There is no stopping the relentless rise of data. The amount now created and held by corporate clients is growing at a rate of 40% annually – fuelled in part by the post-pandemic shift towards remote communications.

In the litigation context, data volumes are growing faster than human-only disclosure review teams could possibly keep up with. Five years ago, a 50 gigabyte case with around 250,000 documents would have been considered fairly large. Today, the smallest iPhone available has the capacity to hold 128 gigabytes of data. Indeed, in a recent report to the Civil Procedure Rule Committee, Vijay Rathour, a disclosure technology provider at Grant Thornton, said his firm is now routinely processing claims involving 1 terabyte of data – which is 1,024 gigabytes. One current investigation – not even the biggest – encompasses 40 million reviewable documents.

It is against this backdrop that radical disclosure reforms were introduced in the Business and Property Courts (BPC); initially as a pilot in 2019, and then – with some tweaks along the way – becoming permanent last October. Things have seemed rather quiet on the disclosure front since then.

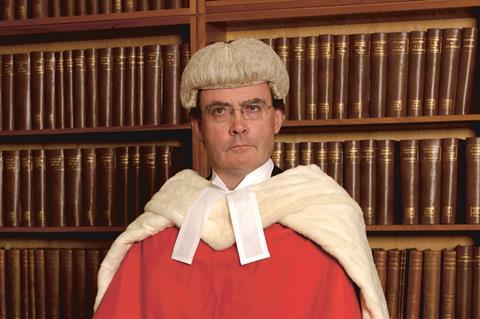

But last month Sir Julian Flaux (pictured), chancellor of the High Court, gave a comprehensive speech on the topic. It is no secret that many litigators deplore the new disclosure regime. Their biggest criticism is that it piles work on to the early stages of a case, which ends up being a wasted effort in the many claims that settle. Addressing this point, Flaux said: ‘There have been complaints that the new system front loads work and cost. But I wonder whether that is really so?

‘Can it sensibly be said that allowing parties to proceed through disclosure without any such engagement, thought and focus will lead to an efficient outcome when it comes to the review and production of data? Do we really want a situation where parties can dump vast quantities of documents on the other side as a litigation tactic? Or where parties have failed to discuss how such documents should be produced from a technical perspective?

‘Or where parties are having to undertake searches across a far larger body of data than is proportionate, simply because there has been no discussion about this or parties have been like ships that pass in the night so far as disclosure is concerned?

‘All too often that was the position [under the old rules] in business litigation, and that is why users, such as the GC100 [group of general counsel of large corporates], made it clear that a new approach was required.’

Flaux urged judges, lawyers and clients to ‘support the change in culture’.

On a more practical note, he offered some advice for litigators grappling with the new rules. One area that has caused problems from the start is the ‘list of issues for disclosure’. Flaux said BPC judges had seen lawyers producing ‘massive’ disclosure lists that leave ‘no issue unturned’. Examining why they did it, he noted that ‘lawyers like detail’; they were worried they might miss the ‘mythical smoking gun’; they didn’t trust their opponents; and they thought a collaborative approach might make them look ‘soft’. But Flaux remarked that, while these factors were understandable, they were not helpful – and the disclosure list must be as ‘short and concise as possible’.

He added: ‘Compromise is needed, but not if it results in taking the line of least resistance and agreeing a list that is far longer and complex than is needed. If there is a fundamental difference between the parties – 10 short issues against 30 lengthy ones – it is very likely that the court can give guidance speedily and almost certainly without a hearing.’

But when things do get to a hearing – namely the CMC – Flaux was very clear on what the court now expects. Parties must show four things: ‘genuine engagement’ with disclosure; a ‘proportionate’ approach; a ‘clear methodology’; and only ‘few differences’ left for the court to resolve. The judge warned that it is ‘unacceptable’ to turn up at court with ‘widely differing’ lists of issues for disclosure, and to then expect the court to settle these at the CMC. If the parties are locked in disagreement, this must be sorted out earlier, by seeking ‘early guidance’ from the court. Failure to follow these steps risks the CMC being adjourned with an adverse order for costs, he warned.

Yet while the court wants parties to have largely agreed on the directions sought, do not expect it to simply rubber-stamp them. On the contrary, parties should expect to be ‘interrogated’ on the directions agreed, said Flaux.

And who should be in the line of fire of the judge’s questions? Not barristers, who may have been briefed only shortly before the CMC. ‘In relation to disclosure specifically, the solicitors who have had day-to-day conduct of the preparation for the CMC may be in a much better position to assist the court than counsel,’ asserted Flaux. So solicitors now have an extra incentive to follow the disclosure rules to the letter – whatever they may think of them privately.

Rachel Rothwell is editor of Gazette sister magazine Litigation Funding, the essential guide to finance and costs. For subscription details, tel: 020 8049 3890, or click here

No comments yet