Follow our live blog from the public inquiry into the Post Office Horizon scandal

4.50pm: And with that issue of minutes being scrapped still very much to be further discussed, we run out of time. Smith returns tomorrow after the conclusion of evidence from former general counsel Chris Aujard, whose evidence session overran last week.

4.40pm: Smith says: 'I was driving [when Singh told me] and I can recall complaining to him about the influence being exerted over Post Office by the external civil lawyers.

'I can also recall him telling me that an instruction had been sent out and that the typed minutes should be scrapped and if anyone asks then Cartwright King would be blamed.

'I can recall being absolutely horrified and shocked by what I had heard.'

4.35pm: The room goes very quiet as Smith explains his reaction to the request that nothing is kept in writing. He had thought the advice had been accepted that a central hub of minutes be set up, but his understanding from talking to Singh was that minutes of meetings about Horizon should be scrapped.

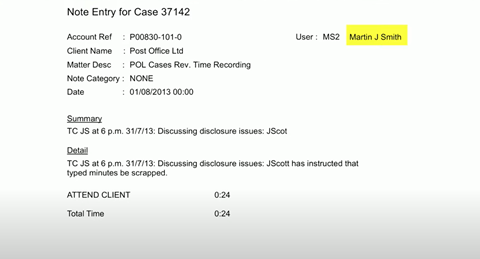

4.30pm: Blake moves on, slightly ominously, to what he calls document retention and destruction. The inquiry sees a note from Smith after Jarnail Smith relayed to him the details of a meeting with Post Office head of security John Scott. Scott advised Singh that typed minutes of meetings be scrapped (below).

4.20pm: The inquiry sees minutes of a meeting of Post Office staff at which Smith was present. This took place on 19 July 2013 - so just after the Second Sight report on issues with Horizon.

Rob King, a member of the security team, states from the outset that no minutes are to be circulated.

Smith is then recorded as having emphasised that any document produced would be potentially disclosable. Andrew Parsons, from Womble Bond Dickinson who also advised the Post Office, commented at this meeting on the 'need to limit public debate on the Horizon issue as this may have a detrimental impact on future litigation'.

4.10pm: The response to CCRC concludes that it is 'incumbent upon POL as a major public institution to take every reasonable step to ensure only the genuinely guilty are convicted and that those who are, or may have been, convicted without good reason, have every opportunity of correcting such a miscarriage of justice'.

Smith says he cannot remember having read the response even though he forwarded it on to the Post Office.

Blake says: 'You are sending a letter to the Post Office which makes absolutely no mention of the kinds of concerns that Post Office had about Mr Jenkins, within days of the Clarke Advice on the impact of Jenkins' evidence and it is not mentioned.'

Smith says he just forwarded the letter and adds: 'I don't believe I gave it any thought at the time.'

4pm: The response to the CCRC goes on to say that the Post Office had relied on a Fujitsu expert witness in many cases, but makes no reference to his evidence being unreliable. This despite Simon Clarke advising only a day before that Jenkins was a questionable witness. Smith says he didn't give it any thought at the time.

Blake asks about the response saying that all cases had been handled by an 'independent and specialist' firm, when Cartwright King had been working so closely with the Post Office. Smith says the reference to independence was that it was not Post Office lawyers running prosecutions.

3.45pm: In July 2013, the Criminal Cases Review Commission (CCRC) asked the Post Office to explain what was happening with Horizon prosecutions. Cartwright King drafted a response which is shown to the inquiry.

The response said: 'Where a defendant asserts, rightly or wrongly, that Horizon is at fault, it is for the prosecution to demonstrate the integrity of the system'.

Blake suggests this was not the way Cartwright King handled prosecutions, as it often relied on defendants to prove Horizon was faulty themselves.

Smith says the approach was not to obtain a report in every case where there was an issue with Horizon.

'The approach was a "wait and see" approach and if the defendant didn't plead guilty then a report would be sought.'

3.25pm: Chair Sir Wyn Williams intervenes to ask why he did not disclose the Jenkins revelation given the matter was 'inextricably linked' to the Second Sight report. Smith says there was no discussion about doing this. Williams notes this is 'surprising' and might be taken up after we come back from a break.

3.20pm: The inquiry hears that parts of the latest internal report were redacted when it was sent out to interested parties. Blake asks Smith whether he was concerned the Post Office had been 'too candid'. He says he did not give it much thought at the time.

3.10pm: With the Second Sight report published and another internal report also casting some doubt on Horizon, Cartwright King wrote to Khayyam Ishaq's solicitors three months after his imprisonment.

The letter said: 'We have formed the firm view that, had the prosecution been possessed of the material contained within the two reports during the currency of the prosecution of your client, we should and would have disclosed that material to you in compliance with our disclosure duties.'

The letter attached the two reports but added that they should not be disclosed to anyone else.

Blake points out that the letter contains no apology or reflection of any wrongdoing.

3pm: Despite the Jenkins conversation a week before, there was concern among solicitors in July 2013 about the imminent publication of the Second Sight report. Smith wrote to in-house lawyer Hugh Flemington to warn that the disclosure of a partial report could 'give rise to adverse publicity and speculation'.

Blake asks whether it should be the job of a solicitor to worry about adverse publicity for their client.

Smith's email went on to say that the Second Sight report would not need to be disclosed in every case and in many cases it would not be disclosable.

2.50pm: Inquiry counsel Julian Blake asks why there was not a sense of urgency about responding to what Jenkins had said. Smith says it was 'reviewed very quickly'.

Singh emailed two days after the Jenkins conversation to say that the expert had volunteered information about two bugs. But Singh did not mention what Jenkins had said about the possibility of other issues with Horizon.

This was days before a trial involving another sub-postmistress at Birmingham Crown Court (pictured below). Singh's email states that Clarke proposed to mention the position 'in private' to the judge in chambers. Smith denies this was an attempt to keep problems with Horizon out of the public eye amid concerns about adverse publicity.

2.40pm: The Jenkins admission, coming just a few months after Kirklees sub-postmaster Khayyam Ishaq had been jailed, would clearly be a significant problem in prosecuting cases. Smith, who ran the Ishaq case, says: 'I expressed concern to Mr Clarke that Mr Jenkins had not raised those bugs during the case against Mr Ishaq... I was quite upset about the position there had been bugs that had not been disclosed in Mr Ishaq's case. I remember being frankly quite angry about that because a man had gone to prison.'

2.35pm: The inquiry sees a transcript of a conversation in June 2013 between Smith and Simon Clarke of Cartwright King and key expert witness Gareth Jenkins. Jenkins was not aware he was being recorded. The Horizon expert told the lawyers 'you can never say there are no more bugs in the system so we've got to be careful about trying to say anything like that'.

Clarke asked to clarify whether prosecutors could not rule out there might be other problems with Horizon. Jenkins replied: 'Yes.'

2.15pm: Jarnail Singh is once again a key element to proceedings. He emailed Cartwright King in March 2013 asking why the Post Office 'cannot simply stay and hold fire in prosecutions where there has been alleged Horizon issues'. This was at a time when serious questions were asked about the basis for prosecutions.

Smith suggests that Singh 'knew more than he was letting on' as he had argued previously that Horizon was robust. He continues: 'It makes you wonder with hindsight exactly what was going through [Singh's] mind. I wonder whether he knew more things than we knew and he didn't impart that to us.'

2.10pm: Defence solicitors Musa Patels made repeated requests for Horizon data and details of the Post Office's Second Sight review, but prosecuting lawyers continued to delay and fail to meet deadlines for disclosure.The inquiry sees an internal email from Smith that said defendant solicitors were 'grumbling about disclosure and the lack of information'.

He admits now that grumbling was an 'inappropriate word' and he would have rephrased it looking back.

'They [the defence solicitors] were quite frankly right weren't they,' concedes Smith.

The defendant in question ended up being jailed for 54 weeks for fraud after a trial.

1pm: Smith says he was aware of a single bug with Horizon that had been detected several years earlier. Says this did not affect his 'robust' stance towards defending the system as this was treated as an isolated matter. The inquiry also hears that Smith changed a draft letter which had pledged to make a disclosure response to the defenc within two weeks. He says this was sensible as self-imposed deadlines were 'a bit daft'.

Inquiry breaks for lunch. Back in an hour.

12.50pm: The inquiry hears that the Post Office did produce a list in 2012 of unsuccessful cases where Horizon had been cited by the defence. This was effectively exactly the sort of material that defendants were requesting and being denied by the Post Officed. Smith says he was not aware of this document at the time as he did not open it and says this was a mistake. He saw the document preparing for the inquiry and says he was 'horrified with what I read'.

12.40pm: Smith is trying to explain why disclosure requests were met with the response that defendants had to particularise what information they wanted.

Smith says: 'I think it was sensible. If someone could give an example of the sort of issues that they encountered [with Horizon] that would enable an expert to look into that.'

Blake asks: 'Was it sensible or was it a tactic?'

Smith responds: 'It was sensible, just in the same way if you were staying in a hotel and left your car keys somewhere, the hotel might say "what room were you staying in?"

'I thought it would be quite useful to have that information so that we could properly investigate and look into the allegations being made.'

12.30pm: Smith does not recall sending the email about a 'fishing expedition' but accepts he sent it.

The inquiry then sees a note from a lawyer with Cartwright King ahead of the trial. Smith says he advised the lawyer to make clear that Horizon worked and that it was the defence's job to particularise problems with the system in order to secure disclosure.

12.25pm: Blake tells Smith: 'The picture we see is one of pushing back against disclosure requests.'

Smith replies: 'Post Office was saying the system was robust. They were clear it was robust and in those circumstances I took the view that any such information should as met the test for disclosure should be disclosed to the defendant.'

12.15pm: Inquiry is concentrating on the Post Office - and by extension Smith's - attitude to disclosure in 2012, when defendants started making requests for Horizon data amid suggestions it was unreliable.

Smith wrote in July 2012 there had been a claim from one defendant that he did not have confidence in Horizon and wanted to put the prosecution to prove money was missing.

Smith's email continued: 'I propose to talk to the barrister whom we have instructed and explain that a robust stance should be taken.'

In another email from September 2012, Smith said the defence were 'clearly aware of the current Horizon issues and are on a fishing expedition. This in my view is a red herring.'

12pm: Charging advice written in 2015 by Smith concluded that it was not in the public interest to prosecute an individual who had exploited flaws in the Horizon system (although his case was not related to shortfalls). Despite there being a good case to prosecute, Smith appeared to urge caution because of the wider effect it might have on the Post Office.

His advice had said: 'There is undoubtedly strong evidence in this case which could be capable of supporting charges of fraud or theft [but] whilst this case does not appear to contain an "Horizon issue", I am concerned about the possible effect of commencing proceedings thereby putting a case into the public domain in which a suspect had said "to be honest there's so many little loopholes in the system"'.

Inquiry counsel Julian Blake asks whether Smith 'confused' what was in the Post Office's interests and what was in the public interest.

'There were times it was apparent those interests would be aligned but there were times it would be clearly different,' he responds.

11.50am: The inquiry is shown an email from in-house criminal solicitor Jarnail Singh to Smith in December 2012 regarding the decision not to proceed with the prosecution of a sub-postmaster as it was not in the business or public interest.

Singh tells Smith that as part of this agreed action the Post Office must say it is 'not connected with the Horizon system integrity and rather simply reflect [sic] the defendants [sic] health and associated issues'.

11.40am: Just a quick note to say Smith did not make any statement at the outset of his evidence, as several witnesses have done.

11.35am: Solicitor Martin Smith is now giving evidence. He was an associate with Cartwright King during the period the firm advised Post Office on prosecutions and occasionally represented the organisation in court. He was admitted as a solicitor in 1996.

Smith has been mentioned a few times during the course of the inquiry, including being named by an investigator as one of three lawyers who may have drafted a statement for him to present in court as his own.

11.10am: Despite the obvious issues with her case, Bowyer carried out a case review in 2013 and concluded: 'This is an extremely worrying case. It is only through good fortune, sensible prosecution counsel and a sympathetic judge that we are not going to have to disclose material which would cause POL a great deal of embarrassment.'

Bowyer tells the inquiry: '[Information] should have been disclosed [to Howard]. I think I got this piece of advice badly wrong.'

Was he worried about embarrassing the Post Office? Bowyer says he was not, and that he is a 'straight edge as a prosecutor'. He adds that the prosecution was deemed safe as Howard had been sentenced on her own basis.

Bowyer is now finished and we go to a break.

11am: The inquiry focuses on the wrongful prosecution of New Mill sub-postmistress Gillian Howard, who was sentenced to a six-month community sentence in 2011 and cleared in 2021.

Two months before Howard made a guilty plea settlement, the Post Office knew there was an issue with an employee at her branch potentially stealing money. She also suggested the shortfalls in her branch account was related to the Horizon system.

10.45am: Henry suggests Bowyer's advice shows he took a 'jaundiced view' of sub-postmasters and was not acting independently when advising on prosecution policy. Bowyer denies that was the case.

The inquiry then moves onto the mediation scheme and hears one sub-postmaster's testimony that the Post Office heard his case, went away and then came back saying they were instructed not to settle unless it was for a token sum.

Bowyer says he was not aware these instructions were being given to the Post Office and that he did not advise on how to carry out the mediations.

10.30am: Having run out of time yesterday, the inquiry has begun with further questions of barrister Harry Bowyer, who gave several pieces of advice to the Post Office as the Horizon system continued to be attacked as unreliable.

In one piece of advice from September 2013, Bowyer warned about key documents which 'may end up in the public domain... with certain unattractive consequences'.

He went on: 'This could create problems should we recommence prosecutions... POL does not want a document in the public domain that provides a route map to how to attack us where we are most sensitive.'

Victims' representative Edward Henry KC says this is exactly why such documents should have been disclosed. Bowyer concedes there were mistakes made over disclosure.