Retired judges have much to offer, Lord Dyson, 81, said on Tuesday. Delivering the Birkenhead lecture at Gray’s Inn, the former master of the rolls drew the line at a return to advocacy. But he said there was nothing improper about former judges giving legal advice.

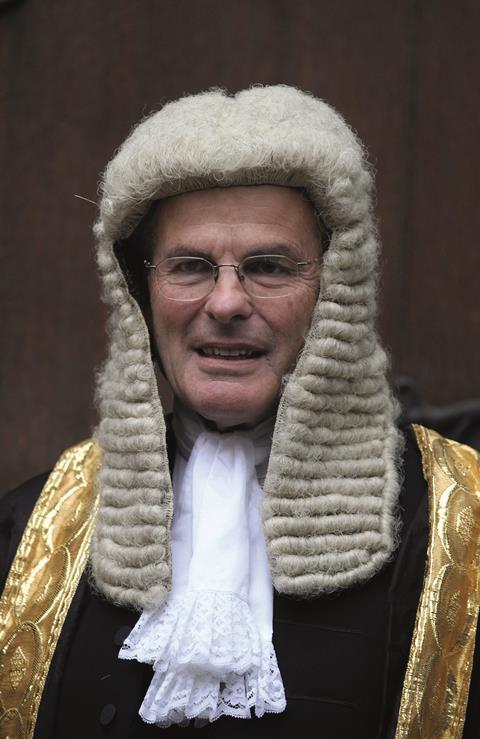

Dyson (pictured below), who sat in the Supreme Court from 2010 to 2012 before serving as head of civil justice for four years, rejoined the chambers he used to lead and accepts instructions just as he did as a barrister. But he no longer takes on work unless it looks interesting or worthwhile, he told me in an interview this week.

As an example of what retired judges had to offer, he mentioned his work on cases brought against the Post Office by sacked postmasters. In a process known as early neutral evaluation, he had been asked to assess what damages a court would award them for non-pecuniary losses.

Both sides were happy with the outcome, he explained. ‘I wrote quite a long decision and I’m told that everybody accepted what I said. The result has been that they will not need to go to court and have a long and expensive hearing to determine these difficult questions.’

We discussed the advice Lord Neuberger had given the Post Office in 2019, when it was seeking to persuade Mr Justice Fraser to withdraw from the litigation brought against it by Alan Bates and other former postmasters. Dyson saw nothing wrong in a former Supreme Court president advising a client confidentially on whether Fraser should recuse himself for apparent bias. The problem, he told me, was deploying Neuberger’s advice in court.

The Post Office had instructed Lord Grabiner KC to make the recusal application. ‘And I am not the only judicial figure or barrister that has looked at this,’ Grabiner told Fraser when asked to explain the delay. ‘It has also been looked at by another very senior person before the decision was taken to make this application.’

In the end, Fraser dismissed Grabiner’s application and his decision was upheld by the Court of Appeal. But Dyson thought Grabiner had been wrong to imply that his argument was supported by a ‘very senior person’, given that Neuberger had now joined Grabiner’s chambers.

‘He could deploy all the arguments that Lord Neuberger had put forward… as part of his submissions before Mr Justice Fraser,’ said Dyson. ‘But what he should not have done was to say, these are my submissions and, what’s more, they are supported by a very senior figure.’

Would it have made any difference if Neuberger had been a leading barrister rather than a former judge? Dyson thought not; a submission rested on its own merits, regardless of who had endorsed it. But he certainly thought that retired senior judges should not appear on behalf of clients in court or even make written submissions. That could have an undue influence on the judge hearing the matter.

Dyson sees no need for former judges to be regulated in the same way as barristers or solicitors. ‘I’m not aware that there’s any real complaint about the way retired judges go about their business,’ he told me.

But I wonder how sustainable that position is. In the latest edition of Public Law, Patrick O’Brien and Ben Yong argue that it is acceptable for judges to return to legal practice but they should first obtain a practising certificate from the Bar Standards Board or the Solicitors Regulation Authority. One or two have already done so.

The two academics call for ‘non-binding but robust guidance that former judges who wish to provide legal services should opt into professional regulation’. Dyson’s riposte is that ‘enforcement of non-binding guidance is a contradiction in terms – and yet if guidance were not to be enforced, in what sense would retired judges be subject to regulation at all?’

His approach – which seems to be shared by the bar regulator – is that retired judges pose no regulatory risk to the profession. But O’Brien and Yong argue that ‘the unique position of former judges gives rise to more general risks to the justice system’.

I would regard these as reputational risks. Neuberger sits as a judge of the Hong Kong Court of Final Appeal. So does another former UK judge, Lord Hoffmann. Dyson told me he thought they should no longer continue to sit. And he began his lecture by recalling that Lady Hale had signed an open letter in which she asserted, erroneously, that the International Court of Justice had found a plausible risk of genocide in Gaza.

The former master of the rolls thought it acceptable for retired judges to give media interviews and discuss their past judgments, but only if they did so in a restrained and responsible way. What former judges say – and do – really matters.

joshua@rozenberg.net

5 Readers' comments