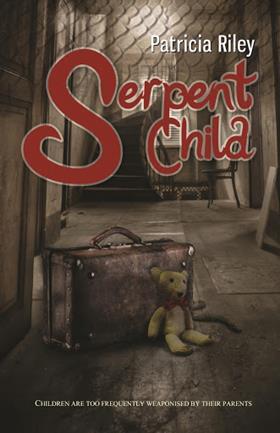

Serpent Child

Patricia Riley

£10, Stairwell Books

★★★★✩

‘Children are too frequently weaponised by their parents,’ reads the front cover of this book. This is a quote from Mrs Justice Parker, who also talked of ‘child soldiers in a separation war’.

Serpent Child is an autobiography which particularly focuses on the dynamics of the relationship, especially in childhood, of the author and her parents who undergo an acrimonious custody dispute. Riley’s father had successfully applied for her to be made a ward of court. Thanks to the 1948 decision of Mr Justice Wynn-Parry, from the age of seven the author spends her term times in a boarding school and half of every school holiday with each parent. With no account taken of her actual views, she describes herself as being parcelled up equally, just as chattels from the marriage had been divided.

In 1950s Britain the social stigma of divorce is strong. The author attends a senior school where the deeply religious staff believe it to be her Christian duty to reunite her separated parents.

The author’s mother is controlling and seeks to turn her against her father, who is equally controlling. On one occasion her mother manipulates Riley to get up in the night while staying with her father to tell him she wants to go home to her mother. Her mother also shared with Riley, when a child, the contents of solicitors’ correspondence resulting from the litigation.

The title of the book comes from a misquotation of King Lear that formed a one-line letter from her father she received at boarding school: ‘How sharper than a throbbing tooth it is to have a serpent child.’ This was during a time the author was refusing to write to her father.

Former chief executive of CAFCASS, Anthony Douglas, contributes an afterword. He says that much of the history of family law is the history of the emancipation of children and a shift from being at the periphery of their own case to holding centre stage. In 1948, he says, the fundamental principle of equality, central to the civic status of all family members in law, was not even dreamt of. In the last 50 years we have moved to a situation where child impact analyses are written in which disputes between parents are seen through the child’s eyes.

This is not just a book for the family law practitioner. It is a widely accessible and deeply compelling book about issues which are rarely covered in such depth.

Tony Roe is a family law consultant at Penningtons Manches Cooper

No comments yet