Today's witness is barrister Simon Clarke, who joined Cartwright King in 2010 and started working with the Post Office in 2013

4.55pm: After a quick break and then questions from Gareth Jenkins' representative, we are done for the day.

Sir Wyn thanks Clarke for answering the questions, some of which he says were quite hostile, with 'resolution'.

That is the latest finish we have had for a long time. Tomorrow features Rod Ismay, former head of product and branch accounting at Post Office Limited. The next lawyers to appear will be current and former general counsels Ben Foat and Jane McLeod on 3 June.

We'll be back with live updates then.

4.30pm: Henry asks: 'Were you part of the suppression of material that would have allowed Mrs Misra to appeal promptly to the Court of Appeal?'

Clarke: 'No. The suggestion you put to me is a disgraceful one.'

4.25pm: Henry asks what he would have made of the Jenkins information if he was Misra's defence counsel.

Clarke says he wasn't Misra's defence counsel.

Henry accuses him of trying to 'evade' the question, adding: 'You know it is inescapable you knew the material inside your head was absolutely dynamite, it was a bombshell and would have given rise to an appeal for Mrs Misra as soon as it was disclosed to her.'

4.20pm: Very tense now. Henry, who represents among others Seema Misra, presses Clarke on why he did not see it as his duty to disclose that evidence used in her trial to convict her was fatally flawed.

Henry says: 'It is inconceivable you would not have recognised the importance of disclosure to Mrs Misra.'

After a long pause, Clarke responds: 'Forgive me, is that a question?'

Chair Sir Wyn Williams intervenes to say it was.

Clarke replies: 'Thank you. I disagree.'

4.15pm: Henry says Clarke wrote some 'extremely accommodating' advices for the Post Office, stating they would not be liable for malicious prosecutions. He says that Cartwright King effectively said 'we will throw ourselves under the bus for you'. Clarke does not agree.

Henry says Post Office 'couldn't believe their luck' - hence why Clarke was asked to write a second advice. He adds: 'You on behalf of your firm were basically saying "we will take the rap for malicious prosecutions and POL will be completely absolved".' Henry asks whether Clarke was put under pressure.

'You are wrong,' he replies. 'There were no pressures on me and I am not resistant to pressure.'

4.10pm: After a selection of questions relating to Scotland, Edward Henry KC says he wants to understand Clarke's status: was he advising as a corporate lawyer or as part of a firm of solicitors that had effectively taken on board the entire prosecution facility of the Post Office? Clarke says it was the latter.

3.50pm: Why on earth, asks Stein, did you as a barrister of many years, see that something had gone badly wrong with convictions related to Jenkins' evidence and not go to the court to correct that? Wasn't that part of your ethical duties?

Clarke says: 'My function as a barrister in front of the court is not to mislead the court. There is no circumstance in the Post Office saga in which I had misled a court - therefore I had no duty to go back to the court.'

Clarke adds that he discovered a witness had misled the court but his function was to advise his private client the Post Office what it should do.

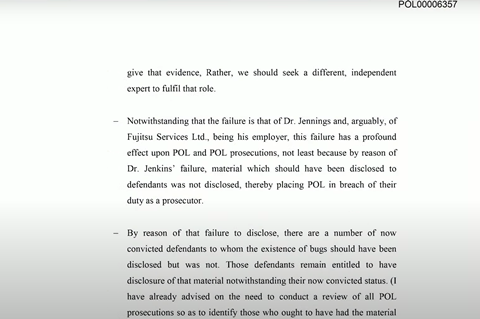

3.45pm: The most combative exchange of the day as Sam Stein KC asks questions of Clarke. He asks whether Clarke ever discussed with Brian Altman KC about whether to investigate the revelation that Gareth Jenkins was an unreliable expert witness. Clarke cannot point to any evidence but says it seems unlikely he would not have done. He adds that it is likely he advised Fujitsu, Jenkins' employer, that the witness' evidence was compromised. Clarke makes the point that he was not a prosecuting barrister for the Post Office but instead was the barrister who stopped the prosecutions. He was instructed on one prosecution, applied to have it adjourned and stopped the process there.

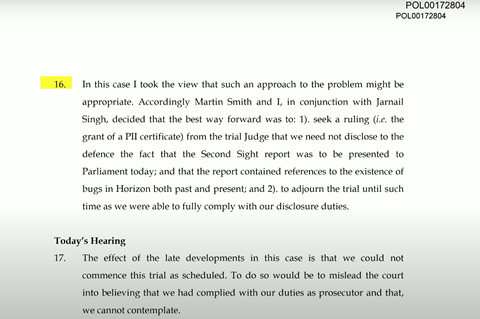

3.35pm: Moloney asks the basis for making the application. Clarke reiterates it was because he believed the report was subject to parliamentary privilege and could not be disclosed. He says it was 'a matter of national interest'.

Moloney points out that parliamentary privilege is not mentioned anywhere in Clarke's attendance notes of the meeting.

Clarke: 'It is not in the document but that does not mean it was not the basis upon which I approached it.'

Moloney: 'I have not suggested that.'

Clarke: 'I think you have.'

'Moloney: 'Why is it not there?'

Clarke: 'A oversight. A mistake. I don't know.'

3.25pm: The inquiry returns with sub-postmasters' representatives given a chance to ask questions. This is often a pinch point in proceedings, with witnesses visibly tired and barristers more confrontational than inquiry counsel. Clarke sits for the first time with his arms crossed and his chin resting on one hand as he is taken by Tim Moloney KC to the public interest immunity application made by Clarke at Birmingham Crown Court (see 10.35am).

Clarke said he was instructed directly to make the PII application and prevent disclosure of the Second Sight report by Post Office solicitors Rodric Williams and Jarnail Singh.

3.05pm: Clarke once again faces accusations he was too worried about adverse press and publicity for the Post Office. In his advice on mediations, he said that this may lead to cases in the Court of Appeal where it was inevitable a 'largely hostile press would attend and report widely on the proceedings'. Clarke says this was a statement of fact and he was seeking to dissuade the Post Office from going ahead with putting criminal cases in the mediation scheme.

Blake points out to Clarke he regularly expressed concerns about press intrusion and asks whether he was 'overly concerned' about this. Clarke says he has used the word 'pandering' and 'I don't resile from that'. Blake finishes his questioning and we go to a break.

3pm: The inquiry sees further advice from 2013 from Clarke regarding the establishment of a mediation scheme, saying that hearing one applicant's case 'may be setting a precedent which others wish to follow, where necessarily they could not'.

In terms of likely appeals from a mediation settlement, Clarke's view was that this would be 'an exercise in futility' as the Court of Appeal would need more proof of innocence. He said this might offer 'false hope' for a sub-postmaster who would launch 'misconceived appeals'. Clarke says he was not aware that the Post Office expressed a view internally that this view was too strongly worded.

2.50pm: More on Clarke's attitude to the Post Office's mediation scheme. He says the Post Office was 'pretending' to offer some help to sub-postmasters and was 'dishonest' about its motivations. 'It was an attempt to keep people quiet,' he adds.

2.45pm: Similar to this morning, Blake takes Clarke to opinions he expressed at the time about other reasons for opposing the mediation scheme.

'We feel bound to point out that the potential for adverse publicity... is inestimable,' he advised in 2013.

Clarke says he was 'fundamentally opposed' in principle to people with criminal convictions being allowed into the mediation scheme but that his concern about adverse was improper.

'I think I went too far,' he tells the inquiry. 'I suppose to a degree we are pandering [to the Post Office concern about publicity].'

2.35pm: Clarke is shown his advice on mediation, where is pretty unequivocal that this should not be undertaken with people who have convictions. This was because he thought the best forum to get redress was firstly in the Court of Appeal. This received 'fierce pushback' from the Justice for Subpostmasters Alliance.

Asked if he would give the same judgement now, he says: 'My view now about trespassing on the Court of Appeal remains but I agreed that what I formulated here is too restrictive. I just thought it was the wrong way round. Secondly I saw it as a way of Post Office keeping [sub-postmasters] quiet and I though that was improper.'

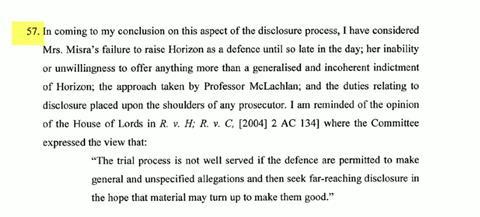

2.20pm: The inquiry sees Clarke advice on the Misra prosecution written in January 2014. In one section, he says that Misra’s conviction was safe as she failed to raise Horizon as a defence until late in the day and offered nothing more than a ‘generalised and incoherent indictment’ of Horizon.

Was his assessment now problematic, asks Blake. Clarke responds: ‘It’s not problematic. It’s wrong.’ He says he was ‘misled and deceived’ on a wide basis.

2.15pm: Back after lunch and no let-up in Clarke's candid responses. The barrister says that the Post Office misled him from the start in his review of the Seema Misra case from 2010, about what was known at the time about Horizon bugs and what was disclosed to her.

'Post Office repeated their protestations that since day dot there was nothing wrong with Horizon when clearly they knew there were issues,' he says.

Asked to name his key contacts at Post Office, he names solicitors Jarnail Singh and Rodric Williams, as well as less frequently general counsels Susan Crichton and Chris Aujard.

12.50pm: Clarke wrote a new draft protocol for the Post Office for its duties as a prosecutor, and he tells the inquiry that the previous policy was wholly inadequate. Clarke believes that previously, John Scott had a say in prosecution decisions.

But Clarke's approach was considered too prescriptive and was rejected in favour of an alternative policy drafted by KC Brian Altman. Clarke tells the inquiry he was 'disappointed' with the Altman approach.

'I rather thought he was watering down some of those hard and fast requirements that should have been there,' says Clarke. 'I wanted the Post Office policy to reflect public policy as set down in the code for crown prosecutors.'We go to the lunch break.

12.40pm: Clarke’s advice ‘sat in a drawer’ for two weeks before Susan Crichton wrote in response: ‘Post Office Limited is committed to conducting its business in an open, transparent and lawful manner. Any suggestion to the contrary would not reflect Post Office Limited policy, and would not be authorised or endorsed by Post Office Limited.’

Clarke says he expected his advice to go to the ‘very highest levels’ of the Post Office for them to deal with John Scott, but he does not know whether it did.

12.35pm: Clarke tells the inquiry he stands by his advice. Blake asks why this was not the last piece of work he did for the Post Office, given how serious the shredding matter was.

Clarke says: 'My understanding was this was not a Post Office policy of instruction. This was John Scott on a frolic of his own.'

Was this a 'maddening situation' that would cause him to end the relationship with Post Office, asks Blake.

'I am just a bit old-fashioned about this. Barristers don't walk away from their clients when life gets difficult. I saw my role as their barrister through Cartwright King who gave palatable and unpalatable advice. It is trite but [I stayed] in the hope I could do some good for them.'

12.30pm: Clarke’s response to Scott’s shredding instruction was unequivocal, advising that the duty to record and return material ‘cannot be abrogated’.

His advice continued: ‘No solicitor, no firm of solicitors and no barrister may be a party to a breach of the duty to record and retain. Neither may they act in circumstances where they are aware, or become aware, that a practice has developed within the investigative or prosecutorial function such that the duty to record and retain is being deliberately flouted, or avoided…. Such a decision, where it is taken partly or wholly in order to avoid future disclosure obligations, may well amount to a conspiracy to pervert the course of justice.’

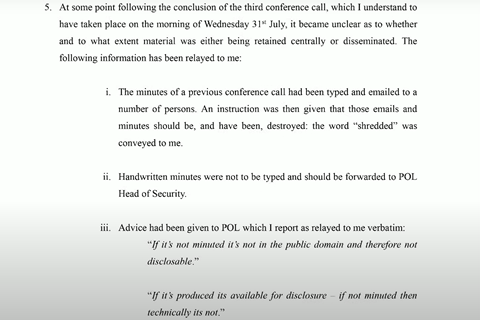

12.20pm: We now go to another big issue: Clarke's note from 2013 that John Scott, the Post Office head of security, had given the instruction to shred minutes of the weekly Horizon meetings.

12pm: Despite Blake's criticisms that Clarke's letter to the CCRC may not have been transparent enough, it was clearly too much for the Post Office executives.

The inquiry sees an internal email from general counsel Susan Crichton discussing Clarke's draft letter, in which she suggests they may need to find alternative advisers.

Clarke is asked if his draft letter was 'too punchy', which he seems find a little bemusing as he was just accused of being too tepid.

'I read the [Crichton] email as Post Office taking the view it was too strong,' he says. 'This looks to me as though they are suggesting they might want to water it down... They clearly didn't like what I had written.'

We go to another quick break.

11.50am: For the first time, Clarke appears to be a little unsettled, offering one-word answers and contradicting the assertions of Blake.

The inquiry counsel takes him to his draft letter to the Criminal Cases Review Commission in 2013 setting out that the Second Sight report had found Gareth Jenkins' evidence was not reliable.

Blake suggests the wording was 'tepid' compared to Clarke's advice directly to the Post Office and that it did not make clear Jenkins knew his evidence was unreliable when he gave it. Clarke says this was not the case and stands by the contents of the letter.

11.40am: Now we're coming onto one of the crucial elements of Clarke's role: his advice in 2013 to the Post Office that Gareth Jenkins was a compromised witness. This passage is highlighted by the inquiry.

11.25am: More candour from Clarke. He says his advice to the Post Office to only review cases after 1 January 2010 was wrong, saying that lawyers 'put the blinkers on' the idea that there might have been Horizon issues before that cut-off date.

The inquiry then hears that Clarke and his colleague Harry Bowyer undertook the 'sift' review of cases, looking themselves at some 76 out of 81. Asked if this process was an independent as it ought to have been, he says: 'I would accept that given the numbers, there might also have been a degree of becoming case-hardened by reviewing so many cases. By the time you get to case 35 it inevitable that human nature tends to dictate you have seen it all before and perhaps you become more cynical.'

11.15am: Clarke is much more willing to admit to his mistakes than other witnesses have been. The inquiry sees copies of the draft and final letters sent to a sub-postmaster in Merthyr Dyfan - the latter seems to water down information about how many other branches are affected by the bug. Clarke had also advised that the existence of the Second Sight did not need to be disclosed in every case.

Blake asks: 'What part of a criminal prosecutor's duty do you see as being concerned with adverse publicity?'

Clarke: 'None'.

Blake: 'So the advice that you gave to the Post Office in respect of this was appropriate or inappropriate?'

Clarke: 'It was ill-judged and inappropriate.'

11.05am: We return by picking up the theme about Clarke's advice on the Post Office stance regarding disclosure of knowledge about bugs.

In an email to Rodric Williams, Clarke queries sending letters disclosing Horizon problems to a select number of sub-postmasters, again mentioning the issue of 'adverse speculation'. Clarke accepts he was worried about speculation at this time but stresses he had limited knowledge about what was happening and wanted to preserve the position until more was known.

10.55am: This really has been a morning session full of interesting submissions and candid responses from Clarke.

Before we go to a break, Blake brings up that Clarke told Post Office solicitor Rodric Williams that Jenkins' evidence was unreliable and he had not disclosed the presence of bugs.

Clarke said he expected shock and horror from Williams, but he appeared to take the information in his stride and start planning for what to do next.

'All I can say is I did not see [from Williams] the surprise and astonishment I expected,' says Clarke.

10.50am: While parliamentary privilege concerns were cited by Clarke as the main factor behind trying to avoid disclosure of the Second Sight report, attendance notes from the time suggest it was not the only reason.

Clarke wrote in 2013 that the Post Office was concerned at the adverse publicity that the report would have generated and that 'to permit this information to enter the public domain at such an early stage would have been to encourage extremely unhealthy and likely virulent speculation as to the content of any report'.

Blake asks Clarke if he accepts whether avoiding adverse publicity was a reason for seeking the court order. Clarke responds: 'I do.'

Was he gloating in this attendance note, asks Blake. 'I hate the word gloating but I think you are probably right.'

10.45am: Clarke reveals that HHJ Chambers was 'quite upset' about the PII application, even though it was granted.

'Effectively we were wasting the court's time by aborting a trial that was due to start that day. The prosecution had plainly not done that which they ought to have done in time for the trial.'

Asked by Blake if the application was appropriate, looking back now, Clarke says: 'I would go as far as to say if I were in the same situation now with the same information I had I would make that application again.'

10.40am: Clarke explains there was nothing improper about the application and his attendance note (see below) states that it was made because Cartwright King was concerned that disclosing the Second Sight report might have been a breach of parliamentary privilege, as it was due to be shown to MPs that week. He also denies that defence solicitors would not have been told about the meeting with the judge in his chambers.

'It is common practice amongst counsel that if a PII application is to be made the defending counsel will be informed informally at court by prosecuting counsel and that is what I did.

'The proposition I could just go and see the judge without telling defence counsel would at the very least have prompted defence counsel to say "what is going on". Defence counsel would have had to be informed and he was.'

10.35am: The inquiry is going through Clarke’s attendance note in relation to the prosecution of Balvinder Samra at Birmingham Crown Court. This trial was adjourned for eight weeks by His Honour Judge Chambers after Clarke and Smith made a successful application for public interest immunity, preventing the defence from being told about the existence of the Second Sight draft report. This was covered in detail at Martin’s Smith inquiry evidence session.

10.25am: Inquiry sees an excerpt from Clarke's witness statement (below), where he says Post Office's attitude to disclosing details of Horizon problems amounted to an 'article of faith' and an 'almost religious panic'.

10.20am: The inquiry sees a transcript of a telephone conversation with Gareth Jenkins, secretly recorded by Clarke and Smith. Clarke says it came as a 'bombshell' to find out that Jenkins had admitted the presence of bugs in Horizon and that he had not disclosed this in criminal trials.

'I thought it was hugely important we knew who told Second Sight of the bugs,' he says. 'If it had been Fujitsu or Gareth Jenkins then frankly Gareth Jenkins was in trouble.'

10.15am: Clarke says that finding out there were bugs in Horizon, as was about to be reported by Second Sight, should have been a decisive moment, describing it as a 'process stopping mechanism'.'You can't go anywhere from that other than to say who? how? why? who told them?,' he says. 'Because your duties as a prosecutor are so absolute in those circumstances that any competent barrister is going to say "well stop, we have to see what is going on".'

10.05am: Clarke is asked whether part of the problem with Post Office was that people worked in silos. 'One of the reasons why these two Horizon bugs detected by [forensic accountants] Second Sight escaped people's attention was because nobody was talking to each other. As simple as that... I was encountering it in June, July, August of 2013. I put it down to office politics. People were working within their own comfort zones and never the twain shall meet.'

9.55am: Clarke's former colleague at Cartwright King, Martin Smith, said last week that he deferred to him. Clarke denies that was the case. The barrister also says he was 'surprised' to see in Smith's evidence session that he would liaise with Post Office off his own back. Smith had also said he had shortcomings in his knowledge, which Clarke appears to deny.

The dynamic is interesting partly because Clarke and Smith left Cartwright King together and set up their own firm.

9.50am: Clarke confirms he joined Cartwright King in 2010 and advised the Post Office on prosecutions but was not responsible for the decision on whether to prosecute.

Asked by inquiry counsel Julian Blake whether he had autonomy, he says he occasionally saw something that concerned him and advised the Post Office of this. Sometimes the Post Office was resistant to advice, sometimes they accepted it.

No comments yet