The recent judgment of Mr Justice Calver in Invest Bank PSC v El-Husseini demonstrates the hard stance a court will take when parties fail to adhere to court timelines, thus hindering the efficient conduct of litigation.

The case involved a dispute over alleged fraudulent asset transfers whereby Invest Bank, a United Arab Emirates-based bank, claimed that Mr El-Husseini transferred assets at an undervalue to avoid paying debts and putting his assets out of reach to creditors. In doing so, Invest Bank challenged the authenticity of the divorce papers between El-Husseini and his ex-wife. The bank asserted that while the couple may formally have divorced in August 2017, they continued to behave as though they were married.

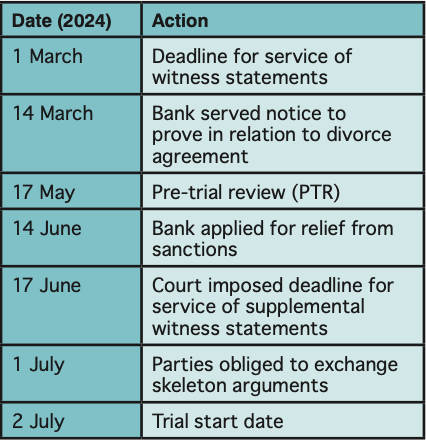

Invest Bank filed a notice to prove (the notice) to challenge the authenticity of the divorce papers. However, the notice was served almost two weeks late with an application for relief from sanctions being eventually submitted three months later. The bank’s failure to act promptly meant the trial timeline had to be adjusted to accommodate the application.

Timeline

Interpretation of CPR 32.19

The first consideration for the court was whether an application for relief from sanctions was necessary. To determine this, the court looked at the meaning of Civil Procedure Rule 32.19 to consider whether the service of the notice on 14 March 2024 was indeed regarded as late service.

Calver J held that a party would be deemed to admit the authenticity of a document disclosed under Part 31 unless it served notice that it wished the document to be proved at trial, with that notice to be served by the latest date of the primary witness statements, not supplemental witness statements.

Otherwise, he considered that, as supplemental witness statements could potentially be served at any time before trial, there was a risk that there would not be enough time to gather the necessary evidence to establish the genuineness of the challenged document.

Accordingly, as of 2 March, Invest Bank was deemed to have admitted the authenticity of the divorce agreement so the bank was almost two weeks late with its service of the notice on 14 March.

Calver J held that the purpose of CPR 32.19 is to ensure timely notice is given of any challenge to authenticity so that the party whose document is so challenged can determine what evidence it is necessary to obtain to meet the challenge.

Relief from sanctions

Since the notice was not served in time, the bank required the court to grant an extension of time pursuant to CPR 3.1(2)(a) and relief from sanctions under CPR 3.9 following the three-stage test set out in Denton v TH White Ltd [2014] 1 WLR 795:

Stage 1. First, the court must consider the seriousness and significance of the failure to serve the notice in time. Invest Bank had served its notice almost two weeks late, made its application for relief three months later and the nature of its challenge to authenticity had only been articulated the day before the trial was due to start on exchange of the skeleton arguments. The defendants were, therefore, deprived of a proper opportunity to adduce further witness evidence to counter the case advanced so that the efficient conduct of litigation had been adversely affected.

Stage 2. The court must consider the reason for the breach of time limits. There was no good reason for the delays, which Invest Bank admitted was an ‘oversight’. Three months had passed since the notice was served with the application for relief from sanctions only issued on 14 June. At the PTR in May, this procedural point was raised but the application was still not issued until a month later.

Stage 3. The court must consider the need for litigation to be conducted efficiently and at proportionate cost. The bank’s failure to act promptly meant the trial timeline had to be adjusted to accommodate the application. The biggest hurdle, however, was that the use of the notice was a back-door attempt to allege forgery, which the bank had not pleaded. The point of challenging authenticity was to argue that the document was forged, and, if allowed, that would involve adducing expert evidence as to forgery and amending the pleadings, which would inevitably disrupt the trial timetable. However, there was no pleaded case as to the genuineness of the divorce agreement; it was not alleged that the divorce agreement was a forgery or a sham, so granting relief would serve no useful purpose.

Conclusion

The court ruled that the bank’s late service of almost two weeks was serious and without good reason. It had caused significant disruption to trial preparation and the court was therefore satisfied that it was not appropriate to grant the bank’s application for relief from sanctions. Furthermore, the court ruled that, in this case, a notice was an inappropriate vehicle to challenge the document.

This case serves as a reminder to adhere to court timelines. Failing to meet deadlines and filing inappropriate notices wastes court time. Such failures are not treated lightly and can result in severe consequences.

John McElroy is vice-president of the London Solicitors Litigation Association and partner at Fieldfisher. Jessica Solsberg is a solicitor at Fieldfisher

No comments yet