The recent decision of DSN v Blackpool Football Club Limited [2020] EWHC 670 (QB) illustrates the need for litigating parties to consider and engage with alternative dispute resolution (ADR) procedures in trying to resolve their disputes.

Facts

The claimant was successful in his claim for damages against the defendant for vicarious liability in respect of sexual abuse carried out by a previous employee of the defendant. However, the parties were unable to agree on a number of consequential issues, including whether costs should be on the standard or indemnity basis.

The claimant argued that the defendant should pay its costs on an indemnity basis because it had failed to engage in settlement discussions. The case management direction dealing with ADR stated: (i) the parties should consider settling their dispute through ADR; (ii) witness statements should be filed by any party who has failed to engage with ADR; (iii) the witness statement should be disclosed after trial and when the court considers the issue of costs.

The defendant refused to engage in settlement negotiations with the claimant on the grounds that it was ‘confident in the strength of its defence’. Pursuant to the case management directions, the defendant filed a statement indicating that it had refused to engage in ADR because, after considering all of the evidence in the case, it continued to believe that it had ‘a strong defence to this claim and stands by the content of its defence’. The defendant also rejected the claimant’s various Part 36 offers.

Judgment

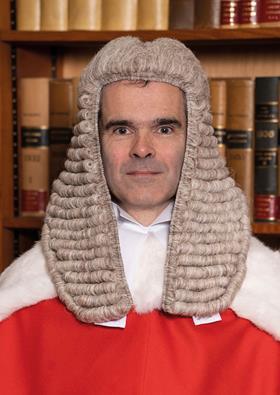

The judge, Mr Justice Griffiths (pictured), found that the reasons given by the defendant for refusing to engage with ADR were inadequate and that ‘no defence, however strong, by itself justifies a failure to engage in any kind of alternative dispute resolution’. The judge explained the practical virtues offered by ADR procedures over the court process when he stated that: ‘Settlement allows solutions which are potentially limitless in their ingenuity and flexibility, and they do not necessarily require any admission of liability, or even a payment of money.’ Even if money is paid, that amount may compare favourably with the irrecoverable costs of an action that has been successfully fought. The judge also stated that trials typically involve a significant expenditure of time and costs, and take a toll on the witnesses even for successful parties which a settlement could avoid. Further, a settlement could include statements that fall short of accepting legal liability, which may still be of value for the claimant.

The claimant had not, the judge noted, primarily been motivated by money and wanted to engage with the defendant to understand what had happened. But the defendant chose not to engage. The judge found that the defendant did not have a strong defence; in fact, it lost the case. Although that in itself did not justify an award of indemnity costs, the conduct of the defendant took the case ‘out of the norm’ (per Lord Woolf in Excelsior Commercial & Industrial Holdings Ltd v Salisbury Hamer Aspden & Johnston (Costs) [2002] EWCA Civ 879) and the response to the master’s directions was ‘particularly disappointing’ (Dunnett v Railtrack plc [2002] EWCA Civ 303). Although the judge refused to make an indemnity order for the whole of the proceedings, he ordered that the defendant pay the claimant’s costs on an indemnity basis from one month after the date of the master’s case management order.

The decision reinforces the important role played by ADR within the civil justice system, and illustrates judicial expectations that the parties must comply with their ADR obligations, or the courts will not hesitate to penalise defaulting parties in costs.

The decision is also consistent with previous ADR authorities, in particular PGF v OMFS [2013] EWCA Civ 1288 and Thakkar v Patel [2017] EWCA Civ 117, which make clear that it is not enough for a party to decline to engage with ADR simply because it believes that it has a strong defence or claim.

Finally, the decision provides a useful reminder of some of the economic and practical benefits available to the parties if they positively engage with ADR which are not available through the civil court process.

Masood Ahmed is an associate professor at the University of Leicester and a member of the Civil Procedure Rule Committee

No comments yet