The blood of miscreants suffering Anglo-Saxon justice in the form of branding, blinding or castration seeps through the pages of this book.

Potter slashes through the period 600-1500, with King Aethelstan commanding that male thieves be stoned and females burned and their corpses put on public display. Since upholding law and order ‘was a crucial contribution of the Anglo-Saxon period to the development of English law’, kings began to exert more influence in local justice. Hanging, beheading and mutilation became more common.

Under Henry II, royal justices were ‘not the mere mouthpieces of the king’ and ‘were becoming a corporate body: the judiciary’. In 1219, Henry III sought new means of criminal proof. Trial by ordeal came to an end with the first recorded criminal jury trial, held in 1220. ‘The jury was a regulated mob, in which private revenge was turned into public justice,’ Potter observes.

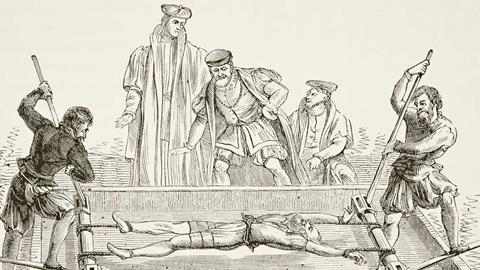

A harrowing picture emerges of 1500-1766: ‘Miscreants standing before [the Star Chamber] were standing before the king himself.’ Those guilty of offences such as rioting or fraud were put in the pillory, whipped, branded or mutilated. The king could warrant torture and between 1540-1640 this was sanctioned 81 times. Manacles and the rack (pictured) were the chosen methods.

Law, Liberty and the Constitution: A Brief History of the Common Law

Harry Potter

£25, Boydell Press

In ‘The Transformation of the Law 1766-1907’, Potter turns to those who gave succour to the modern trial process. In felony trials, William Garrow declared a general right of defence using a trained lawyer, and in more than 1,000 cases at the Old Bailey was ‘to the fore in discriminating between strong and weak evidence’. Thomas Erskine was renowned for his cross-examination and oratory.

In ‘The Rule of Law 1907-2014’, Potter is insightful on the Nuremberg war trials. British prosecutor Sir David Maxwell-Fyfe’s ‘questioning of Goering was a masterclass in how to do it’. In the Nuremberg judgment – ‘perhaps the most far-reaching legal judgment of all time’ – Norman Birkett declared that a charge of conspiracy as ‘continued planning, with aggressive war as the objective’ has been ‘established beyond doubt’.

Potter lacerates the jargon and marches through a long timeline to produce a slim, superbly written account of the common law.

Nicholas Goodman is a sub-editor at the Law Society Gazette

No comments yet