The conflict in Northern Ireland, commonly known as the Troubles, lasted from 1968 to 1998. Life in the three prisons, Armagh, the Maze and Long Kesh, reflected the struggles – internment, the blanket protests, hunger strikes and strip-searching.

In 1985 I visited Armagh Gaol, the women’s prison, as part of a Commission of Inquiry set up by the National Council of Civil Liberties (now Liberty) to investigate the use of strip-searching in the Gaol.

There had always been strip-searches – on admission and discharge from the prison. But in November 1982 random strip-searching was introduced. This followed an incident the month before when two remand prisoners had been found in possession of two keys which they had picked up in Armagh court house. The main reason given for the use of these extra strip-searches was security. The second reason was self-defence in relation to safe custody of the other prisoners and protection of prison officers from attack or allegations of brutality.

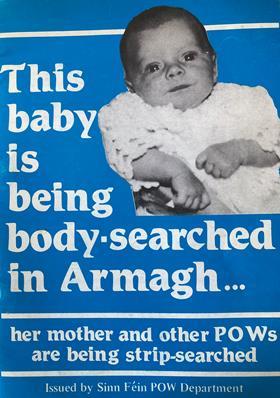

But there was concern that there were other reasons behind the change in procedure, and allegations about the way the searches were carried out and their frequency, particularly for certain prisoners. Questions were asked in the House of Commons. Sinn Fein felt it was a political tool.

In February 1985, after weeks of careful planning and meetings with the Northern Ireland Office, we arrived in Armagh.

I had not been to Northern Ireland before. In Belfast I was struck by the presence of the British army. Soldiers in their uniforms holding heavy guns, walking in the streets and standing at checkpoints, made it seem like a war zone. I felt an underlying apprehension of the sort I had felt in the early 1970s passing through Spain, when Franco’s fascist regime was in power and police walked casually around with guns. It was so unlike the UK I lived in. It was shocking to see what was an everyday situation for the people who lived in Northern Ireland, part of that very same United Kingdom.

There were five of us. Two of us were permitted into the prison. As a barrister, I was one. Armagh, which was about to close, was an old Victorian building with cast iron staircases and long landings with small cold cells leading off, similar to prisons I had visited in England. On one level it was more relaxed than the prisons I was familiar with, as prisoners wandered in and out of their cells. On the other hand, the prison was segregated into three groups: Republicans; Unionists/Loyalists; and non-political prisoners.

In the prison we met remand prisoners and those convicted, a mix of non-political and Loyalist and Republican prisoners. They included Mairéad Farrell, who later was shot dead by the British army in Gibraltar. We spoke to prison officers and the prison governor, and we were also present in the room when, behind screens, a strip-search was taking place.

It was notable that most prisoners were Republican and the vast majority of prison officers were Loyalists. People in control telling the prisoners to take their clothes off seemed almost of itself, in this context, a political act.

We were told the system of searching was random, but we felt it could better be described as arbitrary – some people were picked out. An example we were given was a woman who had been acting suspiciously in her cell. She was strip-searched and an illicit note found in her nostril. Clearly, a strip-search was not necessary for the note to have been found. It was hard not to see the strip-search as a humiliating punishment.

We also went to the court building, which was just across the road from the prison. We were not searched. We were able to walk around, visit the toilets and then sit in the public gallery. A prisoner came in, accompanied by an escorting RUC officer (that is, not a prison officer). She passed within inches of the public gallery benches. Even if they knew who we were and were perhaps watching us, it seemed a very relaxed approach to security. It seemed that the prison service and the police service did not communicate to sort out any issues, which would have been easy enough to do. Instead, what was clearly an ineffective system of security was taken out on the prisoner.

We produced a report which concluded that strip-searching was an ill-considered attempt to maintain authority in the prison following years of unrest in the prison community throughout the province.

Twenty years later, in 2006, I heard from Cahal McLaughlin, a film maker and academic, who was creating a Prisons Memory Archive (PMA). The plan was to ask people who had passed through the prisons – prisoners, prison officers, chaplains, educators, other visitors – to record their thoughts, on film, in the prison with which they had been involved.

That seemed to me such a good idea, to have an accessible and sometimes challenging record from the people who were there, a resource to enrich teaching and learning. I was already feeling that English people in particular had forgotten what it was like, how bitter were the differences, and what an extraordinary feat Mo Mowlam MP had achieved, to bring about an agreement.

By now Armagh Gaol was a shell, waiting for demolition. With one cameraman I walked through the building and described what my experience had been like. My recording is now part of an enormous piece of work, housed in the Public Record Office of Northern Ireland. Some of the recordings are available here.

Now the story of the archive has been made into a book, The Prisons Memory Archive.

As Brexit threatens to dismantle the hard-won peace in Northern Ireland it is timely to think back to the reality of the Troubles.

Elizabeth Woodcraft retired from practice in December 2014 and has since become a Door Tenant at Garden Court Chambers

No comments yet