightened awareness among companies. ‘In July the government signed up to the task force on Climate disclosure, the last phase of which will require companies to measure and publish their emissions,’ says Gubbay.

Even on the domestic front, the growing number of cases and the time it takes to get them through the courts is delaying progress. Associate solicitor Carol Day, who founded Leigh Day’s environmental litigation service in 2013, explains: ‘We’ve been involved in quite a few challenges, including for Friends of the Earth, and site-specific cases, including the Supreme Court challenge to the planning application for oil and gas drilling in Surrey.’ The latter is the only case at the moment which looks at downstream emissions – the emissions from burning the product elsewhere. Therefore, she says: ‘The outcome has implications for other proposals.’

The number of cases is a challenge for the judiciary, in terms of both time and expertise. ‘A wider set of judges are grappling with these issues,’ says Day.

Another issue is the time it takes to get information from government departments and local authorities. ‘We are seeing that more and more with standard requests for information that should be answered in 20 days,’ Day explains. ‘Government departments routinely request extensions, which compresses our ability to work on the cases. Most planning decisions have a six-week deadline, and judicial review cases can take up to three months. But a 20-day delay to an infrastructure project challenge is quite significant. Once you’re into the litigation it’s different, but we are seeing a push back on candour at the pre-action protocol stage.’

Climate conscious lawyering

The rise in climate litigation and awareness of its inherent risks have provided more work for environmental lawyers. Nine out of 10 of the world’s top law firms have published reports on climate litigation, and professional bodies have issued guidance on key risks, including the potential of litigation against law firms in the context of net zero.

The Law Society Guidance on the impact of climate change on solicitors covers how law firms advise their clients and the duty to understand and manage risk. But while the guidance operates in conjunction with the Solicitors Regulation Authority Principles, it is voluntary, and the SRA is still considering the regulatory position. ‘The legal sector isn’t being pushed by regulation’, explains Law Society policy adviser Alasdair Cameron. The IBA Climate Crisis Statement, ratified in May 2020, urges lawyers to take a climate-conscious approach to problems encountered in daily legal practice and to advise clients of the potential risks, liability and reputational damage arising from activity that negatively contributes to the climate crisis.

Lawyers are helping client organisations towards net zero targets and with reporting obligations. The Chancery Lane Project has produced open access clauses covering common climate obligations. Becky Annison, head of engagement, explains. ‘More firms are integrating climate contracting into their work. That is, the use of contractual clauses in legal documents that mandate decarbonisation targets to deliver net zero goals. Our 2023 impact survey found that 58% of respondents have used some form of climate provision in their contracts and/or legal documentation. Of these users, nearly half (48%) are actively monitoring compliance and 70% have some form of breach mechanism in place. Increasingly, corporations are recognising the risks that climate change pose to their businesses and that making voluntary obligations into contractual ones is an effective and relatively easy way to reduce these risks.’

Human rights

Nina Pindham at Cornerstone Barristers represented Friends of the Earth in their successful challenge to the government’s net zero strategy. ‘While the European Court of Human Rights [ECtHR] has not yet decided a case on climate change, national courts in Europe have, including the landmark Dutch Supreme Court in Urgenda Foundation v The Netherlands. This found that the risks caused by climate change are real and imminent, and present significant threats to the rights guaranteed by the European Convention on Human Rights [ECHR].’

Pindham highlights three pending ECtHR cases against states. She says that states’ human rights obligations include reasonable and proportionate measures to safeguard against the threat of climate change. Failure to do so is in breach of Articles 2 (right to life) and 8 (right to family life) of the ECHR. The outcomes of these cases have ramifications across the EU and signatories to the ECHR.

Verein KlimaSeniorinnen Schweiz v Switzerland is a case brought by a group of older women and young people concerned with the consequences of global warming on their living conditions and health. They allege that Switzerland has failed to fulfil its obligations under articles 2 and 8 of ECHR, in the light of the principles of precaution and intergenerational fairness contained in international environmental law.

'At a minimum, states should put in place laws, structures, policies and programmes that align with the commitments made in the Paris Agreement'

Nina Pindham, Cornerstone Barristers

Carême v France is a complaint by a former mayor that France has taken insufficient steps to prevent climate change.

Agostinho v Portugal and 32 Other States concerns greenhouse gas emissions from 33 member states, which a group of Portuguese nationals aged between 10 and 23 allege contribute to global warming, affecting their living conditions and health.

Pindham says these cases ‘argue that, while climate change is a global problem, human rights law – interpreted against the background of international climate change law – requires states to do their part, on the basis of common but differentiated responsibilities’, in line with the precautionary principle. ‘At a minimum, this means putting in place laws, structures, policies and programmes that align with the commitments made in the Paris Agreement,’ she adds.

Challenging government

While most of the leading cases are based on combining the Paris Agreement with the ECHR, the UK has not formally implemented the Paris Agreement, although it is a signatory. ‘Most of the leading challenges are judicial review, where the government has a broad discretion,’ explains Gubbay. ‘So even though the UK has legislation in the climate Change Act 2008, and we were leading in this area, the act has only played a small part in recent cases.’

Rowan Smith at Leigh Day represented Friends of the Earth in its successful Net Zero Strategy challenge. ‘Last year, the High Court concluded that the government’s Net Zero Strategy was unlawful and breached section 13 of the Climate Change Act 2008 which requires the government to have policies that will meet the carbon budgets,’ he says. ‘In reaching that conclusion, the court found that the government had failed to fully consider the quantified contributions those policies would make to reducing carbon emissions, over what timescale they would be implemented and the degree to which there was a risk to them being delivered. The court ordered the government to address those flaws in a new strategy.’

This sits uneasily with prime minister Rishi Sunak’s 20 September U-turn on climate commitments. Smith says: ‘The current judicial review challenges that new strategy [the carbon budget delivery plan] on the basis that the government still hasn’t fully taken into account the risk to delivery. There is also a supplementary argument that the government has breached the requirement for the policies to contribute to sustainable development, because it has admitted that those policies fall short of its Nationally Determined Contribution to meeting obligations under the Paris Agreement.’

‘Judicial reviews are a critical legal tool to hold the government accountable when it takes decisions on the environment or on climate which are potentially unlawful,’ says Benson. ‘Take the recent approval of the Rosebank oil field in the North Sea and the prime minister’s roll back of net zero policies. These decisions are bad economically and bad for the public, because they are the essence of short-termism. But they are also legally risky. Judicial review allows for them to be scrutinised in a court of law – and potentially overturned.’

He continues: ‘ClientEarth is already challenging the government’s existing climate plan on the basis that its policies cannot be relied on to deliver the UK’s carbon budgets, in line with the Climate Change Act. This is the second time we have taken the government to court in under two years. The first time, we won – and so the government had to strengthen its plans. But the revised action plan still falls short, and so we are going back to the High Court.’

Competition law

Not all climate litigation is based on human rights or corporate law. In August, Leigh Day, representing environmental and water consultant professor Carolyn Roberts, issued the first of six environmental collective action claims issued against Severn Trent Water on behalf of millions of customers allegedly overcharged by water companies. Roberts contends that if water companies had correctly reported pollution incidents, performance penalties would have been applied, reducing customers’ bills. This is the first collective action case where the alleged competition abuse centres on compliance with environmental laws and reporting responsibilities to regulators. Further claims will be issued against Thames Water, United Utilities, Anglian Water, Yorkshire Water and Northumbrian Water. Severn Trent ‘strongly refute’ the claim. Industry body UK Water has said claims against the companies are ‘entirely without merit’.

Leigh Day has pioneered large group environmental litigation actions in UK courts and has obtained substantial compensation on behalf of victims. International work includes representing communities who live along the Niger Delta who allege that their way of life has been devastated by oil spills.

Greenwashing

‘Many law firms are making climate-related commitments themselves, or advising clients who have done so, and many lawyers are advising on climate-related regulations and the implications of climate change for existing laws,’ observes Benson. ‘Advised emissions are perhaps the most significant source of climate impact for lawyers – and law firms may face regulatory and reputational consequences if their sustainability claims can’t be backed up and are perceived as greenwashing. ‘Like any other business, law firms that make net zero claims should think carefully about whether their work and business practices are compatible with those claims.’

Alasdair Cameron, policy adviser, climate change, planning and environmental law at the Law Society, highlights the litigation risk against law firms in the context of net zero. ‘The Law Society guidance on the impact of climate change on solicitors covers how law firms advise their clients, their duties to understand risks and flag them up. The SRA, too, is looking at climate change,’ he says. ‘While the solicitors code of conduct doesn’t talk about greenwashing, law firms need to scrutinise their own statements. The Competition and Markets Authority is increasingly looking at this.’

Although litigation can feel frustratingly slow, especially as important targets approach, it is making a difference on multiple fronts. ‘Certainly litigation can be complex and it can be slow, which can seem at odds with the urgency of the crisis,’ says Benson. ‘That said, new positive legal precedents can significantly help to move the dial. What we’re seeing from the swell of climate litigation is that the variety of legal avenues being used and the diversity of claimants bringing cases is growing at pace. In the last few years alone, we have seen action against companies under consumer protection, tort and company law. Climate litigation is here to stay, and companies will increasingly have to manage that risk.’

Joanna Goodman is a freelance journalist

No comments yet