No commemoration of 1914 can overlook the most influential solicitor of all time.

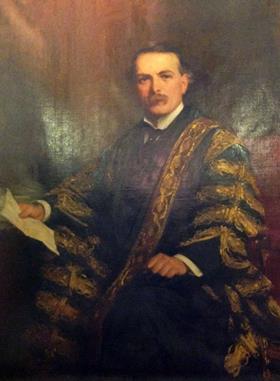

Next time you drop by the Law Society’s HQ in Chancery Lane, look sharply to your left as you walk in. You'll see a life-size portrait of a solemn, dark-robed young man. I walked by for years before I registered who the subject was: David Lloyd George, radical chancellor, prime minister and.... solicitor.

In fairness I can plead that the image chosen by the Society (by Sir Luke Fildes, better known for The Doctor, which hangs in Tate Britain) is not immediately recognisable, lacking the trademark wild hair, tub-thumping gestures and billowing overcoat normally associated with the Welsh Wizard. No doubt the Society thought a dignified, less political, likeness was more appropriate to commemorate the fact that Lloyd George, admitted in 1884, was the first and only solicitor to reach Number 10 Downing Street.

The choice of portrait - and its being ever so slightly tucked away - speaks volumes about the current reputation of the last Liberal prime minister. While anyone with the slightest education in British politics knows Lloyd George's role in the 1909 'people's budget', he is far less celebrated as leader of the 1916-22 coalition. In polls of the greatest 20th-century prime minister, he is generally seen off by Attlee, Churchill and Thatcher, depending on inclination.

Even Liberals regard his premiership and later career - with its corruption, marital infidelities and mutual back-slapping with Hitler - as something to be swept under the carpet.

As we mark this 1914 centenary, this simply won't do. Lloyd George's influence hangs over Britain's role in the First World War like a sea mist in Cardigan Bay; in our decision to enter the war, the road to victory and history's subsequent interpretation of the conflict. Is there a better candidate for the most influential solicitor of all time?

Heaven know's there's enough material to go on. Although his cottage upbringing by a widowed mother and shoemaker uncle was not quite as humble as he later made out, there is no doubt that Lloyd George broke the mould amid 'the dukes' of the Westminster establishment. Even in Wales, as a non-native English speaker and member of an extreme nonconformist sect he was, in the words of recent biographer Roy Hattersley (The Great Outsider , Abacus 2010), 'an outsider among outsiders'.

Lloyd George's interest in the legal profession was sparked by tales of drama in Pwhelli county court – and the influence of his uncle Lloyd, who raised the £100 articles fee and £80 stamp duty the 16-year-old needed to get a start. His employer was Portmadoc (now Porthmadog) firm Breese Jones & Casson, which specialised in land law.

To sit the Society’s Finals young David travelled to London for the second time in his life. ‘I went to Chancery Lane and got admitted in regular humdrum fashion,' he recalled. 'The ceremony disappointed me. The master of the rolls, so far from having anything to do with it, was actually listening to some QC at the time.'

That slight left its mark. While his rank gave him rights of audience only to the most humble courts, this does not seem to have cramped his style. A typical entry from his (highly expurgated) diary, quoted in a 1912 hagiography by Herbert du Parcq, reads: ‘Attending Penrhyn Sessions for first time, opposing transfer of licence of Victoria Inn. Got on, I think, remarkably well. Never felt more fluent, but Bench would not listen to anything. Would not enter into question of existence of licence. We discussed and debated together for three-quarters of an hour, but to no avail.’

It is possible to feel some sympathy for the bench.

Likewise in an (apocryphal) episode during the case that made his name. Lloyd George carted into the court a huge volume on chancery precedents and began reading from the beginning. 'Surely,' said the judge, 'you are not going to read all the way through?'

'If I did Your Honour would know some law when I had done,' he supposedly replied.

That was in the Llanfrothen burial case, a battle to persuade a local rector to comply with the Burial Act of 1880 and allow a quarryman named Roberts to be interred in a consecrated part of the churchyard rather than a plot 'bleak and sinister, in which were buried the bodies of the unknown drowned'.

The case made Lloyd George's name, launching a political career which was to lead to the premiership via those crucial Cabinet meetings of August 1914. Where Lloyd George's voice was a decisive one in taking Britain in to the conflict. Whether motivated by genuine outrage at the violation of Belgian neutrality or scheming ambition will be debated over and over again this summer.

I'm not inclined to judge, only to wish that Lloyd George had more of a presence in English contemporary culture. Possibly it’s my own ancestral chip showing, but I can’t help feeling if he had been Irish or Scots we would have had a blockbusting Hollywood biopic to mark the centenary: George Clooney might be right for the role.

But, you ask, what's this about secretaries and fathers? Readers of a certain age will remember the satirical ditty 'Lloyd George knew my father, father knew Lloyd George', repeated ad infinitum to the tune of Onward Christian Soldiers. The joke's meaning is obscure: a reference to dodgy peerages, adultery, or both.

But in my case it was nearly true: my father was once hired to edit the shorthand diaries of Lloyd George's principal private secretary. The result appeared as Life With Lloyd George (Macmillan 1975). I can't pretend it's a particularly easy read, but it meant that I got to meet the author, A J Sylvester, an ancient but still razor-sharp country gentleman.

Alas I was a sulky long-haired teenager and unimpressed at shaking hands with history. I feel differently now.

Michael Cross is Gazette news editor

1 Reader's comment