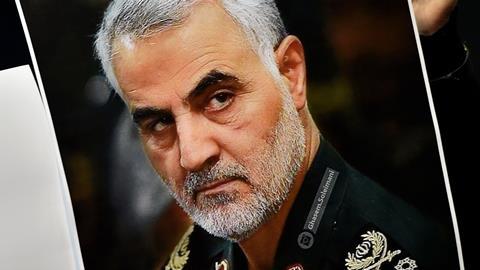

On 3 January 2020, Iranian major general Qassem Soleimani was killed in a targeted US drone strike leaving Baghdad International Airport. Other high-ranking soldiers with political connections were also killed in the strike. On 7 January, Iran had launched missile strikes against two U.S. military bases in Iraq, with no fatalities, and within days, the U.S. filed a formal letter with the United Nations claiming that the Soleimani strike was an act of self-defence in accordance with Article 51 of the UN Charter.

The uneasy interplay between legal regimes, namely the international laws regulating inter-state use of force, humanitarian law and domestic military law underpins the Soleimani controversy. Specifically, the incident has raised the following questions:

- Was the U.S. acting lawfully under the international laws governing the use of armed force?

- What is the position of these strikes under U.S. military law?

- To what extent is U.S. law consistent with the responsibilities enshrined under international law?

International law regulating inter-state use of force

Under Article 51, a state may invoke self-defence to justify its use of force in another state’s territory 'if an armed attack occurs.' This is known as jus ad bellum. A 2010 UN report on 'targeted killings' concluded that the self-defence argument required any response to be imminent, necessary and proportionate. Imminence is given a strict reading; it can only refer to a threat which is, according to the report, 'instant, overwhelming and leaving no choice of means, no moment of deliberation.' Necessity demands that there is no alternative to the use of immediate military force. Proportionality means that the military action deployed can go no further than necessary to neutralise the threat.

It remains controversial whether pre-emptive self-defence can ever be a legitimate basis for the rule of force. A few hours after the strike, the US Department for Defence claimed that 'General Soleimani was actively developing plans to attack American diplomats and service members in Iraq and throughout the region.' Although this suggests that ‘imminence’ was perceived, there are two notable difficulties with this rationale. The first is evidential – the U.S. has failed to provide any evidence of a threat which 'left no choice of means, and no moment of deliberation,' as described by Agnes Callamard, the U.N. special rapporteur on extrajudicial executions. Mere assertions of a threat are insufficient. The second is conceptual. Evidence of past activities of Soleimani and his involvement in human rights violations in Iran, Syria, Iraq and elsewhere do not possess the timeliness element to make any threat tangible, immediate and, most importantly, a threat to U.S. security in particular.

Domestic law

The Trump administration has hinted at two rationales through which the killing of Soleimani might be legal under domestic law: that the general was a legitimate wartime target and that killing him was an act of self-defence in light of the imminent threat he posed. In terms of the former, the administration cited the 2002 bill Authorisation for Use of Military Force Against Iraq Resolution, passed to enable the 2003 invasion of Iraq. If the administration establishes that Mr Soleimani’s activities in Iraq made him an adversary in that conflict, it can deploy the broad wartime legislation to target him. This presents a normative difficulty: at what point should the war in Iraq be regarded as ‘over’, such that American activities in the region can no longer be nominally justified under 2002 legislation?

In terms of the latter justification, the rationale that Mr Soleimani posed an 'imminent' threat alludes to the stringent internationally-recognised standards of jus ad bellum. However, this terminology derives from Obama’s drone strike policies rather than international law, and there is evidence that the U.S. government uses a significantly more expansive definition of 'imminent' – someone whose past actions suggest they may pose a future threat.

Dr Ralph Wilde, an expert in public international law at University College London, commented: 'Since 9/11 the US has taken a view that self-defence can be justified to prevent more longer-term attacks, when the attack is being planned, but is not imminent. The Obama administration used this argument to justify drone strikes.'

It is perhaps unsurprising that the Soleimani killing has highlighted a dissonance between the legal definitions deployed in American domestic policy and their counterparts in international law. Although much commentary notes the exceptionality and illegality of Soleimani’s killing, there are two important rejoinders. The first is that the legal definitions of what can be 'targetable' under drone strikes and what is an 'imminent' threat derive from Obama-era policy making, and at least legally represent a continuation of this policy.

The second is that killings such as this represent a challenge to international law not only because they directly violate that law but also because they challenge such law through defying straightforward legal categorisation. As described by Rosa Brooks, law professor at Georgetown University Law Centre, drone strikes 'constitute a serious, sustained and visible assault on the generally accepted meaning of certain core legal concepts, including “self-defence,” “armed attack,” “imminence,” “necessity,” “proportionality,” “combatant,” “civilian,” “armed conflict,” and “hostilities.”'

The reality is that it remains difficult to extricate legal definitions relating to foreign military policy from their political context, and the indeterminacy and ambiguity of the law governing the use of armed force might create space for post hoc legal rationalisation. In a context of perpetual military conflict between state and para-state groups which might not necessarily engage just ad bello, or humanitarian law, this strike could be part of a broader trend to develop technical legal doctrines which are increasingly permissive of the use of force in different, nominally peace-time conflicts. As Samuel Moyn concluded, if we treat the killing of Mr Suleimani as solely a matter of legal interpretation, 'we miss the point of talking about it.'

Sailesh Mehta and pupil barrister Helena Spector of Red Lion Chambers

No comments yet