Handbook on Crime and Inequality

Editors: Stephen Farrall and Susan McVie

£225, Edward Elgar Publishing

★★✩✩✩

If you want to avoid being murdered you should move to Norway. On the other hand, if you have a death wish there is much to be said for settling in Russia. This book tells you why. It also gives useful tips on how to avoid being robbed – primarily, stay out of cities. These observations are unlikely to figure in the media reporting of a horrific murder or outbreak of mobile phone robberies, but arise from the best research we have into these areas. We have a long way to go, though, before we can be confidently definitive about the causes of crime and the best way to deal with it.

The book’s very bare bones of a conclusion are clothed in a great deal of heavyweight statistical information and discussion about the correct methodology. For example, the Gini Index, used in the book, which is well established as a tool for attempting to analyse financial inequality and has been around for over a hundred years, is still rough and ready at best, and has no settled and universally understood interpretation. Equally, the quality of research to produce the statistics can vary greatly.

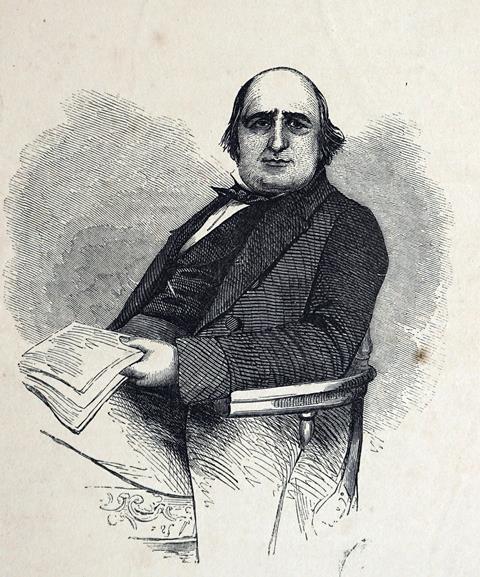

The Victorian researcher Henry Mayhew (pictured) dealt with the question of what makes people behave as they do by interviewing and recording the lives of hundreds, especially those he would probably not have invited around for lunch. His research is illuminating even today and full of human interest. It lacks statistics and methodology, as a modern academic would define them, and none of his case studies reached this book. Given a choice between an account by a crossing sweeper of his daily life and a statistical graph, I suspect most criminal lawyers would prefer the life story.

However, a book like this has its place. It consists of a useful introduction and numerous chapters written by a worldwide selection of academics, using more-or-less scientific methods to evaluate the relationships between financial and social inequality and crime.

The knowledge supplied by media reporting is focused on the hard cases which used to make bad law, but which now result in emotionally driven increased sentencing guidelines or criminalisation of activity that is at least arguably mischaracterised as such. In order to guide our legislators’ thinking, hard evidence, obtained in ways explained as fully as possible and as scientifically as possible, surely must carry more weight than relying on the emotional outpourings of a grieving relative – though if that outpouring matches the statistical evidence it has its role to play, just as the crossing sweeper’s tale did in affecting Victorian legislation.

The book is hard going for a lawyer. It is full of sentences that are comprehensible to an academic sociologist or criminologist but probably no one else. Its conclusions will not sway any jury or judge, even if they were allowed to consider them. However, anyone connected with the legal system who is concerned with the way society is or may be changing will find nuggets of interest here, with the makings of a framework for future rational action to cope with these changes.

Michael Freeman is a retired Shropshire solicitor

No comments yet