How have courts, lawyers and parties adapted to the digital revolution unleashed by the pandemic? Catherine Baksi reports

The low down

In March 2020 courts rapidly moved online. The three Covid lockdowns accelerated HM Courts & Tribunals Service’s existing digital plans, with the roll-out of the Cloud Video Platform in July 2020. Since then remote hearings have become part of the legal landscape. But feedback has been mixed, depending on the type of court, case and client. There are particular concerns surrounding crime and family cases. Yet the widespread use of remote hearings is clearly here to stay. How can they be used to ensure that they deliver justice and what should be their limits? Could there ever be a fully remote jury trial?

Necessity is the mother of invention. Ministers had been trying to increase the use of technology in courts for years. Then almost overnight, the pandemic resulted in a radical and swift transition to the widespread use of remote hearings across courts, enabling them to take place without all participants being present.

As Law Society president Lubna Shuja says, remote hearings were an ‘invaluable tool in keeping the justice system operating’.

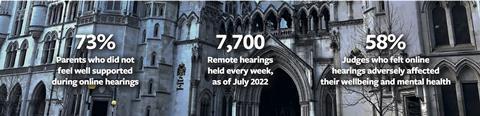

But, with the worst of the pandemic hopefully over, remote hearings look set to remain a feature of the justice system. According to the latest figures from the Ministry of Justice, as of 11 July this year, over 7,700 remote hearings were taking place each week – 32% of all non-paper hearings.

The lord chief justice, Lord Burnett of Maldon, gave guidance to judges in February on how to determine which hearings it is appropriate to conduct with some or all parties attending remotely.

He said it was ‘not a prescriptive practice direction’ but intended to assist in promoting consistency and predictability in the Crown courts. Accordingly, a variety of protocols has been issued by resident judges to suit local conditions and circumstances.

Lord Burnett said: ‘The decision as to whether participants attend a hearing remotely or in person is a judicial decision and a matter for the discretion of the judge in each case applying the “interests of justice” test in the light of all the circumstances.’

In general, he said that any hearing in which a witness is to give evidence, whether in person or remotely, will normally require the advocates to be present in court, as will all hearings where a defendant is required to attend in person. All hearings where the defendant attends remotely will require defence advocates to be able to communicate confidentially with their client immediately before and after the hearing.

Hearings generally suitable to be conducted remotely include mentions, bail applications, ground rules hearings, custody time limit extensions, uncontested Proceeds of Crime Act hearings and others involving legal argument only. Sentencing hearings ‘will require consideration on a case-by-case basis’.

Giving evidence to the Commons justice committee last month, Lord Burnett said that in the Court of Appeal Criminal Division, ‘almost all of the appellants’ and ‘lots of advocates’ attend remotely.

In the Crown and magistrates’ courts, he said, lawyers and others attend many preliminary and routine hearings remotely, adding that even in trials, witnesses, defendants and advocates have attended remotely. He said: ‘Most advocates are not very keen to have their witnesses give evidence remotely because there is a lack of immediacy and a lack of engagement with the jury or the decision-maker, but nonetheless it can happen.’

Burnett told MPs: ‘It is not suitable for everything, but I think the use of technology is as widespread as it should be.’ He added that ‘it can be really advantageous, particularly to make life easier for those attending’, but cautioned that ‘it is a mistake to think that it necessarily speeds things up’.

While the technology to enable the Cloud Video Platform, through which remote attendance is facilitated, is ‘pretty good’, Lord Burnett said ‘it is not perfect’. He gave an example of a recent Court of Appeal Criminal Division case he had been hearing when the bench had to stop to sort out a technical problem. ‘That, I am afraid, is a feature of using remote technology,’ he said.

To ‘step up on what we are using at the moment’ and improve reliability, he said, HM Courts & Tribunals Service has been developing a bespoke ‘video hearing system’. This has been piloted in a number of jurisdictions, but has ‘run into some technical difficulties and so it is a little stalled at the moment’.

Lawyers say the use of remote hearings depends on the attitude of the bench, with some judges more averse to it than others.

Loss of respect – and connection

Recently, a virtual hearing was interrupted by the sound of a couple having sex, prompting one senior judge to clamp down on the use of remote hearings. Jeremy Richardson KC, the honorary recorder of Sheffield, adjourned a hearing in which it transpired that one of the advocates attending remotely had been simultaneously watching pornography.

Last year, a case concerning Swindon Town FC, heard virtually before the High Court, was interrupted by online observers. The Swindon Advertiser reported that members of the public blew raspberries, swore at the judge and shared obscene images.

This year, the tribunal chairwoman hearing the case brought by barrister Allison Bailey against the campaign group Stonewall and Garden Court Chambers, had to warn viewers not to sign in using offensive names, which could be seen by others.

A report in April showed that three-quarters of magistrates were not in favour of using remote hearing links as often as they had during the pandemic.

Carried out by the Magistrates’ Association, with the legal charity Transform Justice, the study canvassed 865 magistrates and concluded that audio and video links negatively affected communication and participation, particularly for vulnerable court users.

One respondent said: ‘I doubt that I have ever had a day’s sitting without at least two or three breaks due to technical problems.’ Another noted that some defendants appearing remotely ‘had a complete lack of respect for the court, staff and process, including but not limited to: appearing while in the bath, being half-naked, smoking and treating the process like social media’.

An 2020 survey of around 300 court users by Transform Justice found that 58% thought appearing on video made it more difficult for defendants to understand what was going on and to participate.

Meanwhile, research published by the MoJ last December revealed that 58% of judges and 54% of lawyers felt their health and wellbeing were negatively affected by online hearings. It showed that judges felt more pressured and tired, magistrates felt less confident about decision-making when the legal adviser was not in the same room, and lawyers working from home found managing boundaries between work and home harder.

This followed Law Society research from 2020 that found that only 16% of solicitors felt vulnerable clients were able to participate effectively in remote hearings, and just 45% were confident that non-vulnerable clients could do so.

Video guides for lay users

Despite the expanding use of remote hearings, there is very little online support to prepare the public for appearing from their own home or to guide them around these new virtual spaces.

This led to concerns about access to justice and due process, in particular the ability of the disadvantaged to interact with the legal system in this way.

Working in partnership with HM Courts & Tribunals Service, the Supporting Online Justice project, led by Linda Mulcahy and Anna Tsalapatanis from the Centre for Socio-Legal Studies, and Emma Rowden from the School of Architecture, Oxford Brookes University, set out to produce a series of video guides for lay users for use in tribunals and family courts.

The project drew on extensive consultation with the public, court and tribunal staff, interest groups, practitioners and policymakers. It was helped by an advisory group chaired by Sir Ernest Ryder, the former senior president of tribunals and now master of Pembroke College, Oxford.

During the design of the films, the research team was guided by five key goals: enhancing technical competence; improving understanding of court processes; supporting court users in navigating the virtual space; engendering a sense of journeys to and from civic space; and promoting dignity and gravitas in virtual court proceedings.

They developed five films to help lay users of the justice system access and participate in online hearings. These include a generic film designed to be useful across a range of courts and tribunals, along with jurisdiction-specific films for: the Special Educational Needs and Disability Tribunal; the Social Security and Child Support Tribunal; the Employment Tribunal (England and Wales/ Scotland); and the Family Court (Private). They are available with subtitles in six languages along with a British Sign Language version for each one.

All films can be viewed on the HMCTS YouTube Page.

Online limits

Two years on, Shuja reports that solicitors consider remote hearings to be ‘working well in more technical administrative proceedings, cases in the commercial courts and in hearings which only involve judges and advocates’. But she says they are ‘working less well for cases which involve live evidence or significant disputes, such as contested family hearings’.

While hearings involving vulnerable parties should usually be heard in person, Shuja suggests that some, including those involving victims of sexual offences and those with disabilities which make getting to court difficult, can benefit from them being done remotely.

In July 2021, the Nuffield Family Justice Observatory published its third report into how the family courts were dealing with remote hearings. Initiated by the president of the Family Division, if found that nearly two-thirds of the professionals who responded felt that more needed to be done to ensure that they were fair and worked smoothly.

There was support for remote ‘administrative’ hearings but much less for remote fact-finding hearings, hearings involving contested applications for interim care or contact orders, or final hearings.

Most parents (73%) indicated that they did not feel supported during hearings. Nearly half (46%) did not have legal representation, and others raised concerns about not being able to be with their legal representative during the hearing.

While many professionals reported that the technology to support remote hearings had improved, responses indicated a high proportion of hearings still taking place by phone, and issues with connectivity and access to appropriate hardware.

One in three parents who responded had joined a hearing by phone, even if the hearing was by video conference. There were also continuing problems managing remote hearings where intermediaries or interpreters were required.

Remote hearings work best, says Juliet Harvey, the national chair of family lawyers group Resolution, when no live evidence is due to be given. She would welcome greater consistency among judges. ‘Different practice is adopted from court to court – and in some instances from judge to judge within the same court,’ she says.

She also complains that ‘cases still change at short notice from attended to remote and vice versa’, which is ‘a real pain’ for lawyers and litigants. Harvey suggests that parties could indicate why cases should be heard remotely, for example if there are childcare, accessibility or medical issues.

Increased coverage

Despite the difficulties, Edward Jones, vice president of the London Criminal Courts Solicitors’ Association, says most members welcome remote hearings. They allow solicitors to cover more hearings, at court centres around the country, on the same day, which for junior criminal and other legal aid barristers, means they can earn more money. Significantly, this helps all courts tackle case backlogs.

But, warns Ellen Lefley, a lawyer at the law reform group Justice, it can mean that junior lawyers miss out on informal learning opportunities, such as conversations with colleagues at court.

And Harvey suggests that remote hearings can take more time and resourcing than attended hearings. Each case is given a defined time slot, she explains, and if one runs short or is vacated, the next cannot be brought on, as would happen where parties were present in court.

Jones would like to see virtual hearings made the default option for certain types of hearing, rather than having to make a request to the court, but feels that is unlikely to happen. On the whole, he says that judges and magistrates are ‘generally reasonable’ when making decisions. But, like Harvey, he would welcome firmer guidance, especially in the Crown court, where he says ‘some judges are intrinsically hostile to remote hearings’.

Lefley stresses that the client’s needs and wishes must be central to the decision about the mode of hearings. ‘Some people need in-person support or to be in a room to understand proceedings,’ she insists: for example, those who need an interpreter or intermediary and some people with neurodivergence.

She stresses that others ‘are digitally excluded, without the technology, skills or confidence for online justice,’ adding that in ‘traumatic, personal or otherwise sensitive cases, the dignity of the proceedings is difficult to achieve online’.

Lefley also highlights the experience of unrepresented parties, for whom the ‘already alien court process’ may have become another ‘way to experience a frustrating, alienating and marginalising court process’.

Seen to be done

Remote hearings have the potential to make watching cases more accessible for the public and press, but there is concern that journalists are sometimes wrongly excluded.

Because the pandemic accelerated the use of technology ‘ahead of time’ and ‘not as a result of careful testing’, Lefley is also concerned that remote hearings can affect outcomes. Evaluation, she insists, is essential, including research into the value of in-person witness evidence and the appraisal of demeanour. ‘Without it, we are making changes in the dark rather than responding to evidence,’ she says.

In 2020, Justice evaluated a mock virtual jury trial, which found that juror engagement was improved. In the online trials, the defendant was literally and metaphorically at the centre of the proceedings, which could be perceived as more democratic than face-to-face trials.

'A trial is real life and not watching a television drama…remote hearings can distort and remove the gravity of the situation'

Kirsty Brimelow KC, Criminal Bar Association

But Kirsty Brimelow KC, chair of the Criminal Bar Association, does not see a world of remote trials as one that will deliver justice. Trials, she insists, ‘are about people’ and about the guilt and liberty of an individual. Defendants and witnesses must be in the same place to look juries in the eyes.

There is, says Brimelow, a full range of visual and non-visual cues that are not transferred through a screen. And she says, ‘a trial is real life and not watching a television drama,’ adding that ‘remote hearings can distort and remove the gravity of the situation’.

Lefley concludes: ‘The challenge is not to turn back the clock, but to recalibrate the advances we have made in our technology outside of Covid restrictions, so that remote hearings are used only when convenient and fair to the most vulnerable participants.’

Catherine Baksi is a freelance journalist

1 Reader's comment