Protectionism is back and the world’s rules-based system of trade and dispute settlement is coming under severe stress. Marialuisa Taddia reports.

THE LOW DOWN

The UK has its work cut out as it seeks to return to the World Trade Organization as a separate party from the EU, which will likely involve negotiations with the WTO’s 164 members. But as with the EU on Brexit, establishing the status of the UK is one item on a much longer list.

The US is one of several countries testing the resilience of the WTO via GATT Article XXI, which allows an exemption from its rules on national security grounds. Meanwhile, a crisis in the appointment of judges to the Appellate Body, the WTO’s highest court, is threatening to undermine the trade body’s dispute settlement system, described as its ‘jewel in the crown’, and ultimately the WTO itself.

As if the stakes were not high enough, the WTO’s key role in tackling climate change makes it one of the bodies the world is relying on to avert environmental catastrophe.

From Brexit and the role of the World Trade Organization in tackling climate change, to the threat to the existence of the WTO’s highest court and the global trade war waged by the US – there was no shortage of hard topics at 2018’s WTO conference in June.

Organised by the British Institute for International and Comparative Law (BIICL), the event, launched in 2000, was originally held in May to coincide with the annual visit to London of the late professor John Jackson, regarded as the founding father of international trade law. Opening the conference, professor Sir Francis Jacobs of King’s College noted: ‘Professor Jackson would be intrigued by the divisions which Brexit has provoked in the UK, [and] perhaps bemused by what has befallen the British political system, well-known, I think, in the past for its degree of stability and maturity.’

The UK has its work cut out when it comes to international trade relations. This was clear from the first panel, which tackled such tricky issues as the UK’s WTO membership outside the EU, and the rollover of the EU’s free-trade agreements (FTAs).

Dr Lorand Bartels, senior counsel at Linklaters, referred to ‘Lampedusa’s Brexit’. He was echoing recent comments by a senior EU official who, paraphrasing The Leopard by Tomasi di Lampedusa, said he had the impression ‘the UK thinks everything has to change on the EU’s side so that everything can stay the same for the UK’.

The EU has 40 trade agreements with 70 countries. A top priority is to ensure the UK continues to benefit from those agreements beyond the transition period, by rolling them over or ‘grandfathering’ them.

At the time of writing, if the terms of the UK and EU’s draft agreement on withdrawal remain unchanged, then the transition period will run from 29 March 2019 to the end of 2020. During that time the UK will be bound by the obligations stemming from the international agreements concluded by the union, article 124(1) of the draft Withdrawal Agreement says. There is an important footnote: ‘The union will notify the other parties to these agreements that during the transition period, the United Kingdom is to be treated as a member state for the purposes of these agreements.’ It will provide a level of certainty and continuity.

The UK is a founding member of the WTO, which was created 1995, and was one of the first signatories to its predecessor – the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade.

Within the WTO, one conference speaker noted, the UK ‘acts under the umbrella of the EU, and needs to come out of it and regain an independent seat’. On exit, the UK will also need its own ‘schedules’ (which it now shares with the EU) setting out detailed WTO commitments on tariffs and trade barriers.

‘Some have said that it is a simple matter of rectification. In reality a renegotiation is necessary,’ Eric White, a consultant at Herbert Smith Freehills in Brussels, explained. ‘This probably cannot be finalised until the EU-UK relationship is agreed.’

White pointed to the first public evidence of any attempt by the EU and the UK to split current tariff rate quotas (TRQs) – relating to imports of agricultural products such as meat, sugar and grains. In a joint letter to the WTO membership in October 2017, they pledged to ‘maintain existing levels of market access available to other WTO members’ with the proposals to apportion TRQs, based on historical imports and patterns of consumption.

This proposal was immediately rejected by seven major agricultural exporters, including the US, Argentina, Brazil and New Zealand, whose consent to the changes will be required. The European Commission has since suggested another route. According to White, it is seeking a negotiation mandate from the council, but only for the apportionment of TRQs, and not for other adjustments such as agricultural subsidy limits and services. It also proposes that the EU authorise the UK to negotiate its own schedules of commitments, not limited to TRQs.

In what he described as ‘the law of the jungle in trade negotiations’, White said a ‘cooperative approach’ between the EU and UK was ‘essential – otherwise the EU and the UK will both end up paying trade compensation to other WTO members and also FTA partners’.

Speaking in a personal capacity, Gabrielle Marceau, senior counsellor in the legal affairs division of the WTO, pointed out that the basic principle of the WTO is non-discrimination, with regional trade agreements the exception. Tariffs at levels under ‘maximum bindings’ (commitments not to increase rate of duty beyond an agreed level) are applied equally on imports from all trading partners through the ‘most-favoured nation treatment’ (MFN) to ensure the smooth flow of trade in goods. The same applies to MFN TRQs. A WTO member may propose changes to TRQs, but if this adversely affects market access rights of other WTO members, there will be requests for compensation.

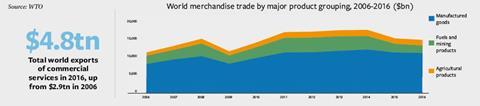

It is not surprising that, for an organisation with 164 members representing 98% of world trade, Brexit is just one of myriad issues affecting the WTO. Near the top of that list is the role the WTO and trade law could play in achieving the goals of the Paris Agreement, the climate accord within the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change starting in 2020.

Conference organiser Dr Markus Gehring, Arthur Watts senior research fellow in public international law at BIICL, pointed out that countries are making greater use of regional trade agreements (RTAs) to try to achieve environment and climate goals. Take the newly adopted EU-Singapore RTA, which contains an ‘entire chapter on facilitating renewable energy production’.

‘DISINTEGRATION OF THE CONSTITUTIONAL GLUE’

The WTO’s General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), which allows an exemption from its rules for national security (Article XXI), has seldom been used as a defence in WTO disputes (and the WTO has never had to rule on it). But it has ‘emerged from obscurity’ in the past year, according to Markus Wagner, associate professor of law at Warwick University.

Russia has invoked Article XXI(b)(iii) in the ongoing Russia – Traffic in Transit (DS512) dispute, which relates to a complaint by Ukraine over alleged multiple restrictions on traffic in transit from Ukraine through the Russian Federation to third countries. The United Arab Emirates, Saudi Arabia, Egypt and Bahrain are also relying on Article XXI to justify the land, sea and air embargo on Qatar in response to its alleged funding of terrorist organisations.

The US, which introduced import tariffs of 25% on steel and 10% on aluminium on 1 June, is justifying its decision on grounds of ‘national security’, and is widely expected to invoke GATT Article XXI in its defence. On the same day, the EU (and other countries) launched proceedings against the US in the WTO. Wagner emphasised the ‘systemic importance’ of Article XXI – if invoking it became normal practice it would lead to the ‘disintegration of the constitutional glue’ of the WTO as no country would be bound by its rules.

At the time of writing, draft legislation from the Trump administration was in circulation that would remove the legal alignment of US law with WTO principles, though its effect if made law is uncertain.

Diane Desierto, professor of human rights law and global affairs at the University of Notre Dame, mentions Sweden, which in 1975 argued that Swedish leather and plastic shoe quotas were necessary to maintain minimum domestic production capacity, in order to secure provision of essential products in time of war or other emergencies. Many states objected at the GATT Council. Sweden relented in 1977.

Gehring also highlighted the importance of reforming fisheries subsidies in the WTO. Negotiations were launched at the ministerial conference in Doha in 2001. At last year’s Buenos Aires ministerial meeting government members decided to work towards a ‘comprehensive’ agreement on fisheries subsidies by 2019. This would fulfil a ‘multilateral commitment’ to prohibit and eliminate, by 2020, fisheries subsidies that contribute to illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing.

‘Successful fisheries subsidies reform will directly contribute to the implementation of the Paris Agreement and to the delivery of [the UN’s] Sustainable Development Goal 13 on climate change, given the important synergies that exist between the transformation of fisheries subsidies and climate mitigation and adaptation,’ Gehring said. ‘Furthermore, fisheries subsidies negotiations are crucial for international climate law’ because ‘they can provide a case study to learn from and increase chances of success with fossil fuel subsidy reform.’

Dr Damilola Olawuyi, associate professor at the College of Law and Public Policy in Doha, Qatar, focused on the Middle East and its near-dependence on energy subsidies (the region accounts for about half of global energy subsidies). Through them ‘rentier states provide social protection and share hydrocarbon wealth’, Olawuyi explained. In Qatar, for example, electricity is free for domestic use – yet the country aims to generate 20% of its electricity from solar systems and ‘achieve a diversified economy that gradually reduces dependence on hydrocarbon industries’ by 2030.

A number of Middle East countries have pledged to reform their energy subsidy systems, Olawuyi noted, but ‘this is likely to be gradual, given the politically sensitive nature of subsidies in rentier states of the Middle East’.

The WTO, especially via the Agreement on Subsidies and Countervailing Measures (SCM) and its Trade Policy Review Mechanism, ‘offers a multilateral framework for clarifying and addressing the impacts of energy subsidies on climate action’, according to Olawuyi. The SCM agreement could be ‘enhanced’, for example, by expanding categories of prohibited subsidies beyond commercial sectors; and promoting ‘regional and triangular’ cooperation on the reform of subsidies, Olawuyi concluded.

Trade disputes crisis

Arguably the biggest challenge yet is to the jewel in the crown of the WTO – its dispute settlement mechanism, and in particular the Appellate Body (AB), which hears appeals from reports issued by panels in disputes brought by WTO members. Two-thirds of all panel reports are appealed.

The AB is composed of seven permanent members who are appointed by the Dispute Settlement Body (DSB) to serve for a four-year term (they can be reappointed once for another four years). The DSB comprises representatives of all 164 WTO members, and appointments to the AB must be unanimously agreed (decisions are taken by ‘consensus’ and a formal objection by any member state can block the appointment or reappointment of an AB member).

Hence the problem – the AB is currently down to four members because the US is blocking the process for the replacement of judges whose terms have ended. With another member due to leave at the end of September (and two at the end of December next year) the prospects are ‘bleak’ since each case requires at least three sitting members. As one speaker said: ‘The AB is teetering on the edge of a precipice.’

Although the crisis has deepened under the current US administration, ‘there have been longstanding tensions within the WTO about the functioning of the AB, cutting across at least three US administrations’, said Christophe Bondy, special counsel in the London office of Cooley LLP.

The AB, which came into being in 1995, ‘has reinforced the WTO’s institutional ability to interpret the agreements of the members in an authoritative, quasi-judicial manner’, according to Bondy. But, he added, that is another source of concern for the US, which ‘generally condemns the so-called “judicial activism” of AB judges. It has criticised panels and the AB for overreaching their authority by allegedly filling gaps, construing silences, selectively choosing definitions, and creating obligations not agreed by members’.

While previous administrations raised such complaints and blocked the appointment or reappointment of certain judges on these grounds, the current US administration has taken things a step further, effectively blocking all new appointments or reappointments. The result has been an AB starved of new members. The AB is on the point of grinding to a halt for lack of decision-makers.

Bondy pointed to the farewell speech of AB member Ricardo Ramírez-Hernández at the end of May as a summary of the issues WTO members need to consider if they want to reform and save the body. Ramirez focused on the way forward for the AB, rather than engaging in ‘US-bashing or teeth-gnashing’, Bondy said. But Ramírez-Hernández affirmed that the AB did not deserve to be condemned by ‘asphyxiation’. Bondy concluded by querying whether WTO members remained committed to a system of independent and impartial decision-making, as opposed to resolving disputes through negotiation and the exercise of members’ economic power. The former approach is needed if the WTO is to continue contributing to the international rule of law.

Mary Footer, professor of international economic law at the University of Nottingham, recalled another ‘empty chair crisis’, which led to the ‘Luxembourg compromise’ in January 1966, as ‘a lesson for the ongoing WTO crisis’. On 1 July 1965, French president Charles de Gaulle withdrew the French permanent representative from the Council of Ministers in Brussels in protest against the abolition of unanimous voting in agricultural and budgetary issues under the Treaty of Rome 1957. This caused a six-month deadlock within the European Economic Community.

The Luxemburg compromise in 1966 broke the impasse – if a country believed that its vital national interests might be adversely affected, negotiations had to continue until a universally acceptable compromise was reached. The compromise was a political fix, rather than an ‘institutional solution’, Footer observed. A solution only came with the Single European Act 1987, which reformed the EU voting system by allowing the council to take decisions by qualified majority.

Melbourne Law School professor Andrew Mitchell pondered some of the available options for ‘breaking the deadlock’, including amending the AB’s working procedures and selecting AB members by majority voting in either the General Council or the DSB. But both options risked ‘alienating the US in the context of WTO dispute settlement, and potentially contributing to its further disengagement from the WTO as a whole’, Mitchell argued.

Mitchell’s preferred option would be to set up a ‘temporary appeal procedure based on existing, but largely unused, right to bilateral arbitration under Article 25 of the Dispute Settlement Understanding’. The DSU, which is part of the WTO trade rules, sets out the procedures and rules of the organisation’s dispute settlement system.

One main benefit of this approach is that it would use rules in the WTO agreements themselves (instead of the working procedures), ‘hence not enhancing the existing US concerns about going beyond the treaty’, Mitchell said. But it would ‘add to the time and costs of disputes in an already clogged dispute resolution system’.

Yet the difficulties facing the WTO’s dispute settlement system are not an anomaly. ‘International courts… are being increasingly scrutinised by states in response to unwelcome rulings,’ Mitchell added, pointing to: Croatia’s rejection of the Croatia-Slovenia arbitration award rendered in 2017 in favour of Slovenia; China’s rejection of the South China Sea arbitration award issued in 2016 in favour of the Philippines; and ‘attacks on the credibility of the European Court of Human Rights and the International Criminal Court’.

The way forward has to be assessed in this context. As Mitchell concluded: ‘Temporary fixes to address only the symptoms and not the cause of the AB blockage do not lend themselves to creating a stable and consistent ecosystem for dispute settlement at the WTO.’

Marialuisa Taddia is a freelance journalist

No comments yet