In December 1919 seven women were appointed to the magistracy, a hitherto wholly male domain. They must have received a very mixed welcome in the retiring room, from warmth to downright hostility. ‘Women have not the judicial mind…’ wailed Lord Walsingham, fifteen years a stipendiary, ‘Their more sensitive souls are always hampered by some sentimental consideration to the doom of justice…’ (Pearson’s Weekly, 1920).

But those pioneering magistrates were not the type to be suppressed. Ada Summers was already Mayor of Stalybridge and chaired a council chamber while Gertrude Tuckwell had been active for years in the Woman’s Trade Union League. Middle-aged and middle-class, these women were rooted in the establishment. Since paid work was a taboo for ladies they had devoted their considerable energies to public service such as Girls’ Clubs, the Railway Women’s Guild and Poor Law Unions. In the war they’d served in the Red Cross or the Woman’s Army Auxiliary Corps and replaced men in factories and hospitals. As Victorians, born and bred, their watchword was duty; to family, community and country. Apart from their sex, they fitted into the magistracy just fine.

But it wasn’t all plain sailing. Those first women magistrates were a telling mix of the conservative – who had never supported women’s suffrage - and women so radical that they had experienced the far side of the bench and even prison in their demand for the vote. To them a drowsy traffic court must have seemed pretty dull especially if they had to put up with a weak chairman or a ‘bullying’ clerk. In court they learned about aspects of life never acknowledged by their Victorian mothers - domestic violence, indecency and abuse – though in some courts swear words were written down and passed amongst the men, and the most shocking cases moved to an all male bench.

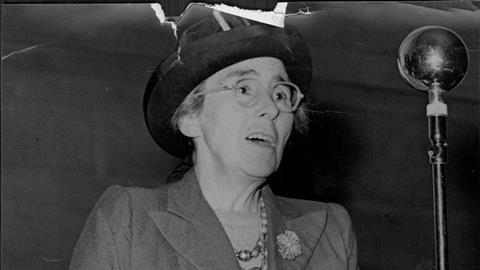

Women magistrates were quick to demand reform. Margery Fry (pictured above) deplored the use of the birch and urged her fellow magistrates to visit borstals; women magistrates questioned whether theft should really be punished more severely than wife-beating and campaigned for women police officers. Geraldine Cadbury was influential in reforming the treatment of juveniles. What’s more, Tuckwell and Fry, alarmed by inconsistencies on the bench, helped set up a Magistrates’ Association to deal with the lack of training.

Today 56% of magistrates are women, whereas Lady Hale has just predicted that it will be 2033 before there is gender equality in the paid judiciary. The reason for this disparity is that although the admission of female magistrates was a radical departure, it did not essentially upset the status quo. And that paradox endures. When I joined the bench in 1986 it was thanks to a piece in Cosmopolitan urging young women to apply, and promising child-minding expenses. I found aspects of the role oddly out of date – key positions on the bench went to the longest servers, the Masonic handshake prevailed, and the question of whether women magistrates should wear trousers was hotly debated at bench meetings. But I was engrossed by the knotty sentencing decisions I had to make, moved by the predicament of victims and, often, defendants, and troubled by the limitations of the criminal justice system. My qualms were overcome by this unique opportunity to be engaged in a vital and ever-evolving area of civic life.

In some respects during the last three decades the magistracy has been ahead of the game. Magistrates accepted sentencing guidelines without flinching and recognised the need for mentoring and appraisal with relatively little protest. But the magistracy, like the rest of the judiciary, is constantly challenged: Can it attract a diverse bench that truly reflects the communities from which it is drawn? Is there sufficient consistency of sentencing? Are magistrates too harsh, particularly on female and BAME offenders? Above all, is the magistracy a relevant institution in today’s society?

As a magistrate, I always felt an outsider in the criminal justice system, even when I was experienced enough to chair the bench or serve on national committees. And that’s as it should be because the lay magistrate is required to be both of the judiciary, and representative of the society she serves. When I was first appointed I was urged not to talk about being a magistrate socially; it would provoke too many awkward questions. And it did feel uncomfortable sometimes. The rebel in me was uneasy that I’d managed to impress my parents by becoming part of the establishment, and my more radical friends were incredulous: ‘I could never pass judgement on another human being,’ they said (accusingly). At interview I’d been asked what I’d do, as a member of CND, if a protester was brought to court accused of cutting the wire at a local military base. That’s the sort of question a magistrate, engaged on many different levels with the community but required to work within the guidelines, has to face all the time.

The magistracy offers a unique opportunity for citizens to ensure that justice is done – a simple phrase but massively complex. In our present uneasy times, the role is ever more relevant. The nature of authority is questioned, expertise debunked, public figures abused, values fundamental to the fair delivery of justice challenged. Magistrates aren’t required to be invisible any more – in fact the opposite. Justice has to be open. The magistracy needs to attract a truly diverse bench so that decisions are made by people who understand our society in all its variety, struggles and inequality, and know that the way we treat our law-breakers is a vital indicator of a healthy nation.

For a great timeline on the history of women in the law see First 100 Years: Timeline.

I am indebted to the doctorate by Anne Francis Helen Logan, submitted to the University of Greenwich in 2002: Making Women Magistrates: Feminism, citizenship and justice in England and Wales – 1919 - 1950.

Katharine McMahon served as a magistrate on West Hertfordshire Bench (which she chaired for three years) and North London Bench. She devised and ran the national courses for Training DC and Bench Chairmen, was the magistrate member on the newly formed Sentencing Council and later served on the Judicial Appointments Committee.

McMahon is the author of ten novels, including The Crimson Rooms and The Woman in the Picture, about a pioneering woman lawyer, Evelyn Gifford. Her latest book is The Hour of Separation.

No comments yet