The cases of Andrew Malkinson and Winston Trew have stoked concerns that majority verdicts increase the chances of a wrongful conviction. Now APPEAL is calling for jury unanimity to be reinstated

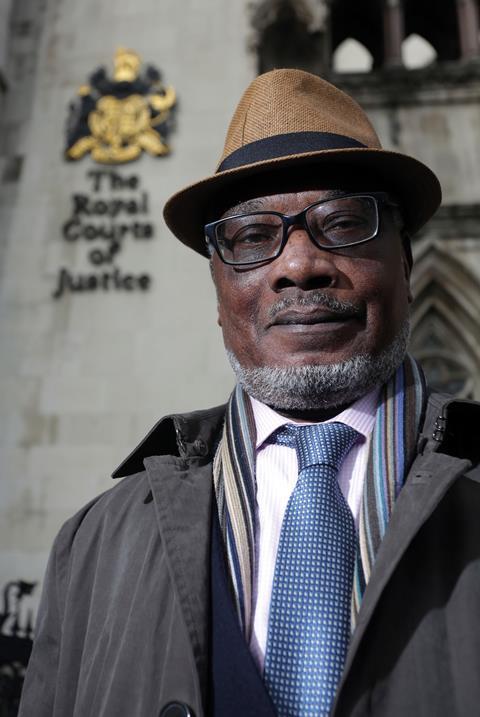

Andrew Malkinson, who spent 17 years in prison for a rape he did not commit, and Winston Trew, who was convicted in 1972 of attempted theft and assault, both appear on the cover of APPEAL’s report Doubt Dismissed: Race, Juries and Wrongful Conviction.

Their convictions have since been overturned, but Malkinson and Trew have something else in common. They were wrongfully convicted on a 10/2 majority verdict.

The campaign body’s report explores why a centuries-old jury system that required juries to reach a collective agreement was replaced in 1967 with a system that allowed majority verdicts. Authors Nisha Waller, APPEAL’s racial justice lead, and solicitor Naima Sakande, a former APPEAL deputy director, conclude that, against a backdrop of tumultuous race relations in 1960s Britain, and a swift expansion of juror eligibility to include more working class and negatively racialised people, concerns about newly diverse juries’ ability to render just decisions were both classist and racist.

The report was discussed at a Legal Action Group event at London’s Garden Court Chambers on Tuesday. Waller said: ‘If the jury were required to convict unanimously, it is possible that Andrew Malkinson might not have spent 17 years in prison or Winston Trew half a century fighting to overturn his conviction.’

This article is now closed for comment.

The Contempt of Court Act 1981 made the authors’ efforts to assess the implications challenging. Section 8 criminalises obtaining, disclosing or soliciting any statements made, opinions expressed, arguments advanced or votes cast by members of a jury during their deliberations in any legal proceedings.

Waller said: ‘The jury system in England and Wales is the most secret part of the criminal justice system. I can go and do research in any other institution of the criminal justice system – the police, Crown Prosecution Service, judiciary, prisons. But I cannot apply to do research with real jurors in real cases, so little is known about how juries came to their decision, and how race, class and gender influence their decisions.’

The report identifies 56 people who were wrongfully convicted by a majority verdict and had their convictions quashed. The authors ‘strongly believe there are more’, the event heard.

‘Do majority verdicts increase the chances of wrongful conviction? Whose voices are being excluded by majority verdicts?’ Waller asked. ‘Juries are the black box very rarely opened. If our aim is to strengthen the jury system, we can only do so if we scrutinise it.’

The report cites a rape trial at Birmingham Crown Court overshadowed by the discharge of juror 12, who expressed concerns to the judge about racial bias on the jury. The remaining 11 jurors reached a unanimous guilty verdict. Waller told the event the case demonstrates how easy it is for the voices of jurors to be sidelined. ‘We cannot uphold the integrity of the jury system if it is completely opaque and exempt from scrutiny. Majority verdicts provide an obvious gateway for exclusion of dissenting voices.’

The report concludes that:

- the principle of jury unanimity to be reinstated.

- Section 8 of the Contempt of Court Act should be amended to allow official research of jury deliberations by academic institutions or government agencies – a proposal that echoes the Law Commission’s recommendation in its 2013 report, Contempt of Court: Juror Misconduct and Internet Publications.

- Crown court data should be improved.

APPEAL’s report says data is currently only collected on convictions. To understand patterns of bias in majority decisions, data should be gathered on the ethnicity of dissenting minority jurors and assenting majority jurors. These would not be declared in open court. Anonymous juror surveys should be conducted and recorded after every case.

What happens now? ‘We’re not planning to leave this report sitting there and not take action,’ Waller said. The next step is discussions with the Ministry of Justice to see if the department is willing to ensure the necessary data is collected.

The event heard there is a potential legal case under the Public Sector Equality Duty which could force the government to collect this data. APPEAL hopes such a prompt will not be necessary. APPEAL wants the report to be the first step toward better data gathering and analysis on majority verdicts, and further critical inquiry into the relationship between Britain’s colonial history, racism, classism and the jury system. ‘Justice need not silence or sideline,’ the report concludes.

20 Readers' comments