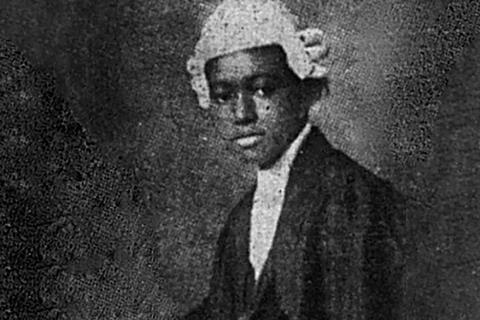

Stella Jane Thomas (1906-1974) was the first West African woman to be called to the Bar of England and Wales at the Middle Temple. Called on 10 May 1933, by 1935 she had returned to West Africa and registered as a barrister at the supreme courts of both Sierra Leone (October 1935) and Nigeria (November 1935), thus enshrining her in history as the first woman lawyer in West Africa. Practising in her brother’s chambers until 1943, she then became the first woman in West Africa to accept a (quasi-) judicial appointment as a magistrate.

Thomas was born in Lagos, Nigeria, of Sierra Leonean descent. She was one of the Yoruba people, an African diaspora who reached from Nigeria to Benin. Her parents were Josetta Mary Thomas and Peter Claudius Thomas, a successful businessman and trailblazer. He was the first African president of the Lagos Chamber of Commerce and the first African to have European employees.

Schooled in Freetown, Sierra Leone, Thomas travelled to England in 1926, behaviour described as ‘rare’: an unmarried black woman travelling to England as a student. Many texts describe her as having studied at the University of Oxford and as being a member of its West African Students Union. However, the Bodleian Library does not record Thomas having matriculated in their indices up to and including 1932; further, her 1933 Middle Temple ‘Call Form’ leaves her university education blank. Her Middle Temple admission application describes her as having passed the Cambridge Schools Certificate. However, there are many inconsistencies in the numerous, but mostly one-paragraph, records of her life in other histories.

On 12 December 1929, she was admitted to the Middle Temple. Having passed her final bar exams in December 1932, she was later called to the bar alongside her elder brother Stephen, who would go on to become the first chief justice of the mid-western region in Nigeria. Another brother, Emanuel, was also a member of Middle Temple, but he was never called. Emanuel later became the first RAF-commissioned African; he flew for Britain in the second world war.

Thomas was one of the founding members of the League of Coloured Peoples, a civil rights organisation open to all races. The league advocated for the end of the colour bar. It had 12 centres, a journal called The Keys, organised social activities and lobbied for change.

Thomas performed in a play at the YMCA, ‘At What a Price’, by Una Marson, the first black woman to be employed by the BBC. The Guardian commented on Thomas’s sheer beauty as she walked across the stage in an orange dress. While the play failed to make money, it brought home to the British public that Africans could manage their own affairs.

In 1934, Thomas openly challenged historian Dame Margery Perham at a 1934 lecture at the Royal Society of Arts. The only African woman to participate in the discussion, Thomas argued that Africans should be involved in and consulted on the process of seeking to resolve the problem of Africa. The former governor general of Nigeria, Lord Lugard, was in the audience, and Thomas addressed him directly to criticise the ‘dual mandate policy’, stating that it made puppets out of traditional rulers and chiefs.

By 1935 Thomas had returned to Lagos, joining her brother Stephen’s chambers.

She was made a magistrate in 1942 or 1943. There is evidence of her magistracy: she sentenced Alice Ewo to a fine of £5 and 10 shillings, or one month’s imprisonment with hard labour, for selling six cigarette sticks for 6p instead of the fixed price of five cigarette sticks for 4p. In November 1943 she married a fellow Nigerian barrister, Richard B Marke, also of Sierra Leonean descent and with whom she had studied. Thereafter known as ‘Mrs Marke’, her marriage and profession gave her an influential status in public life.

We know nothing of Thomas’s life after her marriage. Her trailblazing would have been lonely because change was slow. It was not until 1947 that Mrs Renner (Modupe Alakija) became the second female lawyer in Nigeria. From 1949 to 1960 another 18 women would join them, compared with more than 300 male lawyers. Modupe Omo-Eboh, called to the Bar at Lincoln’s Inn, went on to become the first female judge in Nigeria when she was appointed a judge of the High Court in Nigeria in 1969. By 2015 there were just 10 senior women judges. There has only been one woman Nigerian Bar Association president, and of 475 senior advocates, about 20 are women. Women lawyers in Nigeria, like women in the UK, continue to suffer from discrimination both in and out of the courtroom.

Thomas is an important figure for diversity. Her life demonstrates that Africans have a long tradition at the bar of England and Wales. By practising as a barrister and sitting as a magistrate she broke the mould in England, Nigeria and Sierra Leone. This engagement with her history gives context to the discrimination faced by Africans then and now. However, it enables us to go beyond narratives of discrimination and slavery, showing achievement, success and trailblazing. Her life also shows us the value and power of education.

Professor Judith Bourne is dean of the CILEX Law School. This article was adapted from Women’s Legal Landmarks in the Interwar Years: Not for Want of Trying, published by Bloomsbury

No comments yet