Quantifying diminution of value as a form of damages poses problems for litigators and the courts.

Assessing damages has never been straightforward but quantifying diminution of value as a form of damages is increasingly posing some problems for litigators and the courts.

The situation is comparable to selling or refinancing a car. If your car has been damaged in an accident, the evidence of repairs can negatively affect its value should you later decide to sell or refinance it, notwithstanding the general depreciation of the car. This reduction in value is also known as diminished value. To the insurance world, it was a concept developed to estimate loss of value following an accident. However, the calculation can be decided in very different ways dependent on the entity valuing it. But that is enough about cars.

In the legal world, a recent case has touched upon how best to approach the calculation of diminution in value and has highlighted the flexible approach to be taken by parties. Moore and another v National Westminster Bank [2018] EWHC 1805 (TCC) involved the purchase of a flat via a loan secured by way of a mortgage with a bank. A mortgage offer was released to the buyers of the flat without the bank obtaining a Home Buyers Report, despite the buyers’ instruction to the bank to obtain one. The buyers were left with the impression that the report had been favourable, but in fact the flat was in a poor condition and needed extensive repair work. The purchase was completed and the buyers became aware of the condition of the property. The buyers could not afford the repairs and issued a claim against the bank, stating that had they received the report, which would have alerted them to the issues, they would not have purchased the flat.

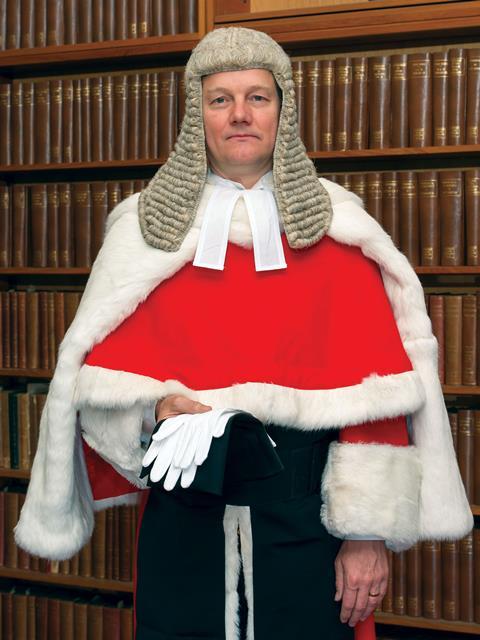

A debate ensued between the parties as to the correct measure of damages in this case. The buyers contended that it was the cost of repair, but the bank was of the view that it would be a sum equal to the decrease in value of the flat (which is the usual approach). The first instance judge found in favour of the buyer. The bank appealed to the Technology and Construction Court, but failed. The appeal court judge, Mr Justice Birss (pictured), refers to four key points which strike at the heart of litigation strategy and the fundamentals of how to calculate diminution in value.

First, the diminution in value rule in Phillips v Ward [1956] 1 WLR 471 (that the correct measure of damages is a sum equal to the diminution in value of the property) is almost always appropriate where property is acquired following negligent advice by surveyors or solicitors – but it is not an invariable rule and should not be applied mechanistically. In essence, parties should ensure that they look at the particular circumstances of a matter in the round and apply a flexible approach. In this case, Mr Justice Birss held that diminution in value could be determined by the cost of repair as argued by the buyers.

Second, diminution in value can in an appropriate case be determined by the cost of repair. In the circumstances of this case, the lower court judge had been entitled to take the view that the costs of repair represented the only practical indicator of what the diminution in the value of the asset was.

Third, Mr Justice Birss flagged that it is a common occurrence in assessing damages based on valuation that the paying party is only prepared to take one view on the reduction to damages and is not prepared to advance an intermediate position, even as a fall back. While he stated that receiving parties do this as well, he noted that in his experience this occurred more often by paying parties. In this case, Mr Justice Birss’ impression of the appeal hearing was that if he had not asked counsel for the bank for an intermediate diminution in value sum, none would have been advanced, commenting further that ‘the imperatives of advocacy often drive parties to adopt this tactic but it can backfire’. The middle ground is often an area where litigators hesitate to enter, but, as shown here, without considering an alternative position, one could end up costing a client more money.

Finally, what stands out from this judgment is Mr Justice Birss’ comment that while it would not have undermined the lower court’s decision, it was open to the lower court judge to take a different approach, and more specifically it was also open to that judge to propose a different calculation for the diminution in value, lower than the cost of repair and to have awarded that. This is an interesting proposition, highlighting again the importance of providing an intermediate position.

As has been seen by Mr Justice Birss’ reasoning in this case, the calculation of diminution in value is, as the insurance concept, a flexible notion and is open to interpretation depending on the circumstances of a particular case. Practitioners should therefore be alive to this when advising clients on claims involving diminution in value.

Georgina Squire is a committee member of the London Solicitors Litigation Association and head of dispute resolution at Rosling King LLP. Avneet Baryan, an associate at Rosling King, also contributed to this piece

No comments yet