What influence does Magna Carta have on modern-day court judgments? Kevin Bonavia looks at some recent cases.

Amidst all the attention recently poured upon Magna Carta, culminating in last week’s festival at Runnymede, there can be no doubt as to the importance of its influence in the development of the rule of law in this country and far beyond. But what relevance does an 800-year-old charter have on today’s practitioners of law?

The original Magna Carta is not expressly recognised in today’s law: it barely survived the summer of 1215, with King John resiling from his agreement to grant a series of concessions on grounds of duress. But a weak Crown needed to earn consent from both the church and the nobility and further, shorter versions were granted by John’s successor Henry III. It is the 1225 version that was later encoded into statute by Edward I’s parliament in 1297, and it is the bare remnants of this statute which survive today.

Of the 61 provisions set out in the 1215 version (as divided and numbered by Sir William Blackstone in 1759), most were repealed between 1828 and 1969 on grounds of obsolescence, for example the restriction of fish weirs on rivers (a significant barrier to 13th-century trade), but three remain on the statute book.

First, the freedom of the church is confirmed: ‘…that the Church of England shall be free, and shall have all her whole Rights and Liberties inviolable.’ (Chapter 1, 1215 and 1225.) This issue was of crucial importance to the governance of England at a time when the church owned substantial land and administered its own courts. Since the Reformation, the Church of England has been welded to the state with the monarch as its supreme governor, and this provision is likely to remain dormant perhaps until steps are taken to disestablish the Church of England.

Second, the pre-existing liberties and customs of the City of London are confirmed: ‘The City of London shall have all the old Liberties and Customs [which it hath been used to have].’ (Chapter 13, 1215; Chapter 9; 1225.) As per the freedom of the church, it is unlikely that this provision will be engaged in argument until such time that there may be moves to integrate the City into wider London government.

Third, perhaps the most famous of all: ‘No Freeman shall be taken or imprisoned, or be disseised of his Freehold, or Liberties, or free Customs, or be outlawed, or exiled, or any other wise destroyed; nor will we not pass upon him, nor condemn him, but by lawful judgment of his Peers, or by the Law of the Land. We will sell to no man, we will not deny or defer to any man either Justice or Right.’ (Chapter 39, 1215; Chapter 29, 1225.)

These are the words that inspired English parliamentarians in the 17th century and American colonialists in the 18th century to achieve revolutionary change in limiting the arbitrary power of government.

Yet, as profound as these words are, they are rarely cited by our courts and still less applied in their decisions. A recent search of reported cases over the past 450 years yielded around 160 citations and no examples where a case was decided on Magna Carta alone (Joshua Rozenberg: Magna Carta in the Modern Age, British Library, 2015).

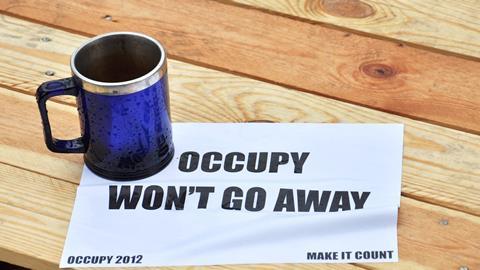

A recent example of one such citation was by the master of the rolls in rejecting the argument made in reliance on Magna Carta by one of the Occupy London protesters camping in St Paul’s Cathedral churchyard in 2011 (The Mayor Commonalty and Citizens of London v Samede & Ors [2012] EWCA Civ 160): ‘He also says that his “Magna Carta rights” would be breached by execution of the orders. But only chapters 1, 9 and 29 of Magna Carta (1297 version) survive. Chapter 29, with its requirement that the state proceeds according to the law, and its prohibition on the selling or delaying of justice, is seen by many as the historical foundation for the rule of law in England, but it has no bearing on the arguments in this case.’

Whilst judges are likely to ignore attempts to pray the aid of Magna Carta without relevance, in a recent Supreme Court case, (Lumba (WL) v Secretary of State for the Home Department [2011] UKSC 12), Lord Collins cited Chapter 39 as a one of a number of ‘fundamental rights’ in holding that the government had been breach of duty in the exercise of its power of detention of foreign national prisoners pending their deportation.

Given the rarity of these citations as a whole, one might fairly assume that the ‘fundamental’ nature of Chapter 39 is merely an ornament used by judges by way of emphasis when a right so obvious as no detention without due process has been violated.

Another reference to the fundamental right found in Magna Carta was a Court of Appeal case (Secretary of State for Justice v RB & Another [2011] EWCA Civ 1608), in which Lady Justice Arden stated: ‘The right to liberty of the person is a fundamental right. It has been so regarded since at least the time of the well-known provisions of clause 39 of Magna Carta, which in due course found its reflection in article 9 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and article 5 of the [European] Convention [on Human Rights].’

Just as medieval monarchs were compelled to reconfirm the provisions of Magna Carta, so its provisions have found expression in later legislation, thereby obviating the necessity of direct reference.

But that necessity may come to the fore again as the government wrangles over how to amend or repeal the Human Rights Act: nothing is so fundamental that it cannot be repealed by parliament, if no longer by an all-powerful and capricious monarch.

In the coming debate over human rights law in this country, now may be the time for both judges and lawyers to state the fundamentally obvious by referring to Magna Carta more often.

Kevin Bonavia is an associate in the commercial litigation, civil fraud and asset recovery department at Peters & Peters Solicitors

6 Readers' comments